A Sept. 23, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily describes some research from Cornell University (US),

Multiferroics — materials that exhibit both magnetic and electric order — are of interest for next-generation computing but difficult to create because the conditions conducive to each of those states are usually mutually exclusive. And in most multiferroics found to date, their respective properties emerge only at extremely low temperatures.

Two years ago, researchers in the labs of Darrell Schlom, the Herbert Fisk Johnson Professor of Industrial Chemistry in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Dan Ralph, the F.R. Newman Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences, in collaboration with professor Ramamoorthy Ramesh at UC Berkeley, published a paper announcing a breakthrough in multiferroics involving the only known material in which magnetism can be controlled by applying an electric field at room temperature: the multiferroic bismuth ferrite.

Schlom’s group has partnered with David Muller and Craig Fennie, professors of applied and engineering physics, to take that research a step further: The researchers have combined two non-multiferroic materials, using the best attributes of both to create a new room-temperature multiferroic.

Their paper, “Atomically engineered ferroic layers yield a room-temperature magnetoelectric multiferroic,” was published — along with a companion News & Views piece — Sept. 22 [2016] in Nature. …

A Sept. 22, 2016 Cornell University news release by Tom Fleischman, which originated the news item, details more about the work (Note: A link has been removed),

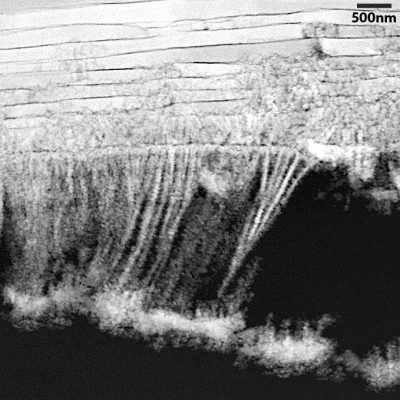

The group engineered thin films of hexagonal lutetium iron oxide (LuFeO3), a material known to be a robust ferroelectric but not strongly magnetic. The LuFeO3 consists of alternating single monolayers of lutetium oxide and iron oxide, and differs from a strong ferrimagnetic oxide (LuFe2O4), which consists of alternating monolayers of lutetium oxide with double monolayers of iron oxide.

The researchers found, however, that they could combine these two materials at the atomic-scale to create a new compound that was not only multiferroic but had better properties that either of the individual constituents. In particular, they found they need to add just one extra monolayer of iron oxide to every 10 atomic repeats of the LuFeO3 to dramatically change the properties of the system.

That precision engineering was done via molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE), a specialty of the Schlom lab. A technique Schlom likens to “atomic spray painting,” MBE let the researchers design and assemble the two different materials in layers, a single atom at a time.

The combination of the two materials produced a strongly ferrimagnetic layer near room temperature. They then tested the new material at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) Advanced Light Source in collaboration with co-author Ramesh to show that the ferrimagnetic atoms followed the alignment of their ferroelectric neighbors when switched by an electric field.

“It was when our collaborators at LBNL demonstrated electrical control of magnetism in the material that we made that things got super exciting,” Schlom said. “Room-temperature multiferroics are exceedingly rare and only multiferroics that enable electrical control of magnetism are relevant to applications.”

In electronics devices, the advantages of multiferroics include their reversible polarization in response to low-power electric fields – as opposed to heat-generating and power-sapping electrical currents – and their ability to hold their polarized state without the need for continuous power. High-performance memory chips make use of ferroelectric or ferromagnetic materials.

“Our work shows that an entirely different mechanism is active in this new material,” Schlom said, “giving us hope for even better – higher-temperature and stronger – multiferroics for the future.”

Collaborators hailed from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the University of Michigan and Penn State University.

Here is a link and a citation to the paper and to a companion piece,

Atomically engineered ferroic layers yield a room-temperature magnetoelectric multiferroic by Julia A. Mundy, Charles M. Brooks, Megan E. Holtz, Jarrett A. Moyer, Hena Das, Alejandro F. Rébola, John T. Heron, James D. Clarkson, Steven M. Disseler, Zhiqi Liu, Alan Farhan, Rainer Held, Robert Hovden, Elliot Padgett, Qingyun Mao, Hanjong Paik, Rajiv Misra, Lena F. Kourkoutis, Elke Arenholz, Andreas Scholl, Julie A. Borchers, William D. Ratcliff, Ramamoorthy Ramesh, Craig J. Fennie, Peter Schiffer et al. Nature 537, 523–527 (22 September 2016) doi:10.1038/nature19343 Published online 21 September 2016

Condensed-matter physics: Multitasking materials from atomic templates by Manfred Fiebig. Nature 537, 499–500 (22 September 2016) doi:10.1038/537499a Published online 21 September 2016

Both the paper and its companion piece are behind a paywall.