A March 15, 2022 news item on Nanowerk suggests that nanoplastics should be regulated,

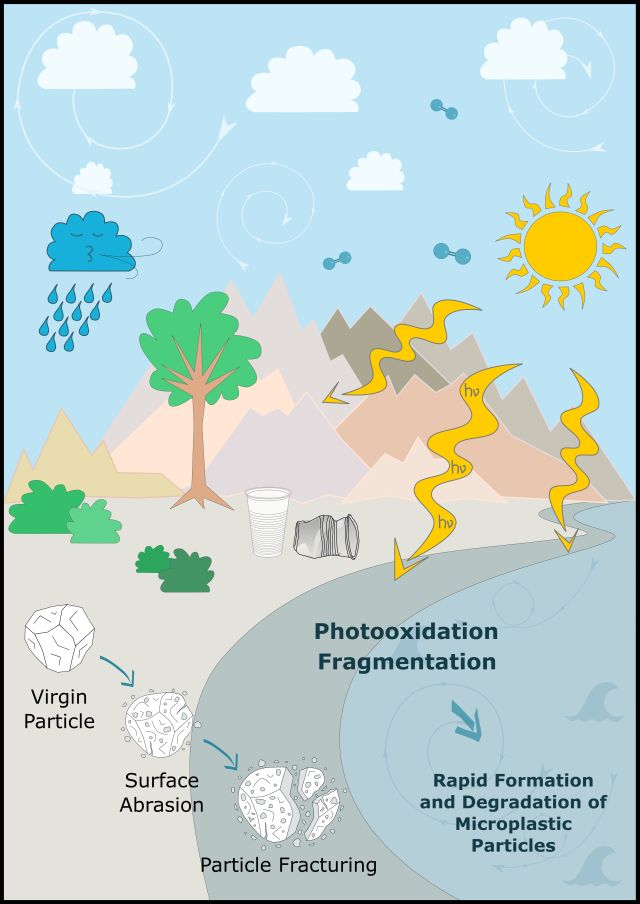

The regulation of plastics has emerged as a significant science-policy challenge, initiated by growing societal concerns regarding plastic pollution. A specific focus is now on nanoplastics, i.e., plastic particles smaller than 1000 nanometres in size. The need to include nanoplastics in existing regulatory frameworks arises from the increasing number of studies demonstrating the bioavailability and harmfulness of smaller plastic particles, compared to larger fragments of plastic.

…

This regulatory initiative is taking place in Europe, from a March 15, 2022 University of Eastern Finland press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item,

Currently, three important policy and legislative processes are on-going in parallel that will impact the future regulation of plastics in general, and of intentionally produced micro- and nanoplastics in particular. Firstly, the European Commission is considering the restriction proposal commissioned by the European Chemicals Agency on intentionally added microplastics. Secondly, there is a discussion about how to define polymers under the European Chemicals Regulation, REACH, so that polymers are not automatically exempted from registration and submission of health and environmental safety information. Thirdly, the European Commission is in the process of revising its proposed definition of nanomaterials.

In a viewpoint article published in Environmental Science & Technology yesterday [published online March 14, 2022],researchers address regulatory concerns related to intentionally produced nanoplastics and outline how the inclusion of the three above-mentioned policy and legislative processes could impact the future regulation of nanoplastics. The discussion in the paper is about whether nanoplastics could be classified as microplastics, nanomaterials, or polymers for regulatory purposes.

According to the researchers, there is no credible scientific reason not to include nanoplastics in existing regulations as they meet all the criteria of chemicals and nanomaterials. Emerging knowledge on the harmfulness of nanoplastics is a strong motivation for including intentionally produced nanoplastics in relevant regulations, as particle-specific hazards may be relevant.

The researchers point out that since molecular weight and particle size are inter-convertible, it doesn’t matter which parameter is chosen as the basis for regulation. However, given the huge effort that has already gone into shaping REACH for nanomaterials, the practical approach would be to include nanoplastics in the regulation of nanomaterials.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Can Current Regulations Account for Intentionally Produced Nanoplastics? by Fazel Abdolahpur Monikh, Steffen Foss Hansen, Martina G. Vijver, Esther Kentin, Maria Bille Nielsen, Anders Baun, Kristian Syberg, Iseult Lynch, Eugenia Valsami-Jones, and Willie J.G.M. Peijnenburg. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c00965 Publication Date:March 14, 2022 © 2022 American Chemical Society

This paper appears to be open access.