Who is an artist? What is an artist? Can everyone be an artist? These are the kinds of questions you can expect with the rise of artificially intelligent artists/collaborators. Of course, these same questions have been asked many times before the rise of AI (artificial intelligence) agents/programs in the field of visual art. Each time the questions are raised is an opportunity to examine our beliefs from a different perspective. And, not to be forgotten, there are questions about money.

The shock

First, the ‘art’,

Shanti Escalante-De Mattei’s September 1, 2022 article for ArtNews.com provides an overview of the latest AI art controversy (Note: A link has been removed),

The debate around AI art went viral once again when a man won first place at the Colorado State Fair’s art competition in the digital category with a work he made using text-to-image AI generator Midjourney.

Twitter user and digital artist Genel Jumalon tweeted out a screenshot from a Discord channel in which user Sincarnate, aka game designer Jason Allen, celebrated his win at the fair. Jumalon wrote, “Someone entered an art competition with an AI-generated piece and won the first prize. Yeah that’s pretty fucking shitty.”

The comments on the post range from despair and anger as artists, both digital and traditional, worry that their livelihoods might be at stake after years of believing that creative work would be safe from AI-driven automation. [emphasis mine]

…

Rachel Metz’s September 3, 2022 article for CNN provides more details about how the work was generated (Note: Links have been removed),

Jason M. Allen was almost too nervous to enter his first art competition. Now, his award-winning image is sparking controversy about whether art can be generated by a computer, and what, exactly, it means to be an artist.

In August [2022], Allen, a game designer who lives in Pueblo West, Colorado, won first place in the emerging artist division’s “digital arts/digitally-manipulated photography” category at the Colorado State Fair Fine Arts Competition. His winning image, titled “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” (French for “Space Opera Theater”), was made with Midjourney — an artificial intelligence system that can produce detailed images when fed written prompts. A $300 prize accompanied his win.

…

Allen’s winning image looks like a bright, surreal cross between a Renaissance and steampunk painting. It’s one of three such images he entered in the competition. In total, 11 people entered 18 pieces of art in the same category in the emerging artist division.

The definition for the category in which Allen competed states that digital art refers to works that use “digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process.” Allen stated that Midjourney was used to create his image when he entered the contest, he said.

…

The newness of these tools, how they’re used to produce images, and, in some cases, the gatekeeping for access to some of the most powerful ones has led to debates about whether they can truly make art or assist humans in making art.

This came into sharp focus for Allen not long after his win. Allen had posted excitedly about his win on Midjourney’s Discord server on August 25 [2022], along with pictures of his three entries; it went viral on Twitter days later, with many artists angered by Allen’s win because of his use of AI to create the image, as a story by Vice’s Motherboard reported earlier this week.

“This sucks for the exact same reason we don’t let robots participate in the Olympics,” one Twitter user wrote.

“This is the literal definition of ‘pressed a few buttons to make a digital art piece’,” another Tweeted. “AI artwork is the ‘banana taped to the wall’ of the digital world now.”

…

Yet while Allen didn’t use a paintbrush to create his winning piece, there was plenty of work involved, he said.

“It’s not like you’re just smashing words together and winning competitions,” he said.

You can feed a phrase like “an oil painting of an angry strawberry” to Midjourney and receive several images from the AI system within seconds, but Allen’s process wasn’t that simple. To get the final three images he entered in the competition, he said, took more than 80 hours.

First, he said, he played around with phrasing that led Midjourney to generate images of women in frilly dresses and space helmets — he was trying to mash up Victorian-style costuming with space themes, he said. Over time, with many slight tweaks to his written prompt (such as to adjust lighting and color harmony), he created 900 iterations of what led to his final three images. He cleaned up those three images in Photoshop, such as by giving one of the female figures in his winning image a head with wavy, dark hair after Midjourney had rendered her headless. Then he ran the images through another software program called Gigapixel AI that can improve resolution and had the images printed on canvas at a local print shop.

…

Ars Technica has run a number of articles on the subject of Art and AI, Benj Edwards in an August 31, 2022 article seems to have been one of the first to comment on Jason Allen’s win (Note 1: Links have been removed; Note 2: Look at how Edwards identifies Jason Allen as an artist),

A synthetic media artist named Jason Allen entered AI-generated artwork into the Colorado State Fair fine arts competition and announced last week that he won first place in the Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography category, Vice reported Wednesday [August 31, 2022?] based on a viral tweet.

