For some reason it took a lot longer than usual to find this research paper despite having the journal (Nature Communications), the title (Spontaneous formation …), and the authors’ names. Thankfully, success was wrested from the jaws of defeat (I don’t care if that is trite; it’s how I felt) and links, etc. follow at the end as usual.

An April 19, 2018 Stanford University news release (also on EurekAlert) spins fascinating tale,

An experiment that, by design, was not supposed to turn up anything of note instead produced a “bewildering” surprise, according to the Stanford scientists who made the discovery: a new way of creating gold nanoparticles and nanowires using water droplets.

The technique, detailed April 19 [2018] in the journal Nature Communications, is the latest discovery in the new field of on-droplet chemistry and could lead to more environmentally friendly ways to produce nanoparticles of gold and other metals, said study leader Richard Zare, a chemist in the School of Humanities and Sciences and a co-founder of Stanford Bio-X.

“Being able to do reactions in water means you don’t have to worry about contamination. It’s green chemistry,” said Zare, who is the Marguerite Blake Wilbur Professor in Natural Science at Stanford.

Noble metal

Gold is known as a noble metal because it is relatively unreactive. Unlike base metals such as nickel and copper, gold is resistant to corrosion and oxidation, which is one reason it is such a popular metal for jewelry.

Around the mid-1980s, however, scientists discovered that gold’s chemical aloofness only manifests at large, or macroscopic, scales. At the nanometer scale, gold particles are very chemically reactive and make excellent catalysts. Today, gold nanostructures have found a role in a wide variety of applications, including bio-imaging, drug delivery, toxic gas detection and biosensors.

Until now, however, the only reliable way to make gold nanoparticles was to combine the gold precursor chloroauric acid with a reducing agent such as sodium borohydride.

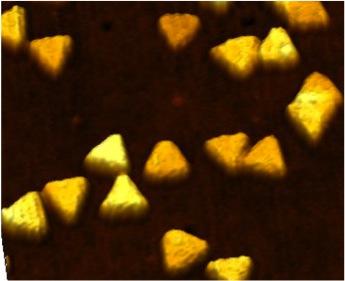

The reaction transfers electrons from the reducing agent to the chloroauric acid, liberating gold atoms in the process. Depending on how the gold atoms then clump together, they can form nano-size beads, wires, rods, prisms and more.

A spritz of gold

Recently, Zare and his colleagues wondered whether this gold-producing reaction would proceed any differently with tiny, micron-size droplets of chloroauric acid and sodium borohydide. How large is a microdroplet? “It is like squeezing a perfume bottle and out spritzes a mist of microdroplets,” Zare said.

From previous experiments, the scientists knew that some chemical reactions proceed much faster in microdroplets than in larger solution volumes.

Indeed, the team observed that gold nanoparticle grew over 100,000 times faster in microdroplets. However, the most striking observation came while running a control experiment in which they replaced the reducing agent – which ordinarily releases the gold particles – with microdroplets of water.

“Much to our bewilderment, we found that gold nanostructures could be made without any added reducing agents,” said study first author Jae Kyoo Lee, a research associate.

Viewed under an electron microscope, the gold nanoparticles and nanowires appear fused together like berry clusters on a branch.

The surprise finding means that pure water microdroplets can serve as microreactors for the production of gold nanostructures. “This is yet more evidence that reactions in water droplets can be fundamentally different from those in bulk water,” said study coauthor Devleena Samanta, a former graduate student in Zare’s lab and co-author on the paper.

If the process can be scaled up, it could eliminate the need for potentially toxic reducing agents that have harmful health side effects or that can pollute waterways, Zare said.

It’s still unclear why water microdroplets are able to replace a reducing agent in this reaction. One possibility is that transforming the water into microdroplets greatly increases its surface area, creating the opportunity for a strong electric field to form at the air-water interface, which may promote the formation of gold nanoparticles and nanowires.

“The surface area atop a one-liter beaker of water is less than one square meter. But if you turn the water in that beaker into microdroplets, you will get about 3,000 square meters of surface area – about the size of half a football field,” Zare said.

The team is exploring ways to utilize the nanostructures for various catalytic and biomedical applications and to refine their technique to create gold films.

“We observed a network of nanowires that may allow the formation of a thin layer of nanowires,” Samanta said.

Here’s a link and a citation for the paper,

Spontaneous formation of gold nanostructures in aqueous microdroplets by Jae Kyoo Lee, Devleena Samanta, Hong Gil Nam, & Richard N. Zare. Nature Communicationsvolume 9, Article number: 1562 (2018) doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04023-z Published online: 19 April 2018

Not unsurprisingly given Zare’s history as recounted in the news release, this paper is open access.