The University of California at Davis (UC Davis) and the University of Washington (state) collaborated in research into fundamental questions on how aquatic animals grow. From an Oct. 24, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

For the first time scientists can see how the shells of tiny marine organisms grow atom-by-atom, a new study reports. The advance provides new insights into the mechanisms of biomineralization and will improve our understanding of environmental change in Earth’s past.

An Oct. 24, 2016 UC Davis news release by Becky Oskin, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

Led by researchers from the University of California, Davis and the University of Washington, with key support from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the team examined an organic-mineral interface where the first calcium carbonate crystals start to appear in the shells of foraminifera, a type of plankton.

“We’ve gotten the first glimpse of the biological event horizon,” said Howard Spero, a study co-author and UC Davis geochemistry professor. …

Foraminifera’s Final Frontier

The researchers zoomed into shells at the atomic level to better understand how growth processes may influence the levels of trace impurities in shells. The team looked at a key stage — the interaction between the biological ‘template’ and the initiation of shell growth. The scientists produced an atom-scale map of the chemistry at this crucial interface in the foraminifera Orbulina universa. This is the first-ever measurement of the chemistry of a calcium carbonate biomineralization template, Spero said.

Among the new findings are elevated levels of sodium and magnesium in the organic layer. This is surprising because the two elements are not considered important architects in building shells, said lead study author Oscar Branson, a former postdoctoral researcher at UC Davis who is now at the Australian National University in Canberra. Also, the greater concentrations of magnesium and sodium in the organic template may need to be considered when investigating past climate with foraminifera shells.

Calibrating Earth’s Climate

Most of what we know about past climate (beyond ice core records) comes from chemical analyses of shells made by the tiny, one-celled creatures called foraminifera, or “forams.” When forams die, their shells sink and are preserved in seafloor mud. The chemistry preserved in ancient shells chronicles climate change on Earth, an archive that stretches back nearly 200 million years.

The calcium carbonate shells incorporate elements from seawater — such as calcium, magnesium and sodium — as the shells grow. The amount of trace impurities in a shell depends on both the surrounding environmental conditions and how the shells are made. For example, the more magnesium a shell has, the warmer the ocean was where that shell grew.

“Finding out how much magnesium there is in a shell can allow us to find out the temperature of seawater going back up to 150 million years,” Branson said.

But magnesium levels also vary within a shell, because of nanometer-scale growth bands. Each band is one day’s growth (similar to the seasonal variations in tree rings). Branson said considerable gaps persist in understanding what exactly causes the daily bands in the shells.

“We know that shell formation processes are important for shell chemistry, but we don’t know much about these processes or how they might have changed through time,” he said. “This adds considerable uncertainty to climate reconstructions.”

Atomic Maps

The researchers used two cutting-edge techniques: Time-of-Flight Secondary Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) and Laser-Assisted Atom Probe Tomography (APT). ToF-SIMS is a two-dimensional chemical mapping technique which shows the elemental composition of the surface of a polished sample. The technique was developed for the elemental analysis of complex polymer materials, and is just starting to be applied to natural samples like shells.

APT is an atomic-scale three-dimensional mapping technique, developed for looking at internal structures in advanced alloys, silicon chips and superconductors. The APT imaging was performed at the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

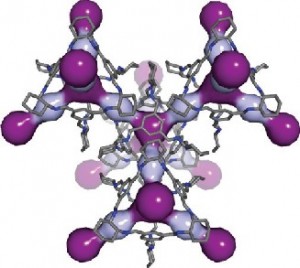

This foraminifera is just starting to form its adult spherical shell. The calcium carbonate spherical shell first forms on a thin organic template, shown here in white, around the dark juvenile skeleton. Calcium carbonate spines then extend from the juvenile skeleton through the new sphere and outward. The bright flecks are algae that the foraminifera “farm” for sustenance.Howard Spero/University of California, Davis

An Oct. 24, 2016 University of Washington (state) news release (also on EurekAlert) adds more information (there is a little repetition),

Unseen out in the ocean, countless single-celled organisms grow protective shells to keep them safe as they drift along, living off other tiny marine plants and animals. Taken together, the shells are so plentiful that when they sink they provide one of the best records for the history of ocean chemistry.

Oceanographers at the University of Washington and the University of California, Davis, have used modern tools to provide an atomic-scale look at how that shell first forms. Results could help answer fundamental questions about how these creatures grow under different ocean conditions, in the past and in the future. …

“There’s this debate among scientists about whether shelled organisms are slaves to the chemistry of the ocean, or whether they have the physiological capacity to adapt to changing environmental conditions,” said senior author Alex Gagnon, a UW assistant professor of oceanography.

The new work shows, he said, that they do exert some biologically-based control over shell formation.

“I think it’s just incredible that we were able to peer into the intricate details of those first moments that set how a seashell forms,” Gagnon said. “And that’s what sets how much of the rest of the skeleton will grow.”

The results could eventually help understand how organisms at the base of the marine food chain will respond to more acidic waters. And while the study looked at one organism, Orbulina universa, which is important for understanding past climate, the same method could be used for other plankton, corals and shellfish.

The study used tools developed for materials science and semiconductor research to view the shell formation in the most detail yet to see how the organisms turn seawater into solid mineral.

“We’re interested more broadly in the question ‘How do organisms make shells?'” said first author Oscar Branson, a former postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis who is now at Australian National University in Canberra. “We’ve focused on a key stage in mineral formation — the interaction between biological template materials and the initiation of shell growth by an organism.”

These tiny single-celled animals, called foraminifera, can’t reproduce anywhere but in their natural surroundings, which prevents breeding them in captivity. The researchers caught juvenile foraminifera by diving in deep water off Southern California. Then they then raised them in the lab, using tiny pipettes to feed them brine shrimp during their weeklong lives.

Marine shells are made from calcium carbonate, drawing the calcium and carbon from surrounding seawater. But the animal first grows a soft template for the mineral to grow over. Because this template is trapped within the growing skeleton, it acts as a snapshot of the chemical conditions during the first part of skeletal growth.

To see this chemical picture, the authors analyzed tiny sections of foraminifera template with a technique called atom probe tomography at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. This tool creates an atom-by-atom picture of the organic template, which was located using a chemical tag.

Results show that the template contains more magnesium and sodium atoms than expected, and that this could influence how the mineral in the shell begins to grow around it.

“One of the key stages in growing a skeleton is when you make that first bit, when you build that first bit of structure. Anything that changes that process is a key control point,” Gagnon said.

The clumping suggests that magnesium and sodium play a role in the first stages of shell growth. If their availability changes for any reason, that could influence how the shell grows beyond what simple chemistry would predict.

“We can say who the players are — further experiments will have to tell us exactly how important each of them is,” Gagnon said.

Follow-up work will try to grow the shells and create models of their formation to see how the template affects growth under different conditions, such as more acidic water.

“Translating that into, ‘Can these forams survive ocean acidification?’ is still many steps down the line,” Gagnon cautioned. “But you can’t do that until you have a picture of what that surface actually looks like.”

The researchers also hope that by better understanding the exact mechanism of shell growth they could tease apart different aspects of seafloor remains so the shells can be used to reconstruct more than just the ocean’s past temperature. In the study, they showed that the template was responsible for causing fine lines in the shells — one example of the rich chemical information encoded in fossil shells.

“There are ways that you could separate the effects of temperature from other things and learn much more about the past ocean,” Gagnon said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanometer-Scale Chemistry of a Calcite Biomineralization Template: Implications for Skeletal Composition and Nucleation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1522864113

This paper is behind a paywall.