Swiss and US scientists have developed a nanoporous crystal that could be used to clean up nuclear waste gases according to a June 13, 2016 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

An international team of scientists at EPFL [École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland] and the US have discovered a material that can clear out radioactive waste from nuclear plants more efficiently, cheaply, and safely than current methods.

Nuclear energy is one of the cheapest alternatives to carbon-based fossil fuels. But nuclear-fuel reprocessing plants generate waste gas that is currently too expensive and dangerous to deal with. Scanning hundreds of thousands of materials, scientists led by EPFL and their US colleagues have now discovered a material that can absorb nuclear waste gases much more efficiently, cheaply and safely. The work is published in Nature Communications (“Metal–organic framework with optimally selective xenon adsorption and separation”).

A June 14, 2016 EPFL press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explains further,

Nuclear-fuel reprocessing plants generate volatile radionuclides such as xenon and krypton, which escape in the so-called “off-gas” of these facilities – the gases emitted as byproducts of the chemical process. Current ways of capturing and clearing out these gases involve distillation at very low temperatures, which is expensive in both terms of energy and capital costs, and poses a risk of explosion.

Scientists led by Berend Smit’s lab at EPFL (Sion) and colleagues in the US, have now identified a material that can be used as an efficient, cheaper, and safer alternative to separate xenon and krypton – and at room temperature. The material, abbreviated as SBMOF-1, is a nanoporous crystal and belongs a class of materials that are currently used to clear out CO2 emissions and other dangerous pollutants. These materials are also very versatile, and scientists can tweak them to self-assemble into ordered, pre-determined crystal structures. In this way, they can synthesize millions of tailor-made materials that can be optimized for gas storage separation, catalysis, chemical sensing and optics.

The scientists carried out high-throughput screening of large material databases of over 125,000 candidates. To do this, they used molecular simulations to find structures that can separate xenon and krypton, and under conditions that match those involved in reprocessing nuclear waste.

Because xenon has a much shorter half-life than krypton – a month versus a decade – the scientists had to find a material that would be selective for both but would capture them separately. As xenon is used in commercial lighting, propulsion, imaging, anesthesia and insulation, it can also be sold back into the chemical market to offset costs.

The scientists identified and confirmed that SBMOF-1 shows remarkable xenon capturing capacity and xenon/krypton selectivity under nuclear-plant conditions and at room temperature.

The US partners have also made an announcement with this June 13, 2016 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) news release (also on EurekAlert), Note: It is a little repetitive but there’s good additional information,

Researchers are investigating a new material that might help in nuclear fuel recycling and waste reduction by capturing certain gases released during reprocessing. Conventional technologies to remove these radioactive gases operate at extremely low, energy-intensive temperatures. By working at ambient temperature, the new material has the potential to save energy, make reprocessing cleaner and less expensive. The reclaimed materials can also be reused commercially.

Appearing in Nature Communications, the work is a collaboration between experimentalists and computer modelers exploring the characteristics of materials known as metal-organic frameworks.

“This is a great example of computer-inspired material discovery,” said materials scientist Praveen Thallapally of the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “Usually the experimental results are more realistic than computational ones. This time, the computer modeling showed us something the experiments weren’t telling us.”

Waste avoidance

Recycling nuclear fuel can reuse uranium and plutonium — the majority of the used fuel — that would otherwise be destined for waste. Researchers are exploring technologies that enable safe, efficient, and reliable recycling of nuclear fuel for use in the future.

A multi-institutional, international collaboration is studying materials to replace costly, inefficient recycling steps. One important step is collecting radioactive gases xenon and krypton, which arise during reprocessing. To capture xenon and krypton, conventional technologies use cryogenic methods in which entire gas streams are brought to a temperature far below where water freezes — such methods are energy intensive and expensive.

Thallapally, working with Maciej Haranczyk and Berend Smit of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory [LBNL] and others, has been studying materials called metal-organic frameworks, also known as MOFs, that could potentially trap xenon and krypton without having to use cryogenics.

These materials have tiny pores inside, so small that often only a single molecule can fit inside each pore. When one gas species has a higher affinity for the pore walls than other gas species, metal-organic frameworks can be used to separate gaseous mixtures by selectively adsorbing.

To find the best MOF for xenon and krypton separation, computational chemists led by Haranczyk and Smit screened 125,000 possible MOFs for their ability to trap the gases. Although these gases can come in radioactive varieties, they are part of a group of chemically inert elements called “noble gases.” The team used computing resources at NERSC, the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility at LBNL.

“Identifying the optimal material for a given process, out of thousands of possible structures, is a challenge due to the sheer number of materials. Given that the characterization of each material can take up to a few hours of simulations, the entire screening process may fill a supercomputer for weeks,” said Haranczyk. “Instead, we developed an approach to assess the performance of materials based on their easily computable characteristics. In this case, seven different characteristics were necessary for predicting how the materials behaved, and our team’s grad student Cory Simon’s application of machine learning techniques greatly sped up the material discovery process by eliminating those that didn’t meet the criteria.”

The team’s models identified the MOF that trapped xenon most selectively and had a pore size close to the size of a xenon atom — SBMOF-1, which they then tested in the lab at PNNL.

