Researchers at the University of Ottawa have debunked a myth, one involving metals and light according to a March 1i, 2021 news item on phys.org (Note: Links have been removed),

Researchers at the University of Ottawa have debunked the decade-old myth of metals being useless in photonics—the science and technology of light—with their findings, recently published in Nature Communications, expected to lead to many applications in the field of nanophotonics.

“We broke the record for the resonance quality factor (Q-factor) of a periodic array of metal nanoparticles by one order of magnitude compared to previous reports,” said senior author Dr. Ksenia Dolgaleva, Canada Research Chair in Integrated Photonics (Tier 2) and Associate Professor in the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) at the University of Ottawa.

…

A March 18, 2021 University of Ottawa news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, introduced me to the word ‘lossy’ and discussed the decade-long myth in more detail,

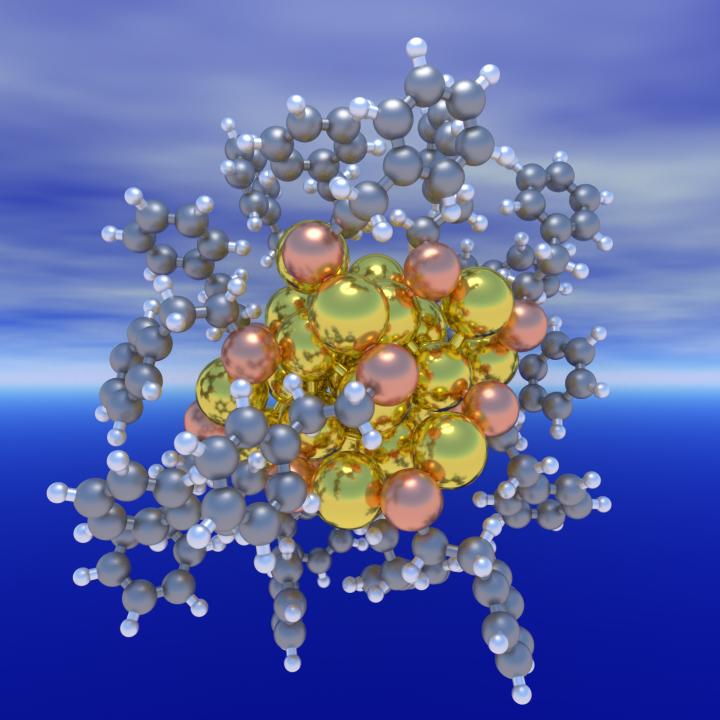

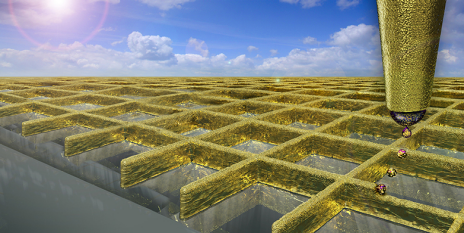

“It is a well-known fact that metals are very lossy when they interact with light, which means they cause the dissipation of electrical energy. The high losses compromise their use in optics and photonics. We demonstrated ultra-high-Q resonances in a metasurface (an artificially structured surface) comprised of an array of metal nanoparticles embedded inside a flat glass substrate. These resonances can be used for efficient light manipulating and enhanced light-matter interaction, showing metals are useful in photonics.”

“In previous works, researchers attempted to mitigate the adverse effect of losses to access favorable properties of metal nanoparticle arrays,” observed the co-lead author of the study Md Saad Bin-Alam, a uOttawa doctoral student in EECS.

“However, their attempts did not provide a significant improvement in the quality factors of the resonances of the arrays. We implemented a combination of techniques rather than a single approach and obtained an order-of-magnitude improvement demonstrating a metal nanoparticle array (metasurface) with a record-high quality factor.”

