I have two items about thermochromic coatings. It’s a little confusing since the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), which publishes the journal featuring both papers has issued a news release that seemingly refers to both papers as a single piece of research.

Onto, the press/new releases from the research institutions to be followed by the AAAS news release.

Nanyang Technological University (NTU) does windows

A December 16, 2021 news item on Nanowerk announced work on energy-saving glass,

An international research team led by scientists from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has developed a material that, when coated on a glass window panel, can effectively self-adapt to heat or cool rooms across different climate zones in the world, helping to cut energy usage.

Developed by NTU researchers and reported in the journal Science (“Scalable thermochromic smart windows with passive radiative cooling regulation”), the first-of-its-kind glass automatically responds to changing temperatures by switching between heating and cooling.

The self-adaptive glass is developed using layers of vanadium dioxide nanoparticles composite, Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), and low-emissivity coating to form a unique structure which could modulate heating and cooling simultaneously.

…

A December 17, 2021 NTU press release (PDF), also on EurekAlert but published December 16, 2021, which originated the news item, delves further into the research (Note: A link has been removed),

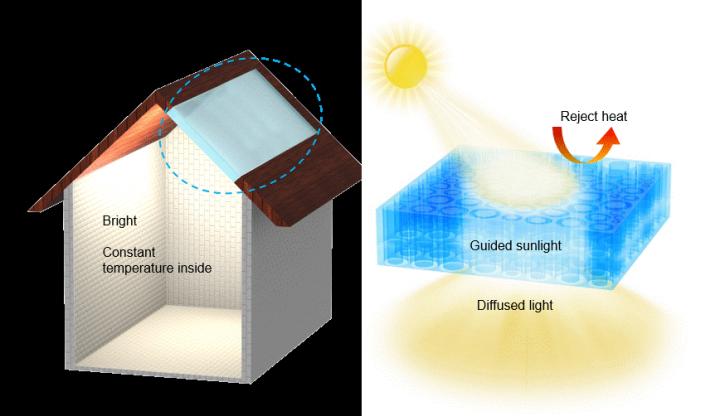

The newly developed glass, which has no electrical components, works by exploiting the spectrums of light responsible for heating and cooling.

During summer, the glass suppresses solar heating (near infrared light), while boosting radiative cooling (long-wave infrared) – a natural phenomenon where heat emits through surfaces towards the cold universe – to cool the room. In the winter, it does the opposite to warm up the room.

In lab tests using an infrared camera to visualise results, the glass allowed a controlled amount of heat to emit in various conditions (room temperature – above 70°C), proving its ability to react dynamically to changing weather conditions.

New glass regulates both heating and cooling

Windows are one of the key components in a building’s design, but they are also the least energy-efficient and most complicated part. In the United States alone, window-associated energy consumption (heating and cooling) in buildings accounts for approximately four per cent of their total primary energy usage each year according to an estimation based on data available from the Department of Energy in US.[1]

While scientists elsewhere have developed sustainable innovations to ease this energy demand – such as using low emissivity coatings to prevent heat transfer and electrochromic glass that regulate solar transmission from entering the room by becoming tinted – none of the solutions have been able to modulate both heating and cooling at the same time, until now.

The principal investigator of the study, Dr Long Yi of the NTU School of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) said, “Most energy-saving windows today tackle the part of solar heat gain caused by visible and near infrared sunlight. However, researchers often overlook the radiative cooling in the long wavelength infrared. While innovations focusing on radiative cooling have been used on walls and roofs, this function becomes undesirable during winter. Our team has demonstrated for the first time a glass that can respond favourably to both wavelengths, meaning that it can continuously self-tune to react to a changing temperature across all seasons.”

As a result of these features, the NTU research team believes their innovation offers a convenient way to conserve energy in buildings since it does not rely on any moving components, electrical mechanisms, or blocking views, to function.

