A Jan. 6, 2015 news item on Nanowerk features a proposal by US scientists for a Unified Microbiome Initiative (UMI),

In October [2015], an interdisciplinary group of scientists proposed forming a Unified Microbiome Initiative (UMI) to explore the world of microorganisms that are central to life on Earth and yet largely remain a mystery.

An article in the journal ACS Nano (“Tools for the Microbiome: Nano and Beyond”) describes the tools scientists will need to understand how microbes interact with each other and with us.

A Jan. 6, 2016 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

Microbes live just about everywhere: in the oceans, in the soil, in the atmosphere, in forests and in and on our bodies. Research has demonstrated that their influence ranges widely and profoundly, from affecting human health to the climate. But scientists don’t have the necessary tools to characterize communities of microbes, called microbiomes, and how they function. Rob Knight, Jeff F. Miller, Paul S. Weiss and colleagues detail what these technological needs are.

The researchers are seeking the development of advanced tools in bioinformatics, high-resolution imaging, and the sequencing of microbial macromolecules and metabolites. They say that such technology would enable scientists to gain a deeper understanding of microbiomes. Armed with new knowledge, they could then tackle related medical and other challenges with greater agility than what is possible today.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Tools for the Microbiome: Nano and Beyond by Julie S. Biteen, Paul C. Blainey, Zoe G. Cardon, Miyoung Chun, George M. Church, Pieter C. Dorrestein, Scott E. Fraser, Jack A. Gilbert, Janet K. Jansson, Rob Knight, Jeff F. Miller, Aydogan Ozcan, Kimberly A. Prather, Stephen R. Quake, Edward G. Ruby, Pamela A. Silver, Sharif Taha, Ger van den Engh, Paul S. Weiss, Gerard C. L. Wong, Aaron T. Wright, and Thomas D. Young. ACS Nano, Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07826 Publication Date (Web): December 22, 2015

Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society

This is an open access paper.

I sped through very quickly and found a couple of references to ‘nano’,

Ocean Microbiomes and Nanobiomes

Life in the oceans is supported by a community of extremely small organisms that can be called a “nanobiome.” These nanoplankton particles, many of which measure less than 0.001× the volume of a white blood cell, harvest solar and chemical energy and channel essential elements into the food chain. A deep network of larger life forms (humans included) depends on these tiny microbes for its energy and chemical building blocks.

The importance of the oceanic nanobiome has only recently begun to be fully appreciated. Two dominant forms, Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, were not discovered until the 1980s and 1990s.(32-34) Prochloroccus has now been demonstrated to be so abundant that it may account for as much as 10% of the world’s living organic carbon. The organism divides on a diel cycle while maintaining constant numbers, suggesting that about 5% of the world’s biomass flows through this species on a daily basis.(35-37)

Metagenomic studies show that many other less abundant life forms must exist but elude direct observation because they can neither be isolated nor grown in culture.

The small sizes of these organisms (and their genomes) indicate that they are highly specialized and optimized. Metagenome data indicate a large metabolic heterogeneity within the nanobiome. Rather than combining all life functions into a single organism, the nanobiome works as a network of specialists that can only exist as a community, therein explaining their resistance to being cultured. The detailed composition of the network is the result of interactions between the organisms themselves and the local physical and chemical environment. There is thus far little insight into how these networks are formed and how they maintain steady-state conditions in the turbulent natural ocean environment.

Rather than combining all life functions into a single organism, the nanobiome works as a network of specialists that can only exist as a community

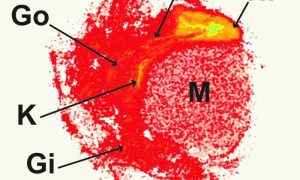

The serendipitous discovery of Prochlorococcus happened by applying flow cytometry (developed as a medical technique for counting blood cells) to seawater.(34) With these medical instruments, the faint signals from nanoplankton can only be seen with great difficulty against noisy backgrounds. Currently, a small team is adapting flow cytometric technology to improve the capabilities for analyzing individual nanoplankton particles. The latest generation of flow cytometers enables researchers to count and to make quantitative observations of most of the small life forms (including some viruses) that comprise the nanobiome. To our knowledge, there are only two well-equipped mobile flow cytometry laboratories that are regularly taken to sea for real-time observations of the nanobiome. The laboratories include equipment for (meta)genome analysis and equipment to correlate the observations with the local physical parameters and (nutrient) chemistry in the ocean. Ultimately, integration of these measurements will be essential for understanding the complexity of the oceanic microbiome.

