What impact does a droplet make on a solid surface? It’s not the first question that comes to my mind but scientists have been studying it for over a century. From an Aug. 5, 2015 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

Studies of the impact a droplet makes on solid surfaces hark back more than a century. And until now, it was generally believed that a droplet’s impact on a solid surface could always be separated into two phases: spreading and retracting. But it’s much more complex than that, as a team of researchers from City University of Hong Kong, Ariel University in Israel, and Dalian University of Technology in China report in the journal Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing (“Controlling drop bouncing using surfaces with gradient features”).

An Aug. 4, 2015 American Institute of Physics news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the impact in detail,

“During the spreading phase, the droplet undergoes an inertia-dominant acceleration and spreads into a ‘pancake’ shape,” explained Zuankai Wang, an associate professor within the Department of Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering at the City University of Hong Kong. “And during the retraction phase, the drop minimizes its surface energy and pulls back inward.”

Remarkably, on gold standard superhydrophobic–a.k.a. repellant–surfaces such as lotus leaves, droplets jump off at the end of the retraction stage due to the minimal energy dissipation during the impact process. This is attributed to the presence of an air cushion within the rough surface.

There exists, however, a classical limit in terms of the contact time between droplets and the gold standard superhydrophobic materials inspired by lotus leaves.

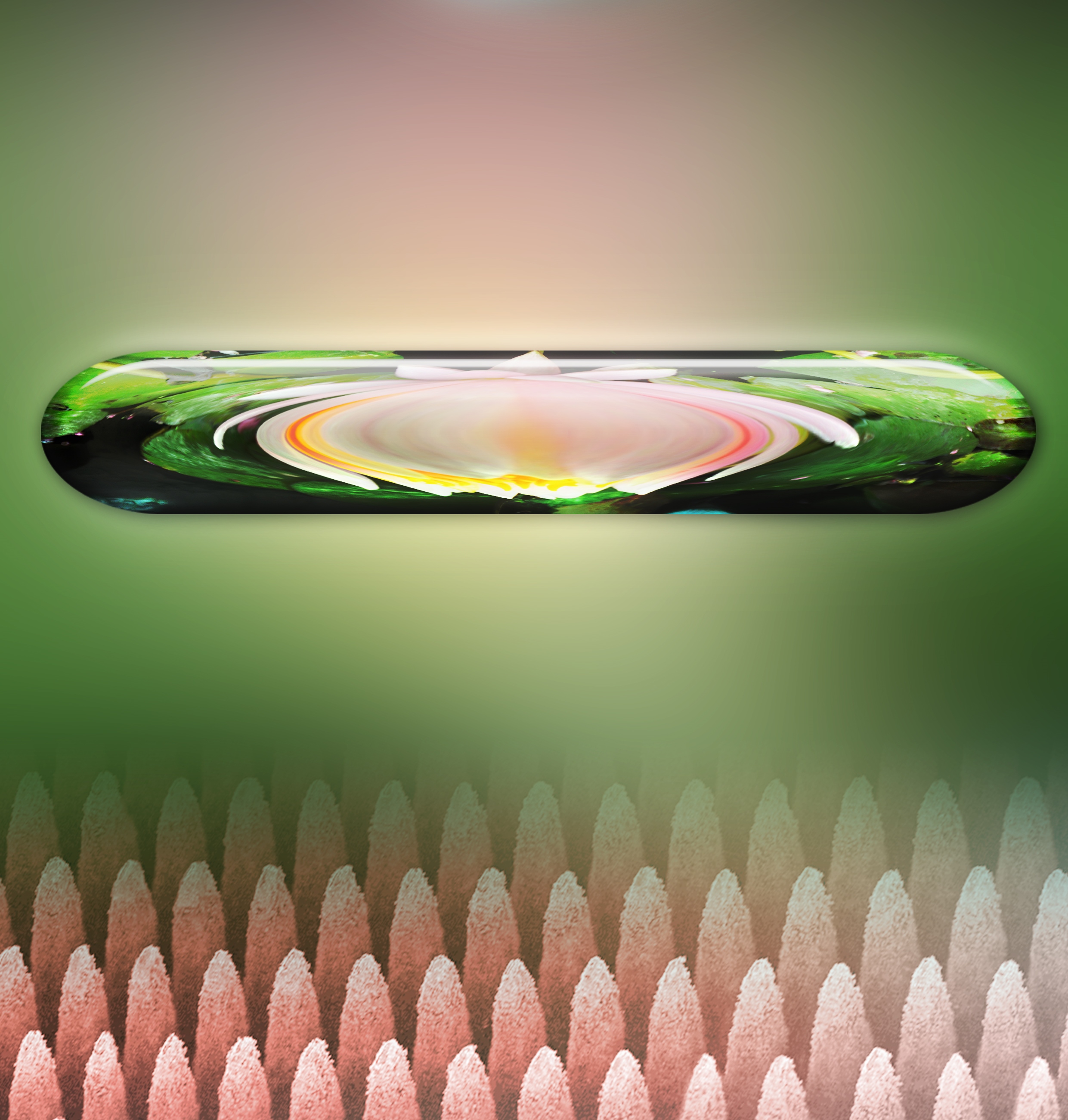

As the team previously reported in the journal Nature Physics, it’s possible to shape the droplet to bounce from the surface in a pancake shape directly at the end of the spreading stage without going through the receding process. As a result, the droplet can be shed away much faster.

“Interestingly, the contact time is constant under a wide range of impact velocities,” said Wang. “In other words: the contact time reduction is very efficient and robust, so the novel surface behaves like an elastic spring. But the real magic lies within the surface texture itself.”

To prevent the air cushion from collapsing or water from penetrating into the surface, conventional wisdom suggests the use of nanoscale posts with small inter-post spacings. “The smaller the inter-post spacings, the greater the impact velocity the small inter-post can withstand,” he elaborated. “By contrast, designing a surface with macrostructures–tapered sub-millimeter post arrays with a wide spacing–means that a droplet will shed from it much faster than any previously engineered materials.”

What the New Results Show

Despite exciting progress, rationally controlling the contact time and quantitatively predicting the critical Weber number–a number used in fluid mechanics to describe the ratio between deforming inertial forces and stabilizing cohesive forces for liquids flowing through a fluid medium–for the occurrence of pancake bouncing remained elusive.