To improve the performance of windows, the simultaneous modulation of both solar transmission and radiative cooling are crucial, said co-authors Professor Gang Tan from The University of Wyoming, USA, and Professor Ronggui Yang from the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, who led the building energy saving simulation.

“This innovation fills the missing gap between traditional smart windows and radiative cooling by paving a new research direction to minimise energy consumption,” said Prof Gang Tan.

The study is an example of groundbreaking research that supports the NTU 2025 strategic plan, which seeks to address humanity’s grand challenges on sustainability, and accelerate the translation of research discoveries into innovations that mitigate human impact on the environment.

Innovation useful for a wide range of climate types

As a proof of concept, the scientists tested the energy-saving performance of their invention using simulations of climate data covering all populated parts of the globe (seven climate zones).

The team found the glass they developed showed energy savings in both warm and cool seasons, with an overall energy saving performance of up to 9.5%, or ~330,000 kWh per year (estimated energy required to power 60 household in Singapore for a year) less than commercially available low emissivity glass in a simulated medium sized office building.

First author of the study Wang Shancheng, who is Research Fellow and former PhD student of Dr Long Yi, said, “The results prove the viability of applying our glass in all types of climates as it is able to help cut energy use regardless of hot and cold seasonal temperature fluctuations. This sets our invention apart from current energy-saving windows which tend to find limited use in regions with less seasonal variations.”

Moreover, the heating and cooling performance of their glass can be customised to suit the needs of the market and region for which it is intended.

“We can do so by simply adjusting the structure and composition of special nanocomposite coating layered onto the glass panel, allowing our innovation to be potentially used across a wide range of heat regulating applications, and not limited to windows,” Dr Long Yi said.

Providing an independent view, Professor Liangbing Hu, Herbert Rabin Distinguished Professor, Director of the Center for Materials Innovation at the University of Maryland, USA, said, “Long and co-workers made the original development of smart windows that can regulate the near-infrared sunlight and the long-wave infrared heat. The use of this smart window could be highly important for building energy-saving and decarbonization.”

A Singapore patent has been filed for the innovation. As the next steps, the research team is aiming to achieve even higher energy-saving performance by working on the design of their nanocomposite coating.

The international research team also includes scientists from Nanjing Tech University, China. The study is supported by the Singapore-HUJ Alliance for Research and Enterprise (SHARE), under the Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme, Minster of Education Research Fund Tier 1, and the Sino-Singapore International Joint Research Institute.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Scalable thermochromic smart windows with passive radiative cooling regulation by Shancheng Wang, Tengyao Jiang, Yun Meng, Ronggui Yang, Gang Tan, and Yi Long. Science • 16 Dec 2021 • Vol 374, Issue 6574 • pp. 1501-1504 • DOI: 10.1126/science.abg0291

This paper is behind a paywall.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab; LBNL) does roofs

A December 16, 2021 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert) announces an energy-saving coating for roofs (Note: Links have been removed),