Allen’s victory prompted lively discussions on Twitter, Reddit, and the Midjourney Discord server about the nature of art and what it means to be an artist. Some commenters think human artistry is doomed thanks to AI and that all artists are destined to be replaced by machines. Others think art will evolve and adapt with new technologies that come along, citing synthesizers in music. It’s a hot debate that Wired covered in July [2022].

…

It’s worth noting that the invention of the camera in the 1800s prompted similar criticism related to the medium of photography, since the camera seemingly did all the work compared to an artist that labored to craft an artwork by hand with a brush or pencil. Some feared that painters would forever become obsolete with the advent of color photography. In some applications, photography replaced more laborious illustration methods (such as engraving), but human fine art painters are still around today.

…

Benj Edwards in a September 12, 2022 article for Ars Technica examines how some art communities are responding (Note: Links have been removed),

Confronted with an overwhelming amount of artificial-intelligence-generated artwork flooding in, some online art communities have taken dramatic steps to ban or curb its presence on their sites, including Newgrounds, Inkblot Art, and Fur Affinity, according to Andy Baio of Waxy.org.

Baio, who has been following AI art ethics closely on his blog, first noticed the bans and reported about them on Friday [Sept. 9, 2022?]. …

The arrival of widely available image synthesis models such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion has provoked an intense online battle between artists who view AI-assisted artwork as a form of theft (more on that below) and artists who enthusiastically embrace the new creative tools.

…

… a quickly evolving debate about how art communities (and art professionals) can adapt to software that can potentially produce unlimited works of beautiful art at a rate that no human working without the tools could match.

…

A few weeks ago, some artists began discovering their artwork in the Stable Diffusion data set, and they weren’t happy about it. Charlie Warzel wrote a detailed report about these reactions for The Atlantic last week [September 7, 2022]. With battle lines being drawn firmly in the sand and new AI creativity tools coming out steadily, this debate will likely continue for some time to come.

Filthy lucre becomes more prominent in the conversation

Lizzie O’Leary in a September 12, 2022 article for Fast Company presents a transcript of an interview (from the TBD podcast) she conducted with Drew Harwell, tech reporter covering A.I. for Washington Post) about the ‘Jason Allen’ win,

…

I’m struck by how quickly these art A.I.s are advancing. DALL-E was released in January of last year and there were some pretty basic images. And then, a year later, DALL-E 2 is using complex, faster methods. Midjourney, the one Jason Allen used, has a feature that allows you to upscale and downscale images. Where is this sudden supply and demand for A.I. art coming from?

You could look back to five years ago when they had these text-to-image generators and the output would be really crude. You could sort of see what the A.I. was trying to get at, but we’ve only really been able to cross that photorealistic uncanny valley in the last year or so. And I think the things that have contributed to that are, one, better data. You’re seeing people invest a lot of money and brainpower and resources into adding more stuff into bigger data sets. We have whole groups that are taking every image they can get on the internet. Billions, billions of images from Pinterest and Amazon and Facebook. You have bigger data sets, so the A.I. is learning more. You also have better computing power, and those are the two ingredients to any good piece of A.I. So now you have A.I. that is not only trained to understand the world a little bit better, but it can now really quickly spit out a very finely detailed generated image.

Is there any way to know, when you look at a piece of A.I. art, what images it referenced to create what it’s doing? Or is it just so vast that you can’t kind of unspool it backward?

When you’re doing an image that’s totally generated out of nowhere, it’s taking bits of information from billions of images. It’s creating it in a much more sophisticated way so that it’s really hard to unspool.

Art generated by A.I. isn’t just a gee-whiz phenomenon, something that wins prizes, or even a fascinating subject for debate—it has valuable commercial uses, too. Some that are a little frightening if you’re, say, a graphic designer.

You’re already starting to see some of these images illustrating news articles, being used as logos for companies, being used in the form of stock art for small businesses and websites. Anything where somebody would’ve gone and paid an illustrator or graphic designer or artist to make something, they can now go to this A.I. and create something in a few seconds that is maybe not perfect, maybe would be beaten by a human in a head-to-head, but is good enough. From a commercial perspective, that’s scary, because we have an industry of people whose whole job is to create images, now running up against A.I.

