This is the first time I’ve seen an item about tissue engineering which concerns plant life. An August 27, 2015 news item on Azonano describes the latest development with plant cells,

Miniscule artificial scaffolding units made from nano-fibre polymers and built to house plant cells have enabled scientists to see for the first time how individual plant cells behave and interact with each other in a three-dimensional environment.

These “hotels for cells” mimic the ‘extracellular matrix’ which cells secrete before they grow and divide to create plant tissue. [Note: Human and other cells also have extracellular matrices] This environment allows scientists to observe and image individual plant cells developing in a more natural, multi-dimensional environment than previous ‘flat’ cell cultures.

An August 26, 2015 University of Cambridge press release, which originated the news item, describes the research and mentions the pioneering technologies which made it possible,

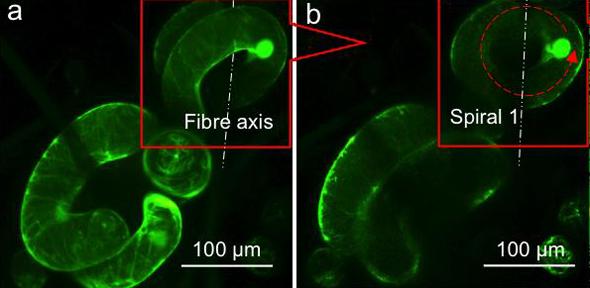

The research team were surprised to see individual plant cells clinging to and winding around their fibrous supports; reaching past neighbouring cells to wrap themselves to the artificial scaffolding in a manner reminiscent of vines growing.

Pioneering new in vitro techniques combining recent developments in 3-D scaffold development and imaging, scientists say they observed plants cells taking on growth and structure of far greater complexity than has ever been seen of plant cells before, either in living tissue or cell culture.

“Previously, plant cells in culture had only been seen in round or oblong forms. Now, we have seen 3D cultured cells twisting and weaving around their new supports in truly remarkable ways, creating shapes we never thought possible and never seen before in any plant,” said plant scientist and co-author Raymond Wightman.

“We can use this tool to explore how a whole plant is formed and at the same time to create new materials.”

This ability for single plant cells to attach themselves by growing and spiralling around the scaffolding suggests that cells of land plants have retained the ability of their evolutionary ancestors – aquatic single-celled organisms, such as Charophyta algae – to stick themselves to inert structures.

While similar ‘nano-scaffold’ technology has long been used for mammalian cells, resulting in the advancement of tissue engineering research, this is the first time such technology has been used for plant cells – allowing scientists to glimpse in 3-D the individual cell interactions that lead to the forming of plant tissue.

The scientists say the research “defines a new suite of techniques” for exploring cell-environment interactions, allowing greater understating of fundamental plant biology that could lead to new types of biomaterials and help provide solutions to sustainable biomass growth.

…

“While we can peer deep inside single cells and understand their functions, when researchers study a ‘whole’ plant, as in fully formed tissue, it is too difficult to disentangle the many complex interactions between the cells, their neighbours, and their behaviour,” said Wightman.

“Until now, nobody had tried to put plant cells in an artificial fibre scaffold that replicates their natural environment and tried to observe their interactions with one or two other cells, or fibre itself,” he said.

Co-author and material scientist Dr Stoyan Smoukov suggests that a possible reason why artificial scaffolding on plant cells had never been done before was the expense of 3D nano-fibre matrices (the high costs have previously been justified in mammalian cell research due to its human medical potential).

However, Smoukov has co-discovered and recently helped commercialise a new method for producing polymer fibres for 3-D scaffolds inexpensively and in bulk. ‘Shear-spinning’ produces masses of fibre, in a technique similar to creating candy-floss in nano-scale. The researchers were able to adapt such scaffolds for use with plant cells.

This approach was combined with electron microscopy imaging technology. In fact, using time-lapse photography, the researchers have even managed to capture 4-D footage of these previously unseen cellular structures. “Such high-resolution moving images allowed us to follow internal processes in the cells as they develop into tissues,” said Smoukov, who is already working on using the methods in this plant study to research mammalian cancer cells.

Here’s an image illustrating the research,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A 3-dimensional fibre scaffold as an investigative tool for studying the morphogenesis of isolated plant pells [cells?] by CJ Luo, Raymond Wightman, Elliot Meyerowitz, and Stoyan K. Smoukov. BMC Plant Biology 2015, 15:211 doi:10.1186/s12870-015-0581-7

This paper is open access.