I have two ‘mosquito and disease’ stories, the first concerning dengue fever and the second, malaria.

Dengue fever in Taiwan

A June 8, 2023 news item on phys.org features robotic vehicles, dengue fever, and mosquitoes,

Unmanned ground vehicles can be used to identify and eliminate the breeding sources of mosquitos that carry dengue fever in urban areas, according to a new study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases by Wei-Liang Liu of the Taiwan National Mosquito-Borne Diseases Control Research Center, and colleagues.

It turns out sewers are a problem according to this June 8, 2023 PLOS (Public Library of Science) news release on EurekAlert, provides more context and detail,

Dengue fever is an infectious disease caused by the dengue virus and spread by several mosquito species in the genus Aedes, which also spread chikungunya, yellow fever and zika. Through the process of urbanization, sewers have become easy breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitos and most current mosquito monitoring programs struggle to monitor and analyze the density of mosquitos in these hidden areas.

In the new control effort, researchers combined a crawling robot, wire-controlled cable car and real-time monitoring system into an unmanned ground vehicle system (UGV) that can take high-resolution, real-time images of areas within sewers. From May to August 2018, the system was deployed in five administrative districts in Kaohsiung city, Taiwan, with covered roadside sewer ditches suspected to be hotspots for mosquitos. Mosquito gravitraps were places above the sewers to monitor effects of the UGV intervention on adult mosquitos in the area.

In 20.7% of inspected sewers, the system found traces of Aedes mosquitos in stages from larvae to adult. In positive sewers, additional prevention control measures were carried out, using either insecticides or high-temperature water jets. Immediately after these interventions, the gravitrap index (GI)— a measure of the adult mosquito density nearby— dropped significantly from 0.62 to 0.19.

“The widespread use of UGVs can potentially eliminate some of the breeding sources of vector mosquitoes, thereby reducing the annual prevalence of dengue fever in Kaohsiung city,” the authors say.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Use of unmanned ground vehicle systems in urbanized zones: A study of vector Mosquito surveillance in Kaohsiung by Yu-Xuan Chen, Chao-Ying Pan, Bo-Yu Chen, Shu-Wen Jeng, Chun-Hong Chen, Joh-Jong Huang, Chaur-Dong Chen, Wei-Liang Liu. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011346 Published: June 8, 2023

This paper is open access.

Dengue on the rise

Like many diseases, dengue is one where you may not have symptoms (asymptomatic), or they’re relatively mild and can be handled at home, or you may need care in a hospital and, in some cases, it can be fatal.

The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that dengue fever cases have increased exponentially since 2000 (from the March 17, 2023 version of the WHO’s “Dengue and severe dengue” fact sheet),

Global burden

The incidence of dengue has grown dramatically around the world in recent decades, with cases reported to WHO increased from 505 430 cases in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019. A vast majority of cases are asymptomatic or mild and self-managed, and hence the actual numbers of dengue cases are under-reported. Many cases are also misdiagnosed as other febrile illnesses (1).

One modelling estimate indicates 390 million dengue virus infections per year of which 96 million manifest clinically (2). Another study on the prevalence of dengue estimates that 3.9 billion people are at risk of infection with dengue viruses.

The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries in the WHO Regions of Africa, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. The Americas, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions are the most seriously affected, with Asia representing around 70% of the global disease burden.

Dengue is spreading to new areas including Europe, [emphasis mine] and explosive outbreaks are occurring. Local transmission was reported for the first time in France and Croatia in 2010 [emphasis mine] and imported cases were detected in 3 other European countries.

The largest number of dengue cases ever reported globally was in 2019. All regions were affected, and dengue transmission was recorded in Afghanistan for the first time. The American Region reported 3.1 million cases, with more than 25 000 classified as severe. A high number of cases were reported in Bangladesh (101 000), Malaysia (131 000) Philippines (420 000), Vietnam (320 000) in Asia.

Dengue continues to affect Brazil, Colombia, the Cook Islands, Fiji, India, Kenya, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, the Reunion Islands and Vietnam as of 2021.

There’s information from an earlier version of the fact sheet, in my July 2, 2013 posting, highlighting different aspects of the disease, e.g., “About 2.5% of those affected die.”

A July 21, 2023 United Nations press release warns that the danger from mosquitoes spreading dengue fever could increase along with the temperature,

Global warming marked by higher average temperatures, precipitation and longer periods of drought, could prompt a record number of dengue infections worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned on Friday [July 21, 2023].