The ocean is tremendously undersampled. Ship time is costly and limited. Ultimately, inexpensive, automated, mobile biome observatories will require methods that integrate microbiome and nanobiome measurements, with (meta-) genomics analyses, with local geophysical and geochemical parameters.(38-42) To appreciate how the individual components of the ocean biome are related and work together, a more complete picture must be established.

The marine environment consists of stratified zones, each with a unique, characteristic biome.(43) The sunlit waters near the surface are mixed by wind action. Deeper waters may be mixed only occasionally by passing storms. The dark deepest layers are stabilized by temperature/salinity density gradients. Organic material from the photosynthetically active surface descends into the deep zone, where it decomposes into nutrients that are mixed with compounds that are released by volcanic and seismic action. These nutrients diffuse upward to replenish the depleted surface waters. The biome is stratified accordingly, sometimes with sudden transitions on small scales. Photo-autotrophs dominate near the surface. Chemo-heterotrophs populate the deep. The makeup of the microbial assemblages is dictated by the local nutrient and oxygen concentrations. The spatiotemporal interplay of these systems is highly relevant to such issues as the carbon budget of the planet but remains little understood.

And then, there was this,

Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Opportunities

The great advantage of nanoscience and nanotechnology in studying microbiomes is that the nanoscale is the scale of function in biology. It is this convergence of scales at which we can “see” and at which we can fabricate that heralds the contributions that can be made by developing new nanoscale analysis tools.(159-168) Microbiomes operate from the nanoscale up to much larger scales, even kilometers, so crossing these scales will pose significant challenges to the field, in terms of measurement, stimulation/response, informatics, and ultimately understanding.

Some progress has been made in creating model systems(143-145, 169-173) that can be used to develop tools and methods. In these cases, the tools can be brought to bear on more complex and real systems. Just as nanoscience began with the ability to image atoms and progressed to the ability to manipulate structures both directly and through guided interactions,(162, 163, 174-176) it has now become possible to control structure, materials, and chemical functionality from the submolecular to the centimeter scales simultaneously. Whereas substrates and surface functionalization have often been tailored to be resistant to bioadhesion, deliberate placement of chemical patterns can also be used for the growth and patterning of systems, such as biofilms, to be put into contact with nanoscale probes.(177-180) Such methods in combination with the tools of other fields (vide infra) will provide the means to probe and to understand microbiomes.

Key tools for the microbiome will need to be miniaturized and made parallel. These developments will leverage decades of work in nanotechnology in the areas of nanofabrication,(181) imaging systems,(182, 183) lab-on-a-chip systems,(184) control of biological interfaces,(185) and more. Commercialized and commoditized tools, such as smart phone cameras, can also be adapted for use (vide infra). By guiding the development and parallelization of these tools, increasingly complex microbiomes will be opened for study.(167)