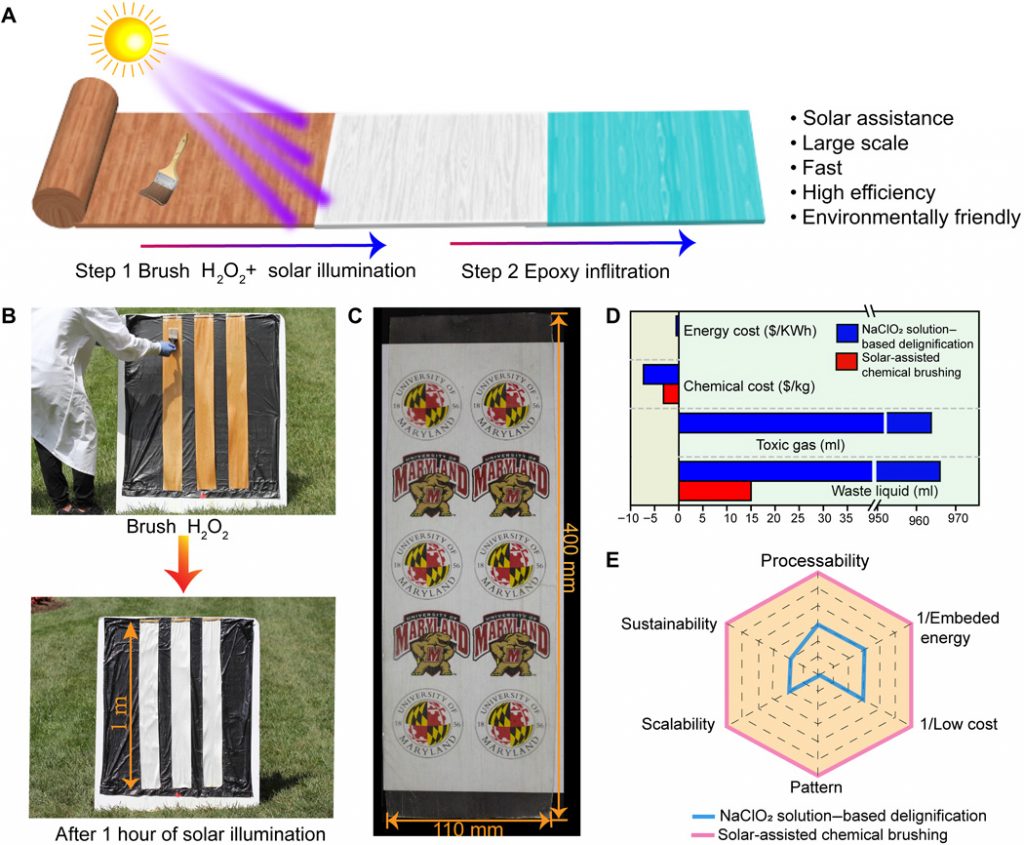

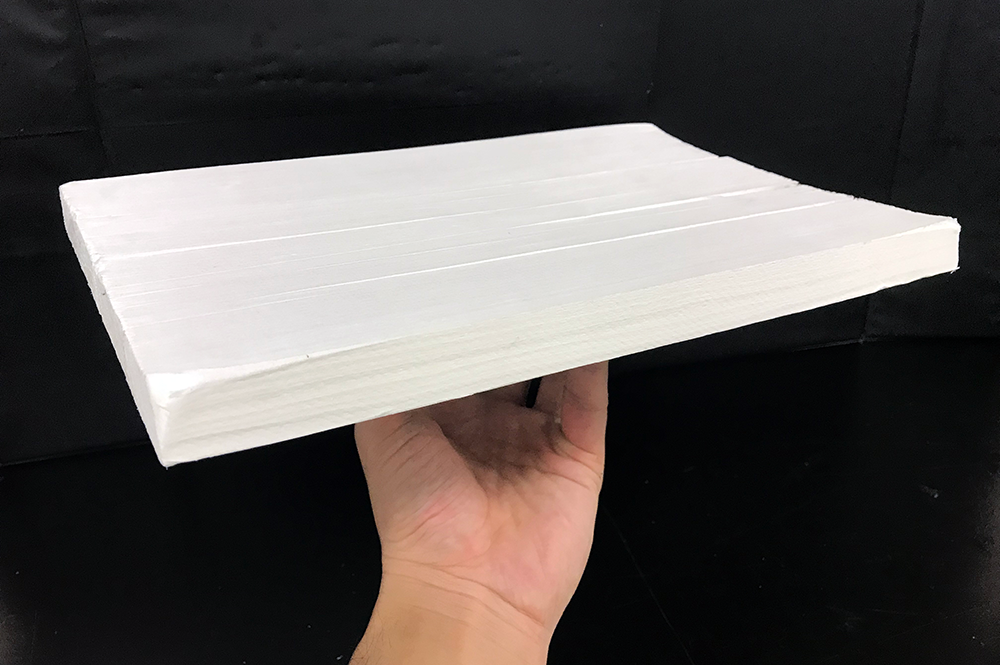

Scientists have developed an all-season smart-roof coating that keeps homes warm during the winter and cool during the summer without consuming natural gas or electricity. Research findings reported in the journal Science point to a groundbreaking technology that outperforms commercial cool-roof systems in energy savings.