After optimizing the preparation of SBMOF-1, Thallapally and his team at PNNL tested the material by running a mixture of gases through it — including a non-radioactive form of xenon and krypton — and measuring what came out the other end. Oxygen, helium, nitrogen, krypton, and carbon dioxide all beat xenon out. This indicated that xenon becomes trapped within SBMOF-1’s pores until the gas saturates the material.

Other tests also showed that in the absence of xenon, SBMOF-1 captures krypton. During actual separations, then, operators would pass the gas streams through SBMOF-1 twice to capture both gases.

The team also tested SBMOF-1’s ability to hang onto xenon in conditions of high humidity. Humidity interferes with cryogenics, and gases must be dehydrated before putting them through the ultra-cold method, another time-consuming expense. SBMOF-1, however, performed quite admirably, retaining more than 85 percent of the amount of xenon in high humidity as it did in dry conditions.

The final step in collecting xenon or krypton gas would be to put the MOF material under a vacuum, which sucks the gas out of the molecular cages for safe storage. A last laboratory test examined how stable the material was by repeatedly filling it up with xenon gas and then vacuuming out the xenon. After 10 cycles of this, SBMOF-1 collected just as much xenon as the first cycle, indicating a high degree of stability for long-term use.

Thallapally attributes this stability to the manner in which SBMOF-1 interacts with xenon. Rather than chemical reactions between the molecular cages and the gases, the relationship is purely physical. The material can last a lot longer without constantly going through chemical reactions, he said.

A model finding

Although the researchers showed that SBMOF-1 is a good candidate for nuclear fuel reprocessing, getting these results wasn’t smooth sailing. In the lab, the researchers had followed a previously worked out protocol from Stony Brook University to prepare SBMOF-1. Part of that protocol requires them to “activate” SBMOF-1 by heating it up to 300 degrees Celsius, three times the temperature of boiling water.

Activation cleans out material left in the pores from MOF synthesis. Laboratory tests of the activated SBMOF-1, however, showed the material didn’t behave as well as it should, based on the computer modeling results.

The researchers at PNNL repeated the lab experiments. This time, however, they activated SBMOF-1 at a lower temperature, 100 degrees Celsius, or the actual temperature of boiling water. Subjecting the material to the same lab tests, the researchers found SBMOF-1 behaving as expected, and better than at the higher activation temperature.

But why? To figure out where the discrepancy came from, the researchers modeled what happened to SBMOF-1 at 300 degrees Celsius. Unexpectedly, the pores squeezed in on themselves.

“When we heated the crystal that high, atoms within the pore tilted and partially blocked the pores,” said Thallapally. “The xenon doesn’t fit.”

Armed with these new computational and experimental insights, the researchers can explore SBMOF-1 and other MOFs further for nuclear fuel recycling. These MOFs might also be able to capture other noble gases such as radon, a gas known to pool in some basements.

Researchers hailed from several other institutions as well as those listed earlier, including University of California, Berkeley, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and IMDEA Materials Institute in Spain. This work was supported by the [US] Department of Energy Offices of Nuclear Energy and Science.

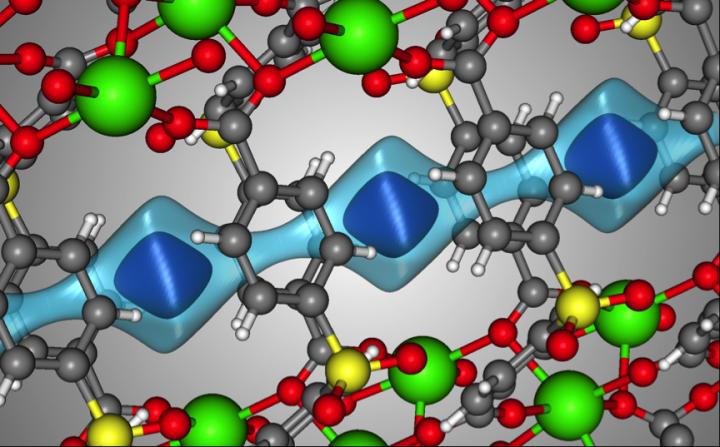

Here’s an image the researchers have provided to illustrate their work,

Caption: The crystal structure of SBMOF-1 (green = Ca, yellow = S, red = O, gray = C, white = H). The light blue surface is a visualization of the one-dimensional channel that SBMOF-1 creates for the gas molecules to move through. The darker blue surface illustrates where a Xe atom sits in the pores of SBMOF-1 when it adsorbs. Credit: Berend Smit/EPFL/University of California Berkley

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Metal–organic framework with optimally selective xenon adsorption and separation by Debasis Banerjee, Cory M. Simon, Anna M. Plonka, Radha K. Motkuri, Jian Liu, Xianyin Chen, Berend Smit, John B. Parise, Maciej Haranczyk, & Praveen K. Thallapally. Nature Communications 7, Article number: ncomms11831 doi:10.1038/ncomms11831 Published 13 June 2016

This paper is open access.

Final comment, this is the second time in the last month I’ve stumbled across more positive approaches to nuclear energy. The first time was a talk (Why Nuclear Power is Necessary) held in Vancouver, Canada in May 2016 (details here). I’m not trying to suggest anything unduly sinister but it is interesting since most of my adult life nuclear power has been viewed with fear and suspicion.