Regular readers know I have a long-standing interest in memristor and artificial brains. I have three memristor-related pieces of research, published in the last month or so, for this post.

First, there’s some research into nano memory at RMIT University, Australia, and the University of California at Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara). From a May 12, 2015 news item on ScienceDaily,

RMIT University researchers have mimicked the way the human brain processes information with the development of an electronic long-term memory cell.

Researchers at the MicroNano Research Facility (MNRF) have built the one of the world’s first electronic multi-state memory cell which mirrors the brain’s ability to simultaneously process and store multiple strands of information.

The development brings them closer to imitating key electronic aspects of the human brain — a vital step towards creating a bionic brain — which could help unlock successful treatments for common neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

A May 11, 2015 RMIT University news release, which originated the news item, reveals more about the researchers’ excitement and about the research,

“This is the closest we have come to creating a brain-like system with memory that learns and stores analog information and is quick at retrieving this stored information,” Dr Sharath said.

“The human brain is an extremely complex analog computer… its evolution is based on its previous experiences, and up until now this functionality has not been able to be adequately reproduced with digital technology.”

The ability to create highly dense and ultra-fast analog memory cells paves the way for imitating highly sophisticated biological neural networks, he said.

The research builds on RMIT’s previous discovery where ultra-fast nano-scale memories were developed using a functional oxide material in the form of an ultra-thin film – 10,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Dr Hussein Nili, lead author of the study, said: “This new discovery is significant as it allows the multi-state cell to store and process information in the very same way that the brain does.

“Think of an old camera which could only take pictures in black and white. The same analogy applies here, rather than just black and white memories we now have memories in full color with shade, light and texture, it is a major step.”

While these new devices are able to store much more information than conventional digital memories (which store just 0s and 1s), it is their brain-like ability to remember and retain previous information that is exciting.

“We have now introduced controlled faults or defects in the oxide material along with the addition of metallic atoms, which unleashes the full potential of the ‘memristive’ effect – where the memory element’s behaviour is dependent on its past experiences,” Dr Nili said.

Nano-scale memories are precursors to the storage components of the complex artificial intelligence network needed to develop a bionic brain.

Dr Nili said the research had myriad practical applications including the potential for scientists to replicate the human brain outside of the body.

“If you could replicate a brain outside the body, it would minimise ethical issues involved in treating and experimenting on the brain which can lead to better understanding of neurological conditions,” Dr Nili said.

The research, supported by the Australian Research Council, was conducted in collaboration with the University of California Santa Barbara.

Here’s a link to and a citation for this memristive nano device,

Donor-Induced Performance Tuning of Amorphous SrTiO3 Memristive Nanodevices: Multistate Resistive Switching and Mechanical Tunability by Hussein Nili, Sumeet Walia, Ahmad Esmaielzadeh Kandjani, Rajesh Ramanathan, Philipp Gutruf, Taimur Ahmed, Sivacarendran Balendhran, Vipul Bansal, Dmitri B. Strukov, Omid Kavehei, Madhu Bhaskaran, and Sharath Sriram. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201501019 Article first published online: 14 APR 2015

© 2015 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This paper is behind a paywall.

The second published piece of memristor-related research comes from a UC Santa Barbara and Stony Brook University (New York state) team but is being publicized by UC Santa Barbara. From a May 11, 2015 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

In what marks a significant step forward for artificial intelligence, researchers at UC Santa Barbara have demonstrated the functionality of a simple artificial neural circuit (Nature, “Training and operation of an integrated neuromorphic network based on metal-oxide memristors”). For the first time, a circuit of about 100 artificial synapses was proved to perform a simple version of a typical human task: image classification.

A May 11, 2015 UC Santa Barbara news release (also on EurekAlert)by Sonia Fernandez, which originated the news item, situates this development within the ‘artificial brain’ effort while describing it in more detail (Note: A link has been removed),

“It’s a small, but important step,” said Dmitri Strukov, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. With time and further progress, the circuitry may eventually be expanded and scaled to approach something like the human brain’s, which has 1015 (one quadrillion) synaptic connections.

For all its errors and potential for faultiness, the human brain remains a model of computational power and efficiency for engineers like Strukov and his colleagues, Mirko Prezioso, Farnood Merrikh-Bayat, Brian Hoskins and Gina Adam. That’s because the brain can accomplish certain functions in a fraction of a second what computers would require far more time and energy to perform.

… As you read this, your brain is making countless split-second decisions about the letters and symbols you see, classifying their shapes and relative positions to each other and deriving different levels of meaning through many channels of context, in as little time as it takes you to scan over this print. Change the font, or even the orientation of the letters, and it’s likely you would still be able to read this and derive the same meaning.

In the researchers’ demonstration, the circuit implementing the rudimentary artificial neural network was able to successfully classify three letters (“z”, “v” and “n”) by their images, each letter stylized in different ways or saturated with “noise”. In a process similar to how we humans pick our friends out from a crowd, or find the right key from a ring of similar keys, the simple neural circuitry was able to correctly classify the simple images.