“Our all-season roof coating automatically switches from keeping you cool to warm, depending on outdoor air temperature. This is energy-free, emission-free air conditioning and heating, all in one device,” said Junqiao Wu, a faculty scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a UC Berkeley professor of materials science and engineering who led the study.

Today’s cool roof systems, such as reflective coatings, membranes, shingles, or tiles, have light-colored or darker “cool-colored” surfaces that cool homes by reflecting sunlight. These systems also emit some of the absorbed solar heat as thermal-infrared radiation; in this natural process known as radiative cooling, thermal-infrared light is radiated away from the surface.

The problem with many cool-roof systems currently on the market is that they continue to radiate heat in the winter, which drives up heating costs, Wu explained.

“Our new material – called a temperature-adaptive radiative coating or TARC – can enable energy savings by automatically turning off the radiative cooling in the winter, overcoming the problem of overcooling,” he said.

A roof for all seasons

Metals are typically good conductors of electricity and heat. In 2017, Wu and his research team discovered that electrons in vanadium dioxide behave like a metal to electricity but an insulator to heat – in other words, they conduct electricity well without conducting much heat. “This behavior contrasts with most other metals where electrons conduct heat and electricity proportionally,” Wu explained.

Vanadium dioxide below about 67 degrees Celsius (153 degrees Fahrenheit) is also transparent to (and hence not absorptive of) thermal-infrared light. But once vanadium dioxide reaches 67 degrees Celsius, it switches to a metal state, becoming absorptive of thermal-infrared light. This ability to switch from one phase to another – in this case, from an insulator to a metal – is characteristic of what’s known as a phase-change material.

To see how vanadium dioxide would perform in a roof system, Wu and his team engineered a 2-centimeter-by-2-centimeter TARC thin-film device.

TARC “looks like Scotch tape, and can be affixed to a solid surface like a rooftop,” Wu said.

In a key experiment, co-lead author Kechao Tang set up a rooftop experiment at Wu’s East Bay home last summer to demonstrate the technology’s viability in a real-world environment.

A wireless measurement device set up on Wu’s balcony continuously recorded responses to changes in direct sunlight and outdoor temperature from a TARC sample, a commercial dark roof sample, and a commercial white roof sample over multiple days.

How TARC outperforms in energy savings

The researchers then used data from the experiment to simulate how TARC would perform year-round in cities representing 15 different climate zones across the continental U.S.

Wu enlisted Ronnen Levinson, a co-author on the study who is a staff scientist and leader of the Heat Island Group in Berkeley Lab’s Energy Technologies Area, to help them refine their model of roof surface temperature. Levinson developed a method to estimate TARC energy savings from a set of more than 100,000 building energy simulations that the Heat Island Group previously performed to evaluate the benefits of cool roofs and cool walls across the United States.

Finnegan Reichertz, a 12th grade student at the East Bay Innovation Academy in Oakland who worked remotely as a summer intern for Wu last year, helped to simulate how TARC and the other roof materials would perform at specific times and on specific days throughout the year for each of the 15 cities or climate zones the researchers studied for the paper.

The researchers found that TARC outperforms existing roof coatings for energy saving in 12 of the 15 climate zones, particularly in regions with wide temperature variations between day and night, such as the San Francisco Bay Area, or between winter and summer, such as New York City.

“With TARC installed, the average household in the U.S. could save up to 10% electricity,” said Tang, who was a postdoctoral researcher in the Wu lab at the time of the study. He is now an assistant professor at Peking University in Beijing, China.

Standard cool roofs have high solar reflectance and high thermal emittance (the ability to release heat by emitting thermal-infrared radiation) even in cool weather.