Despite the absence of mosquitoes infected with the dengue virus in Canada, the government has a Dengue fever information page. At this point, the concern is likely focused on travelers who’ve contracted the disease from elsewhere. However, I am guessing that researchers are keeping a close eye on Canadian mosquitoes as these situations can change.

Malaria in Florida (US)

The researchers from the University of Central Florida (UCF) couldn’t have known when they began their project to study mosquito bites and disease that Florida would register its first malaria cases in 20 years this summer, from a July 26, 2023 article by Stephanie Colombini for NPR ([US] National Public Radio), Note: Links have been removed,

…

First local transmission in U.S. in 20 years

Heath [Hannah Heath] is one of eight known people in recent months who have contracted malaria in the U.S., after being bitten by a local mosquito, rather than while traveling abroad. The cases comprise the nation’s first locally transmitted outbreak in 20 years. The last time this occurred was in 2003, when eight people tested positive for malaria in Palm Beach, Fla.

One of the eight cases is in Texas; the rest occurred in the northern part of Sarasota County.

The Florida Department of Health recorded the most recent case in its weekly arbovirus report for July 9-15 [2023].

For the past month, health officials have issued a mosquito-borne illness alert for residents in Sarasota and neighboring Manatee County. Mosquito management teams are working to suppress the population of the type of mosquito that carries malaria, Anopheles.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital has treated five of the county’s seven malaria patients, according to Dr. Manuel Gordillo, director of infection control.

“The cases that are coming in are classic malaria, you know they come in with fever, body aches, headaches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,” Gordillo said, explaining that his hospital usually treats just one or two patients a year who acquire malaria while traveling abroad in Central or South America, or Africa.

…

All the locally acquired cases were of Plasmodium vivax malaria, a strain that typically produces milder symptoms or can even be asymptomatic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the strain can still cause death, and pregnant people and children are particularly vulnerable.

…

Malaria does not spread from human-to-human contact; a mosquito carrying the disease has to bite someone to transmit the parasites.

Workers with Sarasota County Mosquito Management Services have been especially busy since May 26 [2023], when the first local case was confirmed.

Like similar departments across Florida, the team is experienced in responding to small outbreaks of mosquito-borne illnesses such as West Nile virus or dengue. They have protocols for addressing travel-related cases of malaria as well, but have ramped up their efforts now that they have confirmation that transmission is occurring locally between mosquitoes and humans.

…

While organizations like the World Health Organization have cautioned climate change could lead to more global cases and deaths from malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases, experts say it’s too soon to tell if the local transmission seen these past two months has any connection to extreme heat or flooding.

“We don’t have any reason to think that climate change has contributed to these particular cases,” said Ben Beard, deputy director of the CDC’s US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] division of vector-borne diseases and deputy incident manager for this year’s local malaria response.

“In a more general sense though, milder winters, earlier springs, warmer, longer summers – all of those things sort of translate into mosquitoes coming out earlier, getting their replication cycles sooner, going through those cycles faster and being out longer,” he said. And so we are concerned about the impact of climate change and environmental change in general on what we call vector-borne diseases.”.

Beard co-authored a 2019 report that highlights a significant increase in diseases spread by ticks and mosquitoes in recent decades. Lyme disease and West Nile virus were among the top five most prevalent.

“In the big picture it’s a very significant concern that we have,” he said.

…

Engineered tissue and bloodthirsty mosquitoes

A June 8, 2023 University of Central Florida (UCF) news release (also on EurekAlert) by Eric Eraso describes the research into engineered human tissue and features a ‘bloodthirsty’ video. First, the video,

Note: A link has been removed,

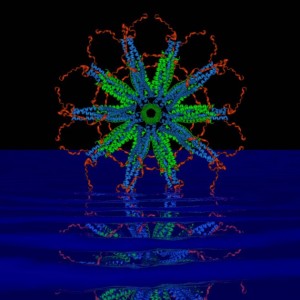

A UCF research team has engineered tissue with human cells that mosquitoes love to bite and feed upon — with the goal of helping fight deadly diseases transmitted by the biting insects.