“While the circuit was very small compared to practical networks, it is big enough to prove the concept of practicality,” said Merrikh-Bayat. According to Gina Adam, as interest grows in the technology, so will research momentum.

“And, as more solutions to the technological challenges are proposed the technology will be able to make it to the market sooner,” she said.

Key to this technology is the memristor (a combination of “memory” and “resistor”), an electronic component whose resistance changes depending on the direction of the flow of the electrical charge. Unlike conventional transistors, which rely on the drift and diffusion of electrons and their holes through semiconducting material, memristor operation is based on ionic movement, similar to the way human neural cells generate neural electrical signals.

“The memory state is stored as a specific concentration profile of defects that can be moved back and forth within the memristor,” said Strukov. The ionic memory mechanism brings several advantages over purely electron-based memories, which makes it very attractive for artificial neural network implementation, he added.

“For example, many different configurations of ionic profiles result in a continuum of memory states and hence analog memory functionality,” he said. “Ions are also much heavier than electrons and do not tunnel easily, which permits aggressive scaling of memristors without sacrificing analog properties.”

This is where analog memory trumps digital memory: In order to create the same human brain-type functionality with conventional technology, the resulting device would have to be enormous — loaded with multitudes of transistors that would require far more energy.

“Classical computers will always find an ineluctable limit to efficient brain-like computation in their very architecture,” said lead researcher Prezioso. “This memristor-based technology relies on a completely different way inspired by biological brain to carry on computation.”

To be able to approach functionality of the human brain, however, many more memristors would be required to build more complex neural networks to do the same kinds of things we can do with barely any effort and energy, such as identify different versions of the same thing or infer the presence or identity of an object not based on the object itself but on other things in a scene.

Potential applications already exist for this emerging technology, such as medical imaging, the improvement of navigation systems or even for searches based on images rather than on text. The energy-efficient compact circuitry the researchers are striving to create would also go a long way toward creating the kind of high-performance computers and memory storage devices users will continue to seek long after the proliferation of digital transistors predicted by Moore’s Law becomes too unwieldy for conventional electronics.

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Training and operation of an integrated neuromorphic network based on metal-oxide memristors by M. Prezioso, F. Merrikh-Bayat, B. D. Hoskins, G. C. Adam, K. K. Likharev, & D. B. Strukov. Nature 521, 61–64 (07 May 2015) doi:10.1038/nature14441

This paper is behind a paywall but a free preview is available through ReadCube Access.

The third and last piece of research, which is from Rice University, hasn’t received any publicity yet, unusual given Rice’s very active communications/media department. Here’s a link to and a citation for their memristor paper,

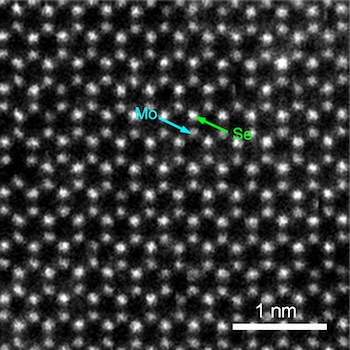

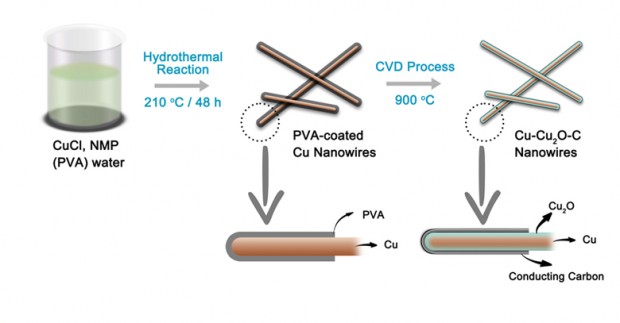

2D materials: Memristor goes two-dimensional by Jiangtan Yuan & Jun Lou. Nature Nanotechnology 10, 389–390 (2015) doi:10.1038/nnano.2015.94 Published online 07 May 2015

This paper is behind a paywall but a free preview is available through ReadCube Access.

Dexter Johnson has written up the RMIT research (his May 14, 2015 post on the Nanoclast blog on the IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website). He linked it to research from Mark Hersam’s team at Northwestern University (my April 10, 2015 posting) on creating a three-terminal memristor enabling its use in complex electronics systems. Dexter strongly hints in his headline that these developments could lead to bionic brains.

For those who’d like more memristor information, this June 26, 2014 posting which brings together some developments at the University of Michigan and information about developments in the industrial sector is my suggestion for a starting point. Also, you may want to check out my material on HP Labs, especially prominent in the story due to the company’s 2008 ‘discovery’ of the memristor, described on a page in my Nanotech Mysteries wiki, and the controversy triggered by the company’s terminology (there’s more about the controversy in my April 7, 2010 interview with Forrest H Bennett III).