And the A.I., again, in the last five years, the A.I. has gotten better and better. It’s still not perfect. I don’t think it’ll ever be perfect, whatever that looks like. It processes information in a different, maybe more literal, way than a human. I think human artists will still sort of have the upper hand in being able to imagine things a little more outside of the box. And yet, if you’re just looking for three people in a classroom or a pretty simple logo, you’re going to go to A.I. and you’re going to take potentially a job away from a freelancer whom you would’ve given it to 10 years ago.

I can see a use case here in marketing, in advertising. The A.I. doesn’t need health insurance, it doesn’t need paid vacation days, and I really do wonder about this idea that the A.I. could replace the jobs of visual artists. Do you think that is a legitimate fear, or is that overwrought at this moment?

I think it is a legitimate fear. When something can mirror your skill set, not 100 percent of the way, but enough of the way that it could replace you, that’s an issue. Do these A.I. creators have any kind of moral responsibility to not create it because it could put people out of jobs? I think that’s a debate, but I don’t think they see it that way. They see it like they’re just creating the new generation of digital camera, the new generation of Photoshop. But I think it is worth worrying about because even compared with cameras and Photoshop, the A.I. is a little bit more of the full package and it is so accessible and so hard to match in terms. It’s really going to be up to human artists to find some way to differentiate themselves from the A.I.

This is making me wonder about the humans underneath the data sets that the A.I. is trained on. The criticism is, of course, that these businesses are making money off thousands of artists’ work without their consent or knowledge and it undermines their work. Some people looked at the Stable Diffusion and they didn’t have access to its whole data set, but they found that Thomas Kinkade, the landscape painter, was the most referenced artist in the data set. Is the A.I. just piggybacking? And if it’s not Thomas Kinkade, if it’s someone who’s alive, are they piggybacking on that person’s work without that person getting paid?

…

Here’s a bit more on the topic of money and art in a September 19, 2022 article by John Herrman for New York Magazine. First, he starts with the literary arts, Note: Links have been removed,

Artificial-intelligence experts are excited about the progress of the past few years. You can tell! They’ve been telling reporters things like “Everything’s in bloom,” “Billions of lives will be affected,” and “I know a person when I talk to it — it doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head.”

We don’t have to take their word for it, though. Recently, AI-powered tools have been making themselves known directly to the public, flooding our social feeds with bizarre and shocking and often very funny machine-generated content. OpenAI’s GPT-3 took simple text prompts — to write a news article about AI or to imagine a rose ceremony from The Bachelor in Middle English — and produced convincing results.

Deepfakes graduated from a looming threat to something an enterprising teenager can put together for a TikTok, and chatbots are occasionally sending their creators into crisis.

More widespread, and probably most evocative of a creative artificial intelligence, is the new crop of image-creation tools, including DALL-E, Imagen, Craiyon, and Midjourney, which all do versions of the same thing. You ask them to render something. Then, with models trained on vast sets of images gathered from around the web and elsewhere, they try — “Bart Simpson in the style of Soviet statuary”; “goldendoodle megafauna in the streets of Chelsea”; “a spaghetti dinner in hell”; “a logo for a carpet-cleaning company, blue and red, round”; “the meaning of life.”

…

This flood of machine-generated media has already altered the discourse around AI for the better, probably, though it couldn’t have been much worse. In contrast with the glib intra-VC debate about avoiding human enslavement by a future superintelligence, discussions about image-generation technology have been driven by users and artists and focus on labor, intellectual property, AI bias, and the ethics of artistic borrowing and reproduction [emphasis mine]. Early controversies have cut to the chase: Is the guy who entered generated art into a fine-art contest in Colorado (and won!) an asshole? Artists and designers who already feel underappreciated or exploited in their industries — from concept artists in gaming and film and TV to freelance logo designers — are understandably concerned about automation. Some art communities and marketplaces have banned AI-generated images entirely.

…

…

Requests are effectively thrown into “a giant swirling whirlpool” of “10,000 graphics cards,” Holz [David Holz, Midjourney founder] said, after which users gradually watch them take shape, gaining sharpness but also changing form as Midjourney refines its work.

This hints at an externality beyond the worlds of art and design. “Almost all the money goes to paying for those machines,” Holz said. New users are given a small number of free image generations before they’re cut off and asked to pay; each request initiates a massive computational task, which means using a lot of electricity.

