I did not want to cash in (so to speak) on someone else’s fun headline so I played with it. Hre is the original head, which was likely written by either David Ruth or Mike Williams at Rice University (Texas, US), “Lettuce show you how to restore oil-soaked soil.”

A February 1, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily on the science behind lettuce and oil-soaked soil,

Rice University engineers have figured out how soil contaminated by heavy oil can not only be cleaned but made fertile again.

How do they know it works? They grew lettuce.

Rice engineers Kyriacos Zygourakis and Pedro Alvarez and their colleagues have fine-tuned their method to remove petroleum contaminants from soil through the age-old process of pyrolysis. The technique gently heats soil while keeping oxygen out, which avoids the damage usually done to fertile soil when burning hydrocarbons cause temperature spikes.

…

A February 1, 2019 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explains more about the work,

While large-volume marine spills get most of the attention, 98 percent of oil spills occur on land, Alvarez points out, with more than 25,000 spills a year reported to the Environmental Protection Agency. That makes the need for cost-effective remediation clear, he said.

“We saw an opportunity to convert a liability, contaminated soil, into a commodity, fertile soil,” Alvarez said.

The key to retaining fertility is to preserve the soil’s essential clays, Zygourakis said. “Clays retain water, and if you raise the temperature too high, you basically destroy them,” he said. “If you exceed 500 degrees Celsius (900 degrees Fahrenheit), dehydration is irreversible.

The researchers put soil samples from Hearne, Texas, contaminated in the lab with heavy crude, into a kiln to see what temperature best eliminated the most oil, and how long it took.

Their results showed heating samples in the rotating drum at 420 C (788 F) for 15 minutes eliminated 99.9 percent of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) and 94.5 percent of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), leaving the treated soils with roughly the same pollutant levels found in natural, uncontaminated soil.

The paper appears in the American Chemical Society journal Environmental Science and Technology. It follows several papers by the same group that detailed the mechanism by which pyrolysis removes contaminants and turns some of the unwanted hydrocarbons into char, while leaving behind soil almost as fertile as the original. “While heating soil to clean it isn’t a new process,” Zygourakis said, “we’ve proved we can do it quickly in a continuous reactor to remove TPH, and we’ve learned how to optimize the pyrolysis conditions to maximize contaminant removal while minimizing soil damage and loss of fertility.

“We also learned we can do it with less energy than other methods, and we have detoxified the soil so that we can safely put it back,” he said.

Heating the soil to about 420 C represents the sweet spot for treatment, Zygourakis said. Heating it to 470 C (878 F) did a marginally better job in removing contaminants, but used more energy and, more importantly, decreased the soil’s fertility to the degree that it could not be reused.

“Between 200 and 300 C (392-572 F), the light volatile compounds evaporate,” he said. “When you get to 350 to 400 C (662-752 F), you start breaking first the heteroatom bonds, and then carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds triggering a sequence of radical reactions that convert heavier hydrocarbons to stable, low-reactivity char.”

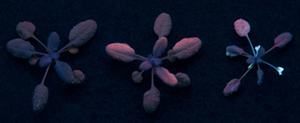

The true test of the pilot program came when the researchers grew Simpson black-seeded lettuce, a variety for which petroleum is highly toxic, on the original clean soil, some contaminated soil and several pyrolyzed soils. While plants in the treated soils were a bit slower to start, they found that after 21 days, plants grown in pyrolyzed soil with fertilizer or simply water showed the same germination rates and had the same weight as those grown in clean soil.

“We knew we had a process that effectively cleans up oil-contaminated soil and restores its fertility,” Zygourakis said. “But, had we truly detoxified the soil?”

To answer this final question, the Rice team turned to Bhagavatula Moorthy, a professor of neonatology at Baylor College of Medicine, who studies the effects of airborne contaminants on neonatal development. Moorthy and his lab found that extracts taken from oil-contaminated soils were toxic to human lung cells, while exposing the same cell lines to extracts from treated soils had no adverse effects. The study eased concerns that pyrolyzed soil could release airborne dust particles laced with highly toxic pollutants like PAHs.

”One important lesson we learned is that different treatment objectives for regulatory compliance, detoxification and soil-fertility restoration need not be mutually exclusive and can be simultaneously achieved,” Alvarez said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Pilot-Scale Pyrolytic Remediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Soil in a Continuously-Fed Reactor: Treatment Intensity Trade-Offs by Wen Song, Julia E. Vidonish, Roopa Kamath, Pingfeng Yu, Chun Chu, Bhagavatula Moorthy, Baoyu Gao, Kyriacos Zygourakis, and Pedro J. J. Alvarez. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2019, 53 (4), pp 2045–2053 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b05825 Publication Date (Web): January 25, 2019

Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.