A February 24, 2022 news item on phys.org describes research into using proteins as electrical conductors,

Proteins are among the most versatile and ubiquitous biomolecules on earth. Nature uses them for everything from building tissues to regulating metabolism to defending the body against disease.

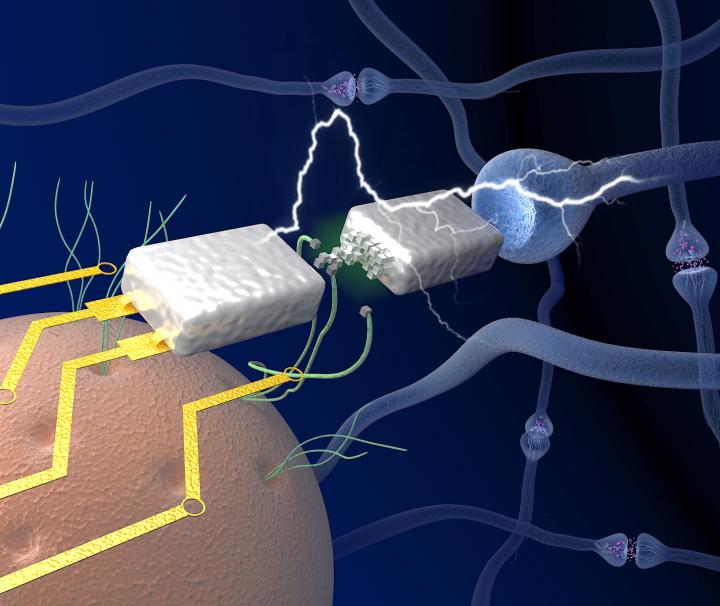

Now, a new study shows that proteins have other, largely unexplored capabilities. Under the right conditions, they can act as tiny, current-carrying wires, useful for a range human-designed nanoelectronics.

….

A February 25, 2022 Arizona State University (ASU) news release (also on EurekAlert but published February 24, 2022), which originated the news item, delves further into the intricacies of nanoelectronics (Note: Links have been removed),

In new research appearing in the journal ACS Nano, Stuart Lindsay and his colleagues show that certain proteins can act as efficient electrical conductors. In fact, these tiny protein wires may have better conductance properties than similar nanowires composed of DNA [deoxyribonucleic acid], which have already met with considerable success for a host of human applications.

Professor Lindsay directs the Biodesign Center for Single-Molecule Biophysics. He is also professor with ASU’s Department of Physics and the School of Molecular Sciences.

Just as in the case of DNA, proteins offer many attractive properties for nanoscale electronics including stability, tunable conductance and vast information storage capacity. Although proteins had traditionally been regarded as poor conductors of electricity, all that recently changed when Lindsay and his colleagues demonstrated that a protein poised between a pair of electrodes could act as an efficient conductor of electrons.

The new research examines the phenomenon of electron transport through proteins in greater detail. The study results establish that over long distances, protein nanowires display better conductance properties than chemically-synthesized nanowires specifically designed to be conductors. In addition, proteins are self-organizing and allow for atomic-scale control of their constituent parts.

Synthetically designed protein nanowires could give rise to new ultra-tiny electronics, with potential applications for medical sensing and diagnostics, nanorobots to carry out search and destroy missions against diseases or in a new breed of ultra-tiny computer transistors. Lindsay is particularly interested in the potential of protein nanowires for use in new devices to carry out ultra-fast DNA and protein sequencing, an area in which he has already made significant strides.

In addition to their role in nanoelectronic devices, charge transport reactions are crucial in living systems for processes including respiration, metabolism and photosynthesis. Hence, research into transport properties through designed proteins may shed new light on how such processes operate within living organisms.

While proteins have many of the benefits of DNA for nanoelectronics in terms of electrical conductance and self-assembly, the expanded alphabet of 20 amino acids used to construct them offers an enhanced toolkit for nanoarchitects like Lindsay, when compared with just four nucleotides making up DNA.

Transit Authority

Though electron transport has been a focus of considerable research, the nature of the flow of electrons through proteins has remained something of a mystery. Broadly speaking, the process can occur through electron tunneling, a quantum effect occurring over very short distances or through the hopping of electrons along a peptide chain—in the case of proteins, a chain of amino acids.

One objective of the study was to determine which of these regimes seemed to be operating by making quantitative measurements of electrical conductance over different lengths of protein nanowire. The study also describes a mathematical model that can be used to calculate the molecular-electronic properties of proteins.

For the experiments, the researchers used protein segments in four nanometer increments, ranging from 4-20 nanometers in length. A gene was designed to produce these amino acid sequences from a DNA template, with the protein lengths then bonded together into longer molecules. A highly sensitive instrument known as a scanning tunneling microscope was used to make precise measurements of conductance as electron transport progressed through the protein nanowire.

The data show that conductance decreases over nanowire length in a manner consistent with hopping rather than tunneling behavior of the electrons. Specific aromatic amino acid residues, (six tyrosines and one tryptophan in each corkscrew twist of the protein), help guide the electrons along their path from point to point like successive stations along a train route. “The electron transport is sort of like skipping stone across water—the stone hasn’t got time to sink on each skip,” Lindsay says.

Wire wonders

While the conductance values of the protein nanowires decreased over distance, they did so more gradually than with conventional molecular wires specifically designed to be efficient conductors.

When the protein nanowires exceeded six nanometers in length, their conductance outperformed molecular nanowires, opening the door to their use in many new applications. The fact that they can be subtly designed and altered with atomic scale control and self-assembled from a gene template permits fine-tuned manipulations that far exceed what can currently be achieved with conventional transistor design.

One exciting possibility is using such protein nanowires to connect other components in a new suite of nanomachines. For example, nanowires could be used to connect an enzyme known as a DNA polymerase to electrodes, resulting in a device that could potentially sequence an entire human genome at low cost in under an hour. A similar approach could allow the integration of proteosomes into nanoelectronic devices able to read amino acids for protein sequencing.

“We are beginning now to understand the electron transport in these proteins. Once you have quantitative calculations, not only do you have great molecular electronic components, but you have a recipe for designing them,” Lindsay says. “If you think of the SPICE program that electrical engineers use to design circuits, there’s a glimmer now that you could get this for protein electronics.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Electronic Transport in Molecular Wires of Precisely Controlled Length Built from Modular Proteins by Bintian Zhang, Eathen Ryan, Xu Wang, Weisi Song, and Stuart Lindsay. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 1, 1671–1680 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c10830 Publication Date:January 14, 2022 Copyright © 2022 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.