So the team experimentally demonstrated that the drop bouncing is intricately influenced by the surface morphology. “Under the same center-to-center post spacing, surfaces with a larger apex angle can give rise to more pancake bouncing, which is characterized by a significant contact time reduction, smaller critical Weber number, and a wider Weber number range,” according to co-authors Gene Whyman and Edward Bormashenko, both professors at Ariel University.

Wang and colleagues went on to develop simple harmonic spring models to theoretically reveal the dependence of timescales associated with the impinging drop and the critical Weber number for pancake bouncing on the surface morphology. “The insights gained from this work will allow us to rationally design various surfaces for many practical applications,” he added.

The team’s novel surfaces feature a shortened contact time that prevents or slows ice formation. “Ice formation and its subsequent buildup hinder the operation of modern infrastructures–including aircraft, offshore oil platforms, air conditioning systems, wind turbines, power lines, and telecommunications equipment,” Wang said.

At supercooled temperatures, which involves lowering the temperature of a liquid or gas below its freezing point without it solidifying, the longer a droplet remains in contact with a surface before bouncing off the greater the chances are of it freezing in place. “Our new surface structure can be used to help prevent aircraft wings and engines from icing,” he said.

This is highly desirable, because a very light coating of snow or ice–light enough to be barely visible–is known to reduce the performance of airplanes and even cause crashes. One such disaster occurred in 2009, and called attention to the dangers of in-flight icing after it caused Air France Flight 447 flying from Rio de Janeiro to Paris to crash into the Atlantic Ocean.

Beyond anti-icing for aircraft, “turbine blades in power stations and wind farms can also benefit from an anti-icing surface by gaining a boost in efficiency,” he added.

As you can imagine, this type of nature-inspired surface shows potential for a tremendous range of other applications as well–everything from water and oil separation to disease transmission prevention.

The next step for the team? To “develop bioinspired ‘active’ materials that are adaptive to their environments and capable of self-healing,” said Wang.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Controlling drop bouncing using surfaces with gradient features by Yahua Liu, Gene Whyman, Edward Bormashenko, Chonglei Hao, and Zuankai Wang. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 051604 (2015); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4927055

This paper appears to be open access.

Finally, here’s an illustration of the pancake bounce,

Droplet hitting tapered posts shows “pancake” bouncing characterized by lifting off the surface of the end of spreading without retraction. Credit- Z.Wang/HKU

There is also a pancake bounce video which you can view here on EurekAlert.