A team of researchers at the University of Toronto (Canada) have developed a technique for the therapeutic use of proteins that doesn’t require ‘nanoencapsulation’ although nanoparticles are still used according to a May 27, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

A U of T [University of Toronto] Engineering team has designed a simpler way to keep therapeutic proteins where they are needed for long periods of time. The discovery is a potential game-changer for the treatment of chronic illnesses or injuries that often require multiple injections or daily pills.

For decades, biomedical engineers have been painstakingly encapsulating proteins in nanoparticles to control their release. Now, a research team led by University Professor Molly Shoichet has shown that proteins can be released over several weeks, even months, without ever being encapsulated. In this case the team looked specifically at therapeutic proteins relevant to tissue regeneration after stroke and spinal cord injury.

“It was such a surprising and unexpected discovery,” said co-lead author Dr. Irja Elliott Donaghue, who first found that the therapeutic protein NT3, a factor that promotes the growth of nerve cells, was slowly released when just mixed into a Jello-like substance that also contained nanoparticles. “Our first thought was, ‘What could be happening to cause this?'”

A May 27, 2016 University of Toronto news release (also on EurekAlert) by Marit Mitchell, which originated the news item, provides more in depth explanation,

Proteins hold enormous promise to treat chronic conditions and irreversible injuries — for example, human growth hormone is encapsulated in these tiny polymeric particles, and used to treat children with stunted growth. In order to avoid repeated injections or daily pills, researchers use complicated strategies both to deliver proteins to their site of action, and to ensure they’re released over a long enough period of time to have a beneficial effect.

This has long been a major challenge for protein-based therapies, especially because proteins are large and often fragile molecules. Until now, investigators have been treating proteins the same way as small drug molecules and encapsulating them in polymeric nanoparticles, often made of a material called poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) or PLGA.

As the nanoparticles break down, the drug molecules escape. The same process is true for proteins; however, the encapsulating process itself often damages or denatures some of the encapsulated proteins, rendering them useless for treatment. Skipping encapsulation altogether means fewer denatured proteins, making for more consistent protein therapeutics that are easier to make and store.

“This is really exciting from a translational perspective,” said PhD candidate Jaclyn Obermeyer. “Having a simpler, more reliable fabrication process leaves less room for complications with scale-up for clinical use.”

The three lead authors, Elliott Donoghue, Obermeyer and Dr. Malgosia Pakulska have shown that to get the desired controlled release, proteins only need to be alongside the PLGA nanoparticles, not inside them. …

“We think that this could speed up the path for protein-based drugs to get to the clinic,” said Elliott Donaghue.

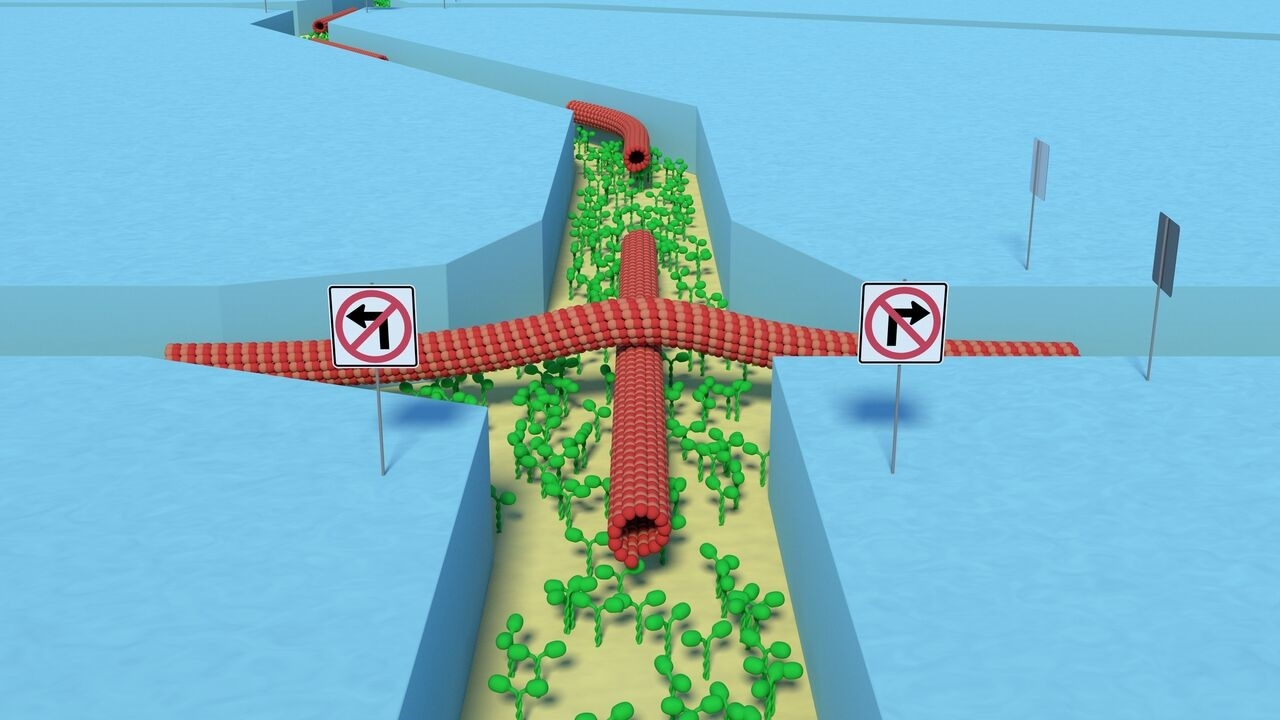

The mechanism for this encapsulation-free controlled release is surprisingly elegant. Shoichet’s group mixes the proteins and nanoparticles in a Jello-like substance called a hydrogel, which keeps them localized when injected at the site of injury. The positively charged proteins and negatively charged nanoparticles naturally stick together. As the nanoparticles break down they make the solution more acidic, weakening the attraction and letting the proteins break free.

“We are particularly excited to show long-term, controlled protein release by simply controlling the electrostatic interactions between proteins and polymeric nanobeads,” said Shoichet. “By manipulating the pH of the solution, the size and number of nanoparticles, we can control release of bioactive proteins. This has already changed and simplified the protein release strategies that we are pursuing in pre-clinical models of disease in the brain and spinal cord.”

“We’ve learned how to control this simple phenomena,” Pakulska said. “Our next question is whether we can do the opposite—design a similar release system for positively charged nanoparticles and negatively charged proteins.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Encapsulation-free controlled release: Electrostatic adsorption eliminates the need for protein encapsulation in PLGA nanoparticles by Malgosia M. Pakulska, Irja Elliott Donaghue, Jaclyn M. Obermeyer, Anup Tuladhar, Christopher K. McLaughlin, Tyler N. Shendruk, and Molly S. Shoichet. Science Advances 27 May 2016: Vol. 2, no. 5, e1600519 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1600519

This paper appears to be open access.

Dr. Molly Shoichet was featured here in a May 11, 2015 posting about the launch of her Canada-wide science communication project Research2.Reality.