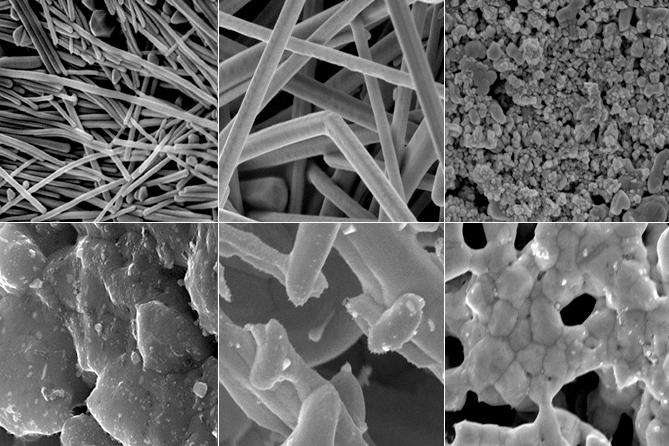

According to the researchers, structured surfaces – also called metasurfaces – have very promising prospects in a variety of nanophotonic applications that can never be explored using traditional natural bulk materials. Sensors, nanolasers, light beam shaping and steering are just a few examples of the many applications.

“Metasurfaces made of noble metal nanoparticles – gold or silver for instance – possess some unique benefits over non-metallic nanoparticles. They can confine and control light in a nanoscale volume that is less than one quarter of the wavelength of light (less than 100 nm, while the width of a hair is over 10 000 nm),” explained Md Saad Bin-Alam.

“Interestingly, unlike in non-metallic nanoparticles, the light is not confined or trapped inside the metal nanoparticles but is concentrated close to their surface. This phenomenon is scientifically called ‘localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs)’. This feature gives a great superiority to metal nanoparticles compared to their dielectric counterparts, because one could exploit such surface resonances to detect bio-organisms or molecules in medicine or chemistry. Also, such surface resonances could be used as the feedback mechanism necessary for laser gain. In such a way, one can realize a nanoscale tiny laser that can be adopted in many future nanophotonic applications, like light detection and ranging (LiDAR) for the far-field object detection.”

According to the researchers, the efficiency of these applications depends on the resonant Q-factors.

“Unfortunately, due to the high ‘absorptive’ and ‘radiative’ loss in metal nanoparticles, the LSPRs Q-factors are very low,” said co-lead author Dr. Orad Reshef, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics at the University of Ottawa.

“More than a decade ago, researchers found a way to mitigate the dissipative loss by carefully arranging the nanoparticles in a lattice. From such ‘surface lattice’ manipulation, a new ‘surface lattice resonance (SLR)’ emerges with suppressed losses. Until our work, the maximum Q-factors reported in SLRs was around a few hundred. Although such early reported SLRs were better than the low-Q LSPRs, they were still not very impressive for efficient applications. It led to the myth that metals are not useful for practical applications.”

A myth that the group was able to deconstruct during its work at the University of Ottawa’s Advanced Research Complex between 2017 and 2020.

“At first, we performed numerical modelling of a gold nanoparticle metasurface and were surprised to obtain quality factors of several thousand,” said Md Saad Bin-Alam, who primarily designed the metasurface structure.

“This value has never been reported experimentally, and we decided to analyze why and to attempt an experimental demonstration of such a high Q. We observed a very high-Q SLR of value nearly 2400, that is at least 10 times larger than the largest SLRs Q reported earlier.”

A discovery that made them realize that there’s still a lot to learn about metals.

“Our research proved that we are still far from knowing all the hidden mysteries of metal (plasmonic) nanostructures,” concluded Dr. Orad Reshef, who fabricated the metasurface sample. “Our work has debunked a decade-long myth that such structures are not suitable for real-life optical applications due to the high losses. We demonstrated that, by properly engineering the nanostructure and carefully conducting an experiment, one can improve the result significantly.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ultra-high-Q resonances in plasmonic metasurfaces by M. Saad Bin-Alam, Orad Reshef, Yaryna Mamchur, M. Zahirul Alam, Graham Carlow, Jeremy Upham, Brian T. Sullivan, Jean-Michel Ménard, Mikko J. Huttunen, Robert W. Boyd & Ksenia Dolgaleva. Nature Communications volume 12, Article number: 974 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21196-2 Published 12 February 2021

This paper is open access.

![[downloaded from https://github.com/jhermann/Stack-O-Waffles] Credit: jherman](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Waffles.png)