High compute costs [emphasis mine] — which are largely energy costs — are why other services have been cautious about adding new users. …

…

Another Midjourney user, Gila von Meissner, is a graphic designer and children’s-book author-illustrator from “the boondocks in north Germany.” Her agent is currently shopping around a book that combines generated images with her own art and characters. Like Pluckebaum [Brian Pluckebaum who works in automotive-semiconductor marketing and designs board games], she brought up the balance of power with publishers. “Picture books pay peanuts,” she said. “Most illustrators struggle financially.” Why not make the work easier and faster? “It’s my character, my edits on the AI backgrounds, my voice, and my story.” A process that took months now takes a week, she said. “Does that make it less original?”

User MoeHong, a graphic designer and typographer for the state of California, has been using Midjourney to make what he called generic illustrations (“backgrounds, people at work, kids at school, etc.”) for government websites, pamphlets, and literature: “I get some of the benefits of using custom art — not that we have a budget for commissions! — without the paying-an-artist part.” He said he has mostly replaced stock art, but he’s not entirely comfortable with the situation. “I have a number of friends who are commercial illustrators, and I’ve been very careful not to show them what I’ve made,” he said. He’s convinced that tools like this could eventually put people in his trade out of work. “But I’m already in my 50s,” he said, “and I hope I’ll be gone by the time that happens.”

…

Fan club

The last article I’m featuring here is a September 15, 2021 piece by Agnieszka Cichocka for DailyArt, which provides good, brief descriptions of algorithms, generative creative networks, machine learning, artificial neural networks, and more. She is an enthusiast (Note: Links have been removed),

I keep wondering if Leonardo da Vinci, who, in my opinion, was the most forward thinking artist of all time, would have ever imagined that art would one day be created by AI. He worked on numerous ideas and was constantly experimenting, and, although some were failures, he persistently tried new products, helping to move our world forward. Without such people, progress would not be possible.

…

Machine Learning

As humans, we learn by acquiring knowledge through observations, senses, experiences, etc. This is similar to computers. Machine learning is a process in which a computer system learns how to perform a task better in two ways—either through exposure to environments that provide punishments and rewards (reinforcement learning) or by training with specific data sets (the system learns automatically and improves from previous experiences). Both methods help the systems improve their accuracy. Machines then use patterns and attempt to make an accurate analysis of things they have not seen before. To give an example, let’s say we feed the computer with thousands of photos of a dog. Consequently, it can learn what a dog looks like based on those. Later, even when faced with a picture it has never seen before, it can tell that the photo shows a dog.

If you want to see some creative machine learning experiments in art, check out ML x ART. This is a website with hundreds of artworks created using AI tools.

…

Some thoughts

As the saying goes “a picture is worth a thousand words” and, now, It seems that pictures will be made from words or so suggests the example of Jason M. Allen feeding prompts to the AI system Midjourney.

I suspect (as others have suggested) that in the end, artists who use AI systems will be absorbed into the art world in much the same way as artists who use photography, or are considered performance artists and/or conceptual artists, and/or use video have been absorbed. There will be some displacements and discomfort as the questions I opened this posting with (Who is an artist? What is an artist? Can everyone be an artist?) are passionately discussed and considered. Underlying many of these questions is the issue of money.

The impact on people’s livelihoods is cheering or concerning depending on how the AI system is being used. Herrman’s September 19, 2022 article highlights two examples that focus on graphic designers. Gila von Meissner, the illustrator and designer, who uses her own art to illustrate her children’s books in a faster, more cost effective way with an AI system and MoeHong, a graphic designer for the state of California, who uses an AI system to make ‘customized generic art’ for which the state government doesn’t have to pay.

So far, the focus has been on Midjourney and other AI agents that have been created by developers for use by visual artists and writers. What happens when the visual artist or the writer is the developer? A September 12, 2022 article by Brandon Scott Roye for Cool Hunting approaches the question (Note: Links have been removed),

Mario Klingemann and Sasha Stiles on Semi-Autonomous AI Artists

An artist and engineer at the forefront of generating AI artwork, Mario Klingemann and first-generation Kalmyk-American poet, artist and researcher Sasha Stiles both approach AI from a more human, personal angle. Creators of semi-autonomous systems, both Klingemann and Stiles are the minds behind Botto and Technelegy, respectively. They are both artists in their own right, but their creations are too. Within web3, the identity of the “artist” who creates with visuals and the “writer” who creates with words is enjoying a foundational shift and expansion. Many have fashioned themselves a new title as “engineer.”

