It’s been a while since I’ve featured anything from Purdue University (Indiana, US). From a November 7, 2023 news item on Nanowerk, Note Links have been removed,

Technology is edging closer and closer to the super-speed world of computing with artificial intelligence. But is the world equipped with the proper hardware to be able to handle the workload of new AI technological breakthroughs?

Key Takeaways

Current AI technologies are strained by the limitations of silicon-based computing hardware, necessitating new solutions.Research led by Erica Carlson [Purdue University] suggests that neuromorphic [brainlike] architectures, which replicate the brain’s neurons and synapses, could revolutionize computing efficiency and power.

Vanadium oxides have been identified as a promising material for creating artificial neurons and synapses, crucial for neuromorphic computing.

Innovative non-volatile memory, observed in vanadium oxides, could be the key to more energy-efficient and capable AI hardware.

Future research will explore how to optimize the synaptic behavior of neuromorphic materials by controlling their memory properties.

…

An October 13, 2023 Purdue University news release (also on EurekAlert but published November 6, 2023) by Cheryl Pierce, which originated the news item, provides more detail about the work, Note: A link has been removed,

“The brain-inspired codes of the AI revolution are largely being run on conventional silicon computer architectures which were not designed for it,” explains Erica Carlson, 150th Anniversary Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Purdue University.

A joint effort between Physicists from Purdue University, University of California San Diego (USCD) and École Supérieure de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles (ESPCI) in Paris, France, believe they may have discovered a way to rework the hardware…. [sic] By mimicking the synapses of the human brain. They published their findings, “Spatially Distributed Ramp Reversal Memory in VO2” in Advanced Electronic Materials which is featured on the back cover of the October 2023 edition.

New paradigms in hardware will be necessary to handle the complexity of tomorrow’s computational advances. According to Carlson, lead theoretical scientist of this research, “neuromorphic architectures hold promise for lower energy consumption processors, enhanced computation, fundamentally different computational modes, native learning and enhanced pattern recognition.”

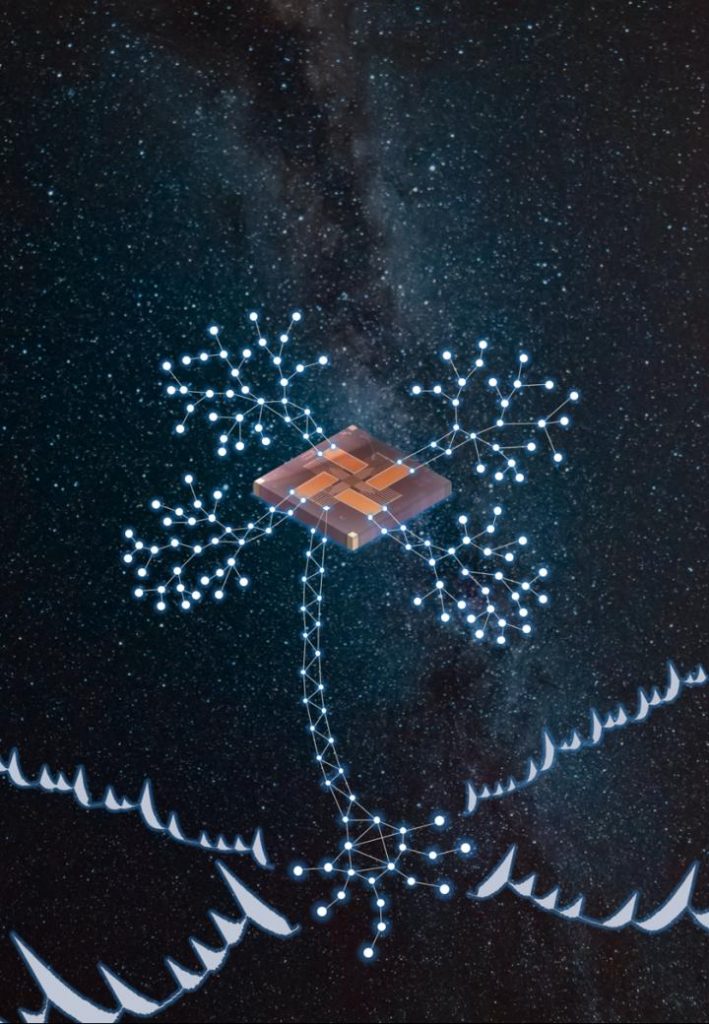

Neuromorphic architecture basically boils down to computer chips mimicking brain behavior. Neurons are cells in the brain that transmit information. Neurons have small gaps at their ends that allow signals to pass from one neuron to the next which are called synapses. In biological brains, these synapses encode memory. This team of scientists concludes that vanadium oxides show tremendous promise for neuromorphic computing because they can be used to make both artificial neurons and synapses.

“The dissonance between hardware and software is the origin of the enormously high energy cost of training, for example, large language models like ChatGPT,” explains Carlson. “By contrast, neuromorphic architectures hold promise for lower energy consumption by mimicking the basic components of a brain: neurons and synapses. Whereas silicon is good at memory storage, the material does not easily lend itself to neuron-like behavior. Ultimately, to provide efficient, feasible neuromorphic hardware solutions requires research into materials with radically different behavior from silicon – ones that can naturally mimic synapses and neurons. Unfortunately, the competing design needs of artificial synapses and neurons mean that most materials that make good synaptors fail as neuristors, and vice versa. Only a handful of materials, most of them quantum materials, have the demonstrated ability to do both.”

