There’s some interesting work on invisibility cloaks coming from the University of Texas at Austin according to a July 6, 2015 news item on Nanowerk,

Researchers in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin have been able to quantify fundamental physical limitations on the performance of cloaking devices, a technology that allows objects to become invisible or undetectable to electromagnetic waves including radio waves, microwaves, infrared and visible light.

A July 5, 2016 University of Texas at Austin news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

The researchers’ theory confirms that it is possible to use cloaks to perfectly hide an object for a specific wavelength, but hiding an object from an illumination containing different wavelengths becomes more challenging as the size of the object increases.

Andrea Alù, an electrical and computer engineering professor and a leading researcher in the area of cloaking technology, along with graduate student Francesco Monticone, created a quantitative framework that now establishes boundaries on the bandwidth capabilities of electromagnetic cloaks for objects of different sizes and composition. As a result, researchers can calculate the expected optimal performance of invisibility devices before designing and developing a specific cloak for an object of interest. …

Cloaks are made from artificial materials, called metamaterials, that have special properties enabling a better control of the incoming wave, and can make an object invisible or transparent. The newly established boundaries apply to cloaks made of passive metamaterials — those that do not draw energy from an external power source.

Understanding the bandwidth and size limitations of cloaking is important to assess the potential of cloaking devices for real-world applications such as communication antennas, biomedical devices and military radars, Alù said. The researchers’ framework shows that the performance of a passive cloak is largely determined by the size of the object to be hidden compared with the wavelength of the incoming wave, and it quantifies how, for shorter wavelengths, cloaking gets drastically more difficult.

For example, it is possible to cloak a medium-size antenna from radio waves over relatively broad bandwidths for clearer communications, but it is essentially impossible to cloak large objects, such as a human body or a military tank, from visible light waves, which are much shorter than radio waves.

“We have shown that it will not be possible to drastically suppress the light scattering of a tank or an airplane for visible frequencies with currently available techniques based on passive materials,” Monticone said. “But for objects comparable in size to the wavelength that excites them (a typical radio-wave antenna, for example, or the tip of some optical microscopy tools), the derived bounds show that you can do something useful, the restrictions become looser, and we can quantify them.”

In addition to providing a practical guide for research on cloaking devices, the researchers believe that the proposed framework can help dispel some of the myths that have been developed around cloaking and its potential to make large objects invisible.

“The question is, ‘Can we make a passive cloak that makes human-scale objects invisible?’ ” Alù said. “It turns out that there are stringent constraints in coating an object with a passive material and making it look as if the object were not there, for an arbitrary incoming wave and observation point.”Now that bandwidth limits on cloaking are available, researchers can focus on developing practical applications with this technology that get close to these limits.

“If we want to go beyond the performance of passive cloaks, there are other options,” Monticone said. “Our group and others have been exploring active and nonlinear cloaking techniques, for which these limits do not apply. Alternatively, we can aim for looser forms of invisibility, as in cloaking devices that introduce phase delays as light is transmitted through, camouflaging techniques, or other optical tricks that give the impression of transparency, without actually reducing the overall scattering of light.”

Alù’s lab is working on the design of active cloaks that use metamaterials plugged to an external energy source to achieve broader transparency bandwidths.

“Even with active cloaks, Einstein’s theory of relativity fundamentally limits the ultimate performance for invisibility,” Alù said. “Yet, with new concepts and designs, such as active and nonlinear metamaterials, it is possible to move forward in the quest for transparency and invisibility.”

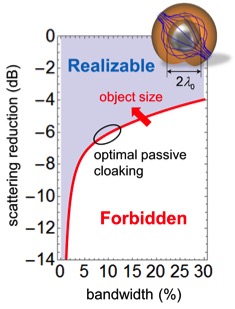

The researchers have prepared a diagram illustrating their work,

The graph shows the trade-off between how much an object can be made transparent (scattering reduction; vertical axis) and the color span (bandwidth; horizontal axis) over which this phenomenon can be achieved. Courtesy: University of Texas at Austin

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Invisibility exposed: physical bounds on passive cloaking by Francesco Monticone and Andrea Alù. Optica Vol. 3, Issue 7, pp. 718-724 (2016) •doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000718

This paper is open access.