I’m quite intrigued by this ‘jell-o’ story. It’s hard to believe a childhood dessert might prove to have an application as a catalyst for producing hydrogen fuel. From a December 14, 2018 news item on Nanowerk,

A cheap and effective new catalyst developed by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, can generate hydrogen fuel from water just as efficiently as platinum, currently the best — but also most expensive — water-splitting catalyst out there.

The catalyst, which is composed of nanometer-thin sheets of metal carbide, is manufactured using a self-assembly process that relies on a surprising ingredient: gelatin, the material that gives Jell-O its jiggle.

A December 13, 2018 University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley) news release by Kara Manke (also on EurekAlert but published on Dec. 14, 2018), which originated the news item, provides more technical detail,

“Platinum is expensive, so it would be desirable to find other alternative materials to replace it,” said senior author Liwei Lin, professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley. “We are actually using something similar to the Jell-O that you can eat as the foundation, and mixing it with some of the abundant earth elements to create an inexpensive new material for important catalytic reactions.”

The work appears in the Dec. 13 [2018] print edition of the journal Advanced Materials.

A zap of electricity can break apart the strong bonds that tie water molecules together, creating oxygen and hydrogen gas, the latter of which is an extremely valuable source of energy for powering hydrogen fuel cells. Hydrogen gas can also be used to help store energy from renewable yet intermittent energy sources like solar and wind power, which produce excess electricity when the sun shines or when the wind blows, but which go dormant on rainy or calm days.

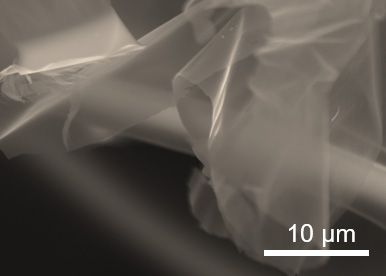

When magnified, the two-dimensional metal carbides resemble sheets of cell[o]phane. (Xining Zang photo, copyright Wiley)

But simply sticking an electrode in a glass of water is an extremely inefficient method of generating hydrogen gas. For the past 20 years, scientists have been searching for catalysts that can speed up this reaction, making it practical for large-scale use.

“The traditional way of using water gas to generate hydrogen still dominates in industry. However, this method produces carbon dioxide as byproduct,” said first author Xining Zang, who conducted the research as a graduate student in mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley. “Electrocatalytic hydrogen generation is growing in the past decade, following the global demand to lower emissions. Developing a highly efficient and low-cost catalyst for electrohydrolysis will bring profound technical, economical and societal benefit.”

To create the catalyst, the researchers followed a recipe nearly as simple as making Jell-O from a box. They mixed gelatin and a metal ion — either molybdenum, tungsten or cobalt — with water, and then let the mixture dry.

“We believe that as gelatin dries, it self-assembles layer by layer,” Lin said. “The metal ion is carried by the gelatin, so when the gelatin self-assembles, your metal ion is also arranged into these flat layers, and these flat sheets are what give Jell-O its characteristic mirror-like surface.”

Heating the mixture to 600 degrees Celsius triggers the metal ion to react with the carbon atoms in the gelatin, forming large, nanometer-thin sheets of metal carbide. The unreacted gelatin burns away.

The researchers tested the efficiency of the catalysts by placing them in water and running an electric current through them. When stacked up against each other, molybdenum carbide split water the most efficiently, followed by tungsten carbide and then cobalt carbide, which didn’t form thin layers as well as the other two. Mixing molybdenum ions with a small amount of cobalt boosted the performance even more.

“It is possible that other forms of carbide may provide even better performance,” Lin said.

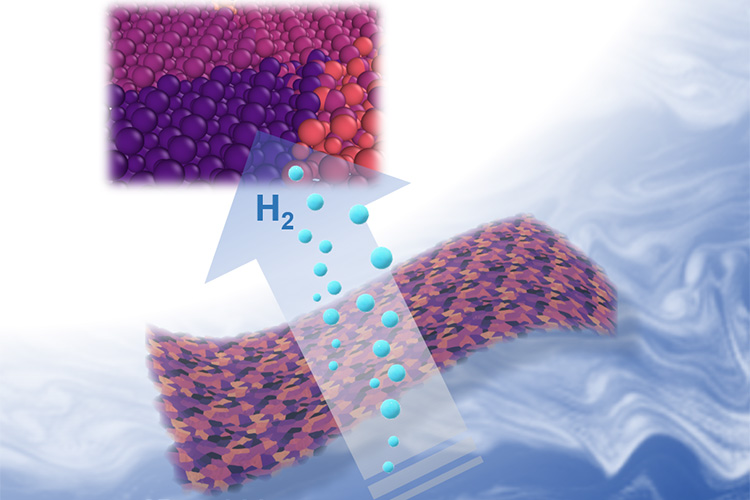

Molecules in gelatin naturally self-assemble in flat sheets, carrying the metal ions with them (left). Heating the mixture to 600 degrees Celsius burns off the gelatin, leaving nanometer-thin sheets of metal carbide. (Xining Zang illustration, copyright Wiley)

The two-dimensional shape of the catalyst is one of the reasons why it is so successful. That is because the water has to be in contact with the surface of the catalyst in order to do its job, and the large surface area of the sheets mean that the metal carbides are extremely efficient for their weight.

Because the recipe is so simple, it could easily be scaled up to produce large quantities of the catalyst, the researchers say.

“We found that the performance is very close to the best catalyst made of platinum and carbon, which is the gold standard in this area,” Lin said. “This means that we can replace the very expensive platinum with our material, which is made in a very scalable manufacturing process.”

Co-authors on the study are Lujie Yang, Buxuan Li and Minsong Wei of UC Berkeley, J. Nathan Hohman and Chenhui Zhu of Lawrence Berkeley National Lab; Wenshu Chen and Jiajun Gu of Shanghai Jiao Tong University; Xiaolong Zou and Jiaming Liang of the Shenzhen Institute; and Mohan Sanghasadasa of the U.S. Army RDECOM AMRDEC.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Self‐Assembly of Large‐Area 2D Polycrystalline Transition Metal Carbides for Hydrogen Electrocatalysis by Xining Zang, Wenshu Chen, Xiaolong Zou, J. Nathan Hohman, Lujie Yang

Buxuan Li, Minsong Wei, Chenhui Zhu, Jiaming Liang, Mohan Sanghadasa, Jiajun Gu, Liwei Lin. Advanced Materials Volume30, Issue 50 December 13, 2018 1805188 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201805188 First published [online]: 09 October 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.