According to the researchers’ measurements, TARC reflects around 75% of sunlight year-round, but its thermal emittance is high (about 90%) when the ambient temperature is warm (above 25 degrees Celsius or 77 degrees Fahrenheit), promoting heat loss to the sky. In cooler weather, TARC’s thermal emittance automatically switches to low, helping to retain heat from solar absorption and indoor heating, Levinson said.

Findings from infrared spectroscopy experiments using advanced tools at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry validated the simulations.

“Simple physics predicted TARC would work, but we were surprised it would work so well,” said Wu. “We originally thought the switch from warming to cooling wouldn’t be so dramatic. Our simulations, outdoor experiments, and lab experiments proved otherwise – it’s really exciting.”

The researchers plan to develop TARC prototypes on a larger scale to further test its performance as a practical roof coating. Wu said that TARC may also have potential as a thermally protective coating to prolong battery life in smartphones and laptops, and shield satellites and cars from extremely high or low temperatures. It could also be used to make temperature-regulating fabric for tents, greenhouse coverings, and even hats and jackets.

Co-lead authors on the study were Kaichen Dong and Jiachen Li.

The Molecular Foundry is a nanoscience user facility at Berkeley Lab.

This work was primarily supported by the DOE Office of Science and a Bakar Fellowship.

The technology is available for licensing and collaboration. If interested, please contact Berkeley Lab’s Intellectual Property Office, ipo@lbl.gov.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Temperature-adaptive radiative coating for all-season household thermal regulation by Kechao Tang, Kaichen Dong, Jiachen Li, Madeleine P. Gordon, Finnegan G. Reichertz, Hyungjin Kim, Yoonsoo Rho, Qingjun Wang, Chang-Yu Lin, Costas P. Grigoropoulos, Ali Javey, Jeffrey J. Urban, Jie Yao, Ronnen Levinson, Junqiao Wu. Science • 16 Dec 2021 • Vol 374, Issue 6574 • pp. 1504-1509 • DOI: 10.1126/science.abf7136

This paper is behind a paywall.

An interesting news release from the AAAS

While it’s a little confusing as it cites only the ‘window’ research from NTU, the body of this news release offers some additional information about the usefulness of thermochromic materials and seemingly refers to both papers, from a December 16, 2021 AAAS news release,

Temperature-adaptive passive radiative cooling for roofs and windows

…

When it’s cold out, window glass and roof coatings that use passive radiative cooling to keep buildings cool can be designed to passively turn off radiative cooling to avoid heat loss, two new studies show. Their proof-of-concept analyses demonstrate that passive radiative cooling can be expanded to warm and cold climate applications and regions, potentially providing all-season energy savings worldwide. Buildings consume roughly 40% of global energy, a large proportion of which is used to keep them cool in warmer climates. However, most temperature regulation systems commonly employed are not very energy efficient and require external power or resources. In contrast, passive radiative cooling technologies, which use outer space as a near-limitless natural heat sink, have been extensively examined as a means of energy-efficient cooling for buildings. This technology uses materials designed to selectively emit narrow-band radiation through the infrared atmospheric window to disperse heat energy into the coldness of space. However, while this approach has proven effective in cooling buildings to below ambient temperatures, it is only helpful during the warmer months or in regions that are perpetually hot. Furthermore, the inability to “turn off” passive cooling in cooler climes or in regions with large seasonal temperature variations means that continuous cooling during colder periods would exacerbate the energy costs of heating. In two different studies, by Shancheng Wang and colleagues and Kechao Tang and colleagues, researchers approach passive radiative cooling from an all-season perspective and present a new, scalable temperature-adaptive radiative technology that passively turns off radiative cooling at lower temperatures. Wang et al. and Tang et al. achieve this using a tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide and show how it can be applied to create both window glass and a flexible roof coating, respectively. Model simulations of the self-adapting materials suggest they could provide year-round energy savings across most climate zones, especially those with substantial seasonal temperature variations.

…

I wish them all good luck with getting these materials to market.