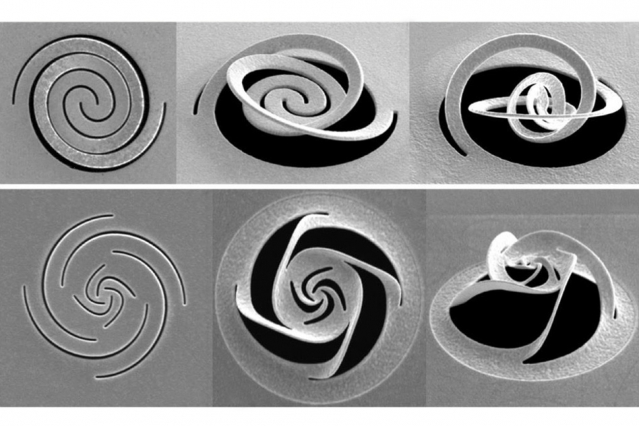

At left, different patterns of slices through a thin metal foil, are made by a focused ion beam. These patterns cause the metal to fold up into predetermined shapes, which can be used for such purposes as modifying a beam of light. Courtesy of the researchers

Nanokiragami (or nano-kiragami) is a fully fledged field of research? That was news to me as was much else in a July 6, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

Nanokirigami has taken off as a field of research in the last few years; the approach is based on the ancient arts of origami (making 3-D shapes by folding paper) and kirigami (which allows cutting as well as folding) but applied to flat materials at the nanoscale, measured in billionths of a meter.

Now, researchers at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and in China have for the first time applied this approach to the creation of nanodevices to manipulate light, potentially opening up new possibilities for research and, ultimately, the creation of new light-based communications, detection, or computational devices.

A July 6, 2018 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, adds detail,

The findings are described today [July 6, 2018] in the journal Science Advances, in a paper by MIT professor of mechanical engineering Nicholas X Fang and five others. Using methods based on standard microchip manufacturing technology, Fang and his team used a focused ion beam to make a precise pattern of slits in a metal foil just a few tens of nanometers thick. The process causes the foil to bend and twist itself into a complex three-dimensional shape capable of selectively filtering out light with a particular polarization.

Previous attempts to create functional kirigami devices have used more complicated fabrication methods that require a series of folding steps and have been primarily aimed at mechanical rather than optical functions, Fang says. The new nanodevices, by contrast, can be formed in a single folding step and could be used to perform a number of different optical functions.

For these initial proof-of-concept devices, the team produced a nanomechanical equivalent of specialized dichroic filters that can filter out circularly polarized light that is either “right-handed” or “left-handed.” To do so, they created a pattern just a few hundred nanometers across in the thin metal foil; the result resembles pinwheel blades, with a twist in one direction that selects the corresponding twist of light.

The twisting and bending of the foil happens because of stresses introduced by the same ion beam that slices through the metal. When using ion beams with low dosages, many vacancies are created, and some of the ions end up lodged in the crystal lattice of the metal, pushing the lattice out of shape and creating strong stresses that induce the bending.

“We cut the material with an ion beam instead of scissors, by writing the focused ion beam across this metal sheet with a prescribed pattern,” Fang says. “So you end up with this metal ribbon that is wrinkling up” in the precisely planned pattern.

“It’s a very nice connection of the two fields, mechanics and optics,” Fang says. The team used helical patterns to separate out the clockwise and counterclockwise polarized portions of a light beam, which may represent “a brand new direction” for nanokirigami research, he says.

The technique is straightforward enough that, with the equations the team developed, researchers should now be able to calculate backward from a desired set of optical characteristics and produce the needed pattern of slits and folds to produce just that effect, Fang says.

“It allows a prediction based on optical functionalities” to create patterns that achieve the desired result, he adds. “Previously, people were always trying to cut by intuition” to create kirigami patterns for a particular desired outcome.

The research is still at an early stage, Fang points out, so more research will be needed on possible applications. But these devices are orders of magnitude smaller than conventional counterparts that perform the same optical functions, so these advances could lead to more complex optical chips for sensing, computation, or communications systems or biomedical devices, the team says.

For example, Fang says, devices to measure glucose levels often use measurements of light polarity, because glucose molecules exist in both right- and left-handed forms which interact differently with light. “When you pass light through the solution, you can see the concentration of one version of the molecule, as opposed to the mixture of both,” Fang explains, and this method could allow for much smaller, more efficient detectors.

Circular polarization is also a method used to allow multiple laser beams to travel through a fiber-optic cable without interfering with each other. “People have been looking for such a system for laser optical communications systems” to separate the beams in devices called optical isolaters, Fang says. “We have shown that it’s possible to make them in nanometer sizes.”

The team also included MIT graduate student Huifeng Du; Zhiguang Liu, Jiafang Li (project supervisor), and Ling Lu at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing; and Zhi-Yuan Li at the South China University of Technology. The work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the U.S Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

The researchers have also provided some GIFs,

And,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nano-kirigami with giant optical chirality by Zhiguang Liu, Huifeng Du, Jiafang Li, Ling Lu, Zhi-Yuan Li, and Nicholas X. Fang. Science Advances 06 Jul 2018: Vol. 4, no. 7, eaat4436 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat4436

This paper is open access.