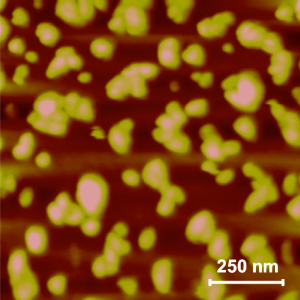

A multidisciplinary team led by College of Medicine biomedical researcher Bradley Jay Willenberg with Mollie Jewett (UCF Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences) and Andrew Dickerson (University of Tennessee) lined 3D capillary gel biomaterials with human cells to create engineered tissue and then infused it with blood. Testing showed mosquitoes readily bite and blood feed on the constructs. Scientists hope to use this new platform to study how pathogens that mosquitoes carry impact and infect human cells and tissues. Presently, researchers rely largely upon animal models and cells cultured on flat dishes for such investigations.

Further, the new system holds great promise for blood feeding mosquito species that have proven difficult to rear and maintain as colonies in the laboratory, an important practical application. The Willenberg team’s work was published Friday in the journal Insects.

Mosquitos have often been called the world’s deadliest animal, as vector-borne illnesses, including those from mosquitos cause more than 700,000 deaths worldwide each year. Malaria, dengue, Zika virus and West Nile virus are all transmitted by mosquitos. Even for those who survive these illnesses, many are left suffering from organ failure, seizures and serious neurological impacts.

“Many people get sick with mosquito-borne illnesses every year, including in the United States. The toll of such diseases can be especially devastating for many countries around the world,” Willenberg says.

This worldwide impact of mosquito-borne disease is what drives Willenberg, whose lab employs a unique blend of biomedical engineering, biomaterials, tissue engineering, nanotechnology and vector biology to develop innovative mosquito surveillance, control and research tools. He said he hopes to adapt his new platform for application to other vectors such as ticks, which spread Lyme disease.

“We have demonstrated the initial proof-of-concept with this prototype” he says. “I think there are many potential ways to use this technology.”

Captured on video, Willenberg observed mosquitoes enthusiastically blood feeding from the engineered tissue, much as they would from a human host. This demonstration represents the achievement of a critical milestone for the technology: ensuring the tissue constructs were appetizing to the mosquitoes.

“As one of my mentors shared with me long ago, the goal of physicians and biomedical researchers is to help reduce human suffering,” he says. “So, if we can provide something that helps us learn about mosquitoes, intervene with diseases and, in some way, keep mosquitoes away from people, I think that is a positive.”

Willenberg came up with the engineered tissue idea when he learned the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was looking for new in vitro 3D models that could help study pathogens that mosquitoes and other biting arthropods carry.

“When I read about the NIH seeking these models, it got me thinking that maybe there is a way to get the mosquitoes to bite and blood feed [on the 3D models] directly,” he says. “Then I can bring in the mosquito to do the natural delivery and create a complete vector-host-pathogen interface model to study it all together.”

As this platform is still in its early stages, Willenberg wants to incorporate addition types of cells to move the system closer to human skin. He is also developing collaborations with experts that study pathogens and work with infected vectors, and is working with mosquito control organizations to see how they can use the technology.

“I have a particular vision for this platform, and am going after it. My experience too is that other good ideas and research directions will flourish when it gets into the hands of others,” he says. “At the end of the day, the collective ideas and efforts of the various research communities propel a system like ours to its full potential. So, if we can provide them tools to enable their work, while also moving ours forward at the same time, that is really exciting.”

Willenberg received his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering from the University of Florida and continued there for his postdoctoral training and then in scientist, adjunct scientist and lecturer positions. He joined the UCF College of Medicine in 2014, where he is currently an assistant professor of medicine.

Willenberg is also a co-founder, co-owner and manager of Saisijin Biotech, LLC and has a minor ownership stake in Sustained Release Technologies, Inc. Neither entity was involved in any way with the work presented in this story. Team members may also be listed as inventors on patent/patent applications that could result in royalty payments. This technology is available for licensing. To learn more, please visit ucf.flintbox.com/technologies/44c06966-2748-4c14-87d7-fc40cbb4f2c6.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Engineered Human Tissue as A New Platform for Mosquito Bite-Site Biology Investigations by Corey E. Seavey, Mona Doshi, Andrew P. Panarello, Michael A. Felice, Andrew K. Dickerson, Mollie W. Jewett and Bradley J. Willenberg. Insects 2023, 14(6), 514; https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060514 Published: 2 June 2023

This paper is open access.

That final paragraph in the news release is new to me. I’ve seen them list companies where the researchers have financial interests but this is the first time I’ve seen a news release that offers a statement attempting to cover all the bases including some future possibilities such as: “Team members may also be listed as inventors on patent/patent applications that could result in royalty payments.“

It seems pretty clear that there’s increasing concern about mosquito-borne diseases no matter where you live.