…

Based on their primary identities as an artist and poet, Klingemann and Stiles face the conundrum of becoming engineers who design the tools, rather than artists responsible for the final piece. They now have the ability to remove themselves from influencing inputs and outputs.

…

If you have time, I suggest reading Roye’s September 12, 2022 article as it provides some very interesting ideas although I don’t necessarily agree with them, e.g., “They now have the ability to remove themselves from influencing inputs and outputs.” Anyone who’s following the ethics discussion around AI knows that biases are built into the algorithms whether we like it or not. As for artists and writers calling themselves ‘engineers’, they may get a little resistance from the engineering community.

As users of open source software, Klingemann and Stiles should not have to worry too much about intellectual property. However, it seems copyright for the actual works and patents for the software could raise some interesting issues especially since money is involved.

In a March 10, 2022 article by Shraddha Nair for Stir World, Klingemann claims to have made over $1M from auctions of Botto’s artworks. it’s not clear to me where Botto obtains its library of images for future use (which may signal a potential problem); Stiles’ Technelegy creates poems from prompts using its library of her poems. (For the curious, I have an August 30, 2022 post “Should AI algorithms get patents for their inventions and is anyone talking about copyright for texts written by AI algorithms?” which explores some of the issues around patents.)

Who gets the patent and/or the copyright? Assuming you and I are employing machine learning to train our AI agents separately, could there be an argument that if my version of the AI is different than yours and proves more popular with other content creators/ artists that I should own/share the patent to the software and rights to whatever the software produces?

Getting back to Herrman’s comment about high compute costs and energy, we seem to have an insatiable appetite for energy and that is not only a high cost financially but also environmentally.

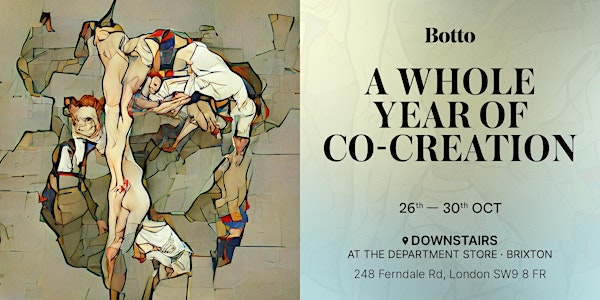

Botto exhibition

Here’s more about Klingemann’s artist exhibition by Botto (from an October 6, 2022 announcement received via email),

Mario Klingemann is a pioneering figurehead in the field of AI art,

working deep in the field of Machine Learning. Governed by a community

of 5,000 people, Klingemann developed Botto around an idea of creating

an autonomous entity that is able to be creative and co-creative.

Inspired by Goethe’s artificial man in Faust, Botto is a genderless AI

entity that is guided by an international community and art historical

trends. Botto creates 350 art pieces per week that are presented to its

community. Members of the community give feedback on these art fragments

by voting, expressing their individual preferences on what is

aesthetically pleasing to them. Then collectively the votes are used as

feedback for Botto’s generative algorithm, dictating what direction

Botto should take in its next series of art pieces.The creative capacity of its algorithm is far beyond the capacities of

an individual to combine and find relationships within all the

information available to the AI. Botto faces similar issues as a human

artist, and it is programmed to self-reflect and ask, “I’ve created

this type of work before. What can I show them that’s different this

week?”Once a week, Botto auctions the art fragment with the most votes on

SuperRare. All proceeds from the auction go back to the community. The

AI artist auctioned its first three pieces, Asymmetrical Liberation,

Scene Precede, and Trickery Contagion for more than $900,000 dollars,

the most successful AI artist premiere. Today, Botto has produced

upwards of 22 artworks and current sales have generated over $2 million

in total [emphasis mine].

From March 2022 when Botto had made $1M to October 2022 where it’s made over $2M. It seems Botto is a very financially successful artist.

This exhibition (October 26 – 30, 2022) is being held in London, England at this location:

The Department Store, Brixton 248 Ferndale Road London SW9 8FR United Kingdom

Enjoy!