This work on quantum networks comes from a joint Singapore/UK research project, from a June 2, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

You can’t sign up for the quantum internet just yet, but researchers have reported a major experimental milestone towards building a global quantum network — and it’s happening in space.

With a network that carries information in the quantum properties of single particles, you can create secure keys for secret messaging and potentially connect powerful quantum computers in the future. But scientists think you will need equipment in space to get global reach.

Researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the University of Strathclyde, UK, have become the first to test in orbit technology for satellite-based quantum network nodes.

They have put a compact device carrying components used in quantum communication and computing into orbit. And it works: the team report first data in a paper published 31 May 2016 in the journal Physical Review Applied.

A June 2, 2016 National University of Singapore press release, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

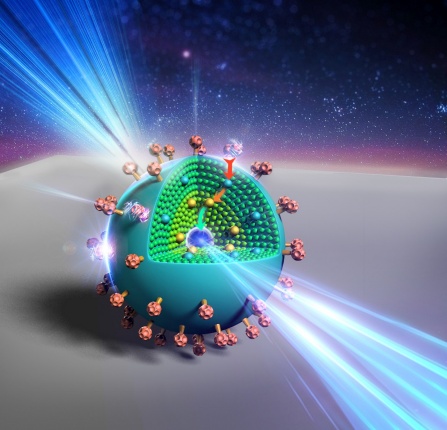

The team’s device, dubbed SPEQS, creates and measures pairs of light particles, called photons. Results from space show that SPEQS is making pairs of photons with correlated properties – an indicator of performance.

Team-leader Alexander Ling, an Assistant Professor at the Centre for Quantum Technologies (CQT) at NUS said, “This is the first time anyone has tested this kind of quantum technology in space.”

The team had to be inventive to redesign a delicate, table-top quantum setup to be small and robust enough to fly inside a nanosatellite only the size of a shoebox. The whole satellite weighs just 1.65-kilogramme.

Towards entanglement

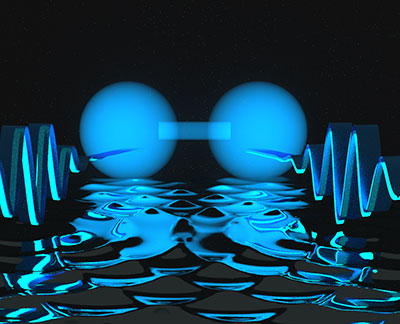

Making correlated photons is a precursor to creating entangled photons. Described by Einstein as “spooky action at a distance”, entanglement is a connection between quantum particles that lends security to communication and power to computing.

Professor Artur Ekert, Director of CQT, invented the idea of using entangled particles for cryptography. He said, “Alex and his team are taking entanglement, literally, to a new level. Their experiments will pave the road to secure quantum communication and distributed quantum computation on a global scale. I am happy to see that Singapore is one of the world leaders in this area.”

Local quantum networks already exist [emphasis mine]. The problem Ling’s team aims to solve is a distance limit. Losses limit quantum signals sent through air at ground level or optical fibre to a few hundred kilometers – but we might ultimately use entangled photons beamed from satellites to connect points on opposite sides of the planet. Although photons from satellites still have to travel through the atmosphere, going top-to-bottom is roughly equivalent to going only 10 kilometres at ground level.

The group’s first device is a technology pathfinder. It takes photons from a BluRay laser and splits them into two, then measures the pair’s properties, all on board the satellite. To do this it contains a laser diode, crystals, mirrors and photon detectors carefully aligned inside an aluminum block. This sits on top of a 10 centimetres by 10 centimetres printed circuit board packed with control electronics.

Through a series of pre-launch tests – and one unfortunate incident – the team became more confident that their design could survive a rocket launch and space conditions. The team had a device in the October 2014 Orbital-3 rocket which exploded on the launch pad. The satellite containing that first device was later found on a beach intact and still in working order.

Future plans

Even with the success of the more recent mission, a global network is still a few milestones away. The team’s roadmap calls for a series of launches, with the next space-bound SPEQS slated to produce entangled photons. SPEQS stands for Small Photon-Entangling Quantum System.

With later satellites, the researchers will try sending entangled photons to Earth and to other satellites. The team are working with standard “CubeSat” nanosatellites, which can get relatively cheap rides into space as rocket ballast. Ultimately, completing a global network would mean having a fleet of satellites in orbit and an array of ground stations.

In the meantime, quantum satellites could also carry out fundamental experiments – for example, testing entanglement over distances bigger than Earth-bound scientists can manage. “We are reaching the limits of how precisely we can test quantum theory on Earth,” said co-author Dr Daniel Oi at the University of Strathclyde.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Generation and Analysis of Correlated Pairs of Photons aboard a Nanosatellite by Zhongkan Tang, Rakhitha Chandrasekara, Yue Chuan Tan, Cliff Cheng, Luo Sha, Goh Cher Hiang, Daniel K. L. Oi, and Alexander Ling. Phys. Rev. Applied 5, 054022 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.5.054022 Published 31 May 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.