Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) are calling it a new ‘living material’ according to a Feb. 16, 2017 news item on Nanowerk,

Engineers and biologists at MIT have teamed up to design a new “living material” — a tough, stretchy, biocompatible sheet of hydrogel injected with live cells that are genetically programmed to light up in the presence of certain chemicals.

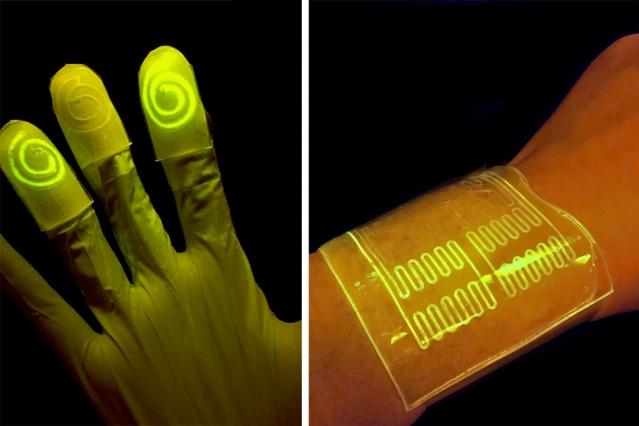

Researchers have found that the hydrogel’s mostly watery environment helps keep nutrients and programmed bacteria alive and active. When the bacteria reacts to a certain chemical, the bacteria are programmed to light up, as seen on the left. Courtesy of the researchers

A Feb. 15, 2017 MIT news release, which originated the news item, provides more information about this work,

In a paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers demonstrate the new material’s potential for sensing chemicals, both in the environment and in the human body.

The team fabricated various wearable sensors from the cell-infused hydrogel, including a rubber glove with fingertips that glow after touching a chemically contaminated surface, and bandages that light up when pressed against chemicals on a person’s skin.

Xuanhe Zhao, the Robert N. Noyce Career Development associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, says the group’s living material design may be adapted to sense other chemicals and contaminants, for uses ranging from crime scene investigation and forensic science, to pollution monitoring and medical diagnostics.

“With this design, people can put different types of bacteria in these devices to indicate toxins in the environment, or disease on the skin,” says Timothy Lu, associate professor of biological engineering and of electrical engineering and computer science. “We’re demonstrating the potential for living materials and devices.”

The paper’s co-authors are graduate students Xinyue Liu, Tzu-Chieh Tang, Eleonore Tham, Hyunwoo Yuk, and Shaoting Lin.

Infusing life in materials

Lu and his colleagues in MIT’s Synthetic Biology Group specialize in creating biological circuits, genetically reprogramming the biological parts in living cells such as E. coli to work together in sequence, much like logic steps in an electrical circuit. In this way, scientists can reengineer living cells to carry out specific functions, including the ability to sense and signal the presence of viruses and toxins.

However, many of these newly programmed cells have only been demonstrated in situ, within Petri dishes, where scientists can carefully control the nutrient levels necessary to keep the cells alive and active — an environment that has proven extremely difficult to replicate in synthetic materials.

“The challenge to making living materials is how to maintain those living cells, to make them viable and functional in the device,” Lu says. “They require humidity, nutrients, and some require oxygen. The second challenge is how to prevent them from escaping from the material.”

To get around these roadblocks, others have used freeze-dried chemical extracts from genetically engineered cells, incorporating them into paper to create low-cost, virus-detecting diagnostic strips. But extracts, Lu says, are not the same as living cells, which can maintain their functionality over a longer period of time and may have higher sensitivity for detecting pathogens.

Other groups have seeded heart muscle cells onto thin rubber films to make soft, “living” actuators, or robots. When bent repeatedly, however, these films can crack, allowing the live cells to leak out.

A lively host

Zhao’s group in MIT’s Soft Active Materials Laboratory has developed a material that may be ideal for hosting living cells. For the past few years, his team has come up with various formulations of hydrogel — a tough, highly stretchable, biocompatible material made from a mix of polymer and water. Their latest designs have contained up to 95 percent water, providing an environment which Zhao and Lu recognized might be suitable for sustaining living cells. The material also resists cracking even when repeatedly stretched and pulled — a property that could help contain cells within the material.

The two groups teamed up to integrate Lu’s genetically programmed bacterial cells into Zhao’s sheets of hydrogel material. They first fabricated layers of hydrogel and patterned narrow channels within the layers using 3-D printing and micromolding techniques. They fused the hydrogel to a layer of elastomer, or rubber, that is porous enough to let in oxygen. They then injected E. coli cells into the hydrogel’s channels. The cells were programmed to fluoresce, or light up, when in contact with certain chemicals that pass through the hydrogel, in this case a natural compound known as DAPG (2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol).

The researchers then soaked the hydrogel/elastomer material in a bath of nutrients which infused throughout the hydrogel and helped to keep the bacterial cells alive and active for several days.

To demonstrate the material’s potential uses, the researchers first fabricated a sheet of the material with four separate, narrow channels, each containing a type of bacteria engineered to glow green in response to a different chemical compound. They found each channel reliably lit up when exposed to its respective chemical.

Next, the team fashioned the material into a bandage, or “living patch,” patterned with channels containing bacteria sensitive to rhamnose, a naturally occurring sugar. The researchers swabbed a volunteer’s wrist with a cotton ball soaked in rhamnose, then applied the hydrogel patch, which instantly lit up in response to the chemical.

Finally, the researchers fabricated a hydrogel/elastomer glove whose fingertips contained swirl-like channels, each of which they filled with different chemical-sensing bacterial cells. Each fingertip glowed in response to picking up a cotton ball soaked with a respective compound.

The group has also developed a theoretical model to help guide others in designing similar living materials and devices.

“The model helps us to design living devices more efficiently,” Zhao says. “It tells you things like the thickness of the hydrogel layer you should use, the distance between channels, how to pattern the channels, and how much bacteria to use.”

Ultimately, Zhao envisions products made from living materials, such as gloves and rubber soles lined with chemical-sensing hydrogel, or bandages, patches, and even clothing that may detect signs of infection or disease.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Stretchable living materials and devices with hydrogel–elastomer hybrids hosting programmed cells by Xinyue Liu, Tzu-Chieh Tang, Eléonore Tham, Hyunwoo Yuk, Shaoting Lin, Timothy K. Lu, and Xuanhe Zhao. PNAS February 15, 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618307114 Published online before print February 15, 2017

This paper appears to be open access.