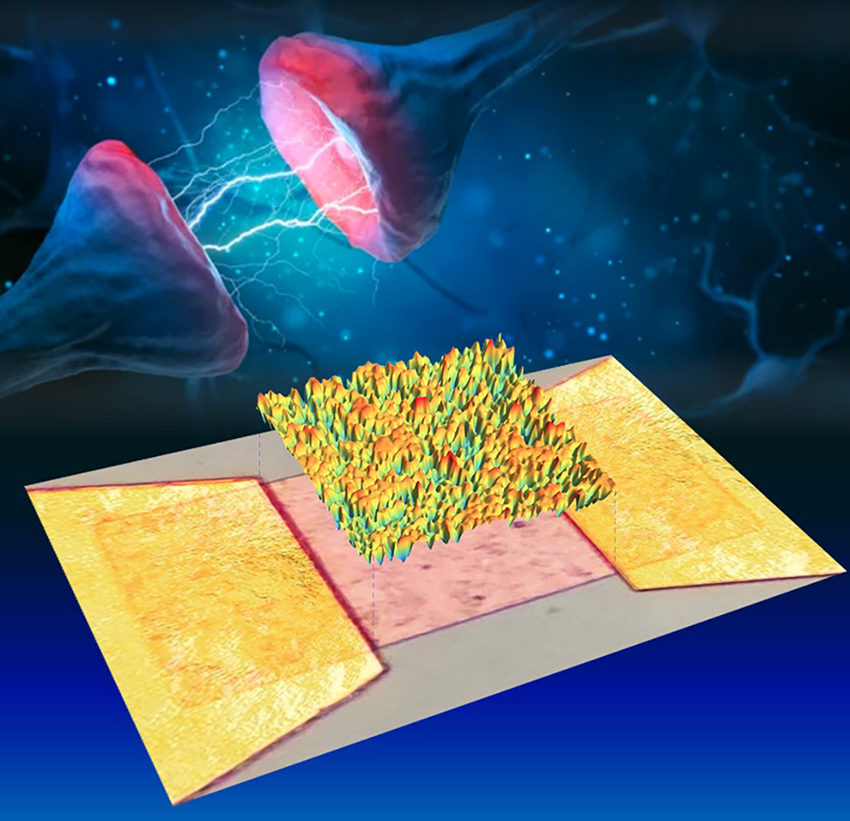

The team relied on a recently discovered type of non-volatile memory which is driven by repeated partial temperature cycling through the insulator-to-metal transition. This memory was discovered in vanadium oxides.

Alexandre Zimmers, lead experimental scientist from Sorbonne University and École Supérieure de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles, Paris, explains, “Only a few quantum materials are good candidates for future neuromorphic devices, i.e., mimicking artificial synapses and neurons. For the first time, in one of them, vanadium dioxide, we can see optically what is changing in the material as it operates as an artificial synapse. We find that memory accumulates throughout the entirety of the sample, opening new opportunities on how and where to control this property.”

“The microscopic videos show that, surprisingly, the repeated advance and retreat of metal and insulator domains causes memory to be accumulated throughout the entirety of the sample, rather than only at the boundaries of domains,” explains Carlson. “The memory appears as shifts in the local temperature at which the material transitions from insulator to metal upon heating, or from metal to insulator upon cooling. We propose that these changes in the local transition temperature accumulate due to the preferential diffusion of point defects into the metallic domains that are interwoven through the insulator as the material is cycled partway through the transition.”

Now that the team has established that vanadium oxides are possible candidates for future neuromorphic devices, they plan to move forward in the next phase of their research.

“Now that we have established a way to see inside this neuromorphic material, we can locally tweak and observe the effects of, for example, ion bombardment on the material’s surface,” explains Zimmers. “This could allow us to guide the electrical current through specific regions in the sample where the memory effect is at its maximum. This has the potential to significantly enhance the synaptic behavior of this neuromorphic material.”

There’s a very interesting 16 mins. 52 secs. video embedded in the October 13, 2023 Purdue University news release. In an interview with Dr. Erica Carlson who hosts The Quantum Age website and video interviews on its YouTube Channel, Alexandre Zimmers takes you from an amusing phenomenon observed by 19th century scientists through the 20th century where it becomes of more interest as the nanscale phenonenon can be exploited (sonar, scanning tunneling microscopes, singing birthday cards, etc.) to the 21st century where we are integrating this new information into a quantum* material for neuromorphic hardware.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Spatially Distributed Ramp Reversal Memory in VO2 by Sayan Basak, Yuxin Sun, Melissa Alzate Banguero, Pavel Salev, Ivan K. Schuller, Lionel Aigouy, Erica W. Carlson, Alexandre Zimmers. Advanced Electronic Materials Volume 9, Issue 10 October 2023 2300085 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202300085 First published: 10 July 2023

This paper is open access.

There’s a lot of research into neuromorphic hardware, here’s a sampling of some of my most recent posts on the topic,

- October 12, 2023 posting, IBM’s neuromorphic chip, a prototype and more

- June 23, 2023 posting, Neuromorphic engineering: an overview

- August 26, 2022 posting, Save energy with neuromorphic (brainlike) hardware

- August 23, 2022 posting, Neuromorphic hardware could yield computational advantages for more than just artificial intelligence

- January 26, 2022 posting, Highly scalable neuromorphic (brainlike) computing hardware

There’s more, just use ‘neuromorphic hardware’ for your search term.

*’meta’ changed to ‘quantum’ on January 8, 2024.