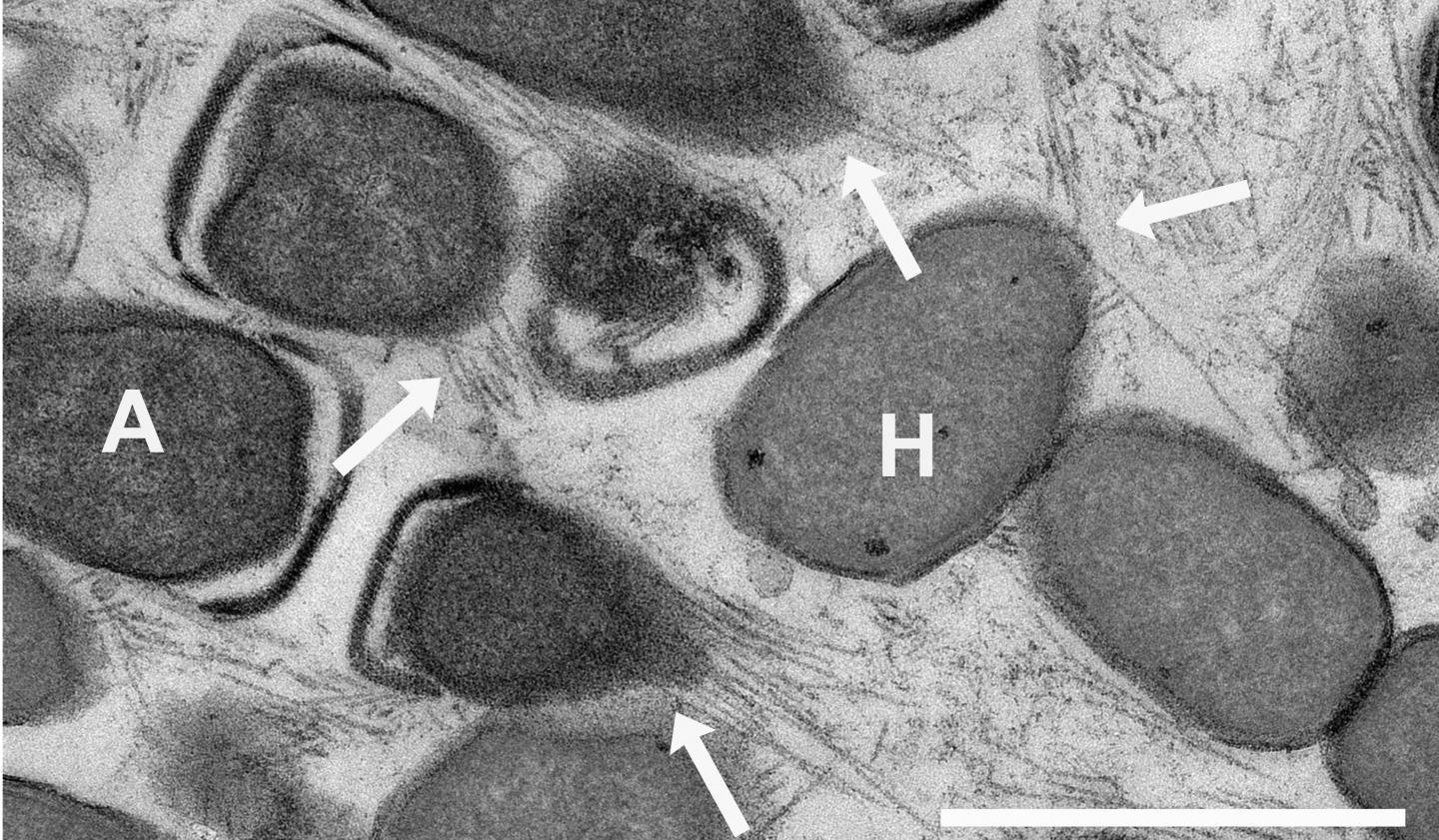

Imaging and sensing, in general, have been enjoying a Renaissance over the past decades, and there are various powerful measurement techniques that are currently available, making the Microbiome Initiative timely and exciting from the broad perspective of advanced analysis techniques. Recent advances in various -omics technologies, electron microscopy, optical microscopy/nanoscopy and spectroscopy, cytometry, mass spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy, nuclear imaging, and other techniques, create unique opportunities for researchers to investigate a wide range of questions related to microbiome interactions, function, and diversity. We anticipate that some of these advanced imaging, spectroscopy, and sensing techniques, coupled with big data analytics, will be used to create multimodal and integrated smart systems that can shed light onto some of the most important needs in microbiome research, including (1) analyzing microbial interactions specifically and sensitively at the relevant spatial and temporal scales; (2) determining and analyzing the diversity covered by the microbial genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome; (3) managing and manipulating microbiomes to probe their function, evaluating the impact of interventions and ultimately harnessing their activities; and (4) helping us identify and track microbial dark matter (referring to 99% of micro-organisms that cannot be cultured).

In this broad quest for creating next-generation imaging and sensing instrumentation to address the needs and challenges of microbiome-related research activities comprehensively, there are important issues that need to be considered, as discussed below.

The piece is extensive and quite interesting, if you have the time.