I’ve been to two new exhibitions in Vancouver (Canada) and while both could be described as mashups, only one uses the word in its title. Before getting to the shows, here’s a little bit about mashups for anyone who’s not familiar with word.

A mashup definition

Generally speaking a mashup is when you bring together multiple source materials to create something new. Here’s a list of different types of mashups, from the Mashup Wikipedia entry,

Mashup may refer to:

- Mashup (music), the musical genre encompassing songs which consist entirely of parts of other songs

- Mashup (video), a video that is edited from more than one source to appear as one

- Mashup (book), a book which combines a pre-existing text, often a classic work of fiction, with a certain popular genre such as vampire or zombie narratives

- Mashup (web application hybrid), a web application that combines data and/or functionality from more than one source

- Mash-Up (Glee), a musical theater performance composed of integrated segments from other performances as popularized by the American television series Glee

- Mash Up (TV series), a television show on Comedy Central starring T.J. Miller.

- Lotus Mashups, a Business Mashups editor developed and distributed by IBM as part of the IBM Mashup Center system

- Band Mashups, the former name of the video game Battle of the Bands

While the book mashup seems relatively new, there have been other older literary mashups such as cut-up technique (Note: Links have been removed),

The cut-up technique (or découpé in French) is an aleatory literary technique in which a text is cut up and rearranged to create a new text. The concept can be traced to at least the Dadaists of the 1920s, but was popularized in the late 1950s and early 1960s by writer William S. Burroughs, and has since been used in a wide variety of contexts.

Arguably although problematically, the exquisite corpse could be included as a literary mashup (Note: Links have been removed),

Exquisite corpse, also known as exquisite cadaver (from the original French term cadavre exquis) or rotating corpse, is a method by which a collection of words or images is collectively assembled. Each collaborator adds to a composition in sequence, either by following a rule (e.g. “The adjective noun adverb verb the adjective noun”, as in “The green duck sweetly sang the dreadful dirge”) or by being allowed to see only the end of what the previous person contributed.

The technique was invented by surrealists and is similar to an old parlour game called Consequences in which players write in turn on a sheet of paper, fold it to conceal part of the writing, and then pass it to the next player for a further contribution. Surrealism principal founder André Breton reported that it started in fun, but became playful and eventually enriching. Breton said the diversion started about 1925, but Pierre Reverdy wrote that it started much earlier, at least before 1918.

In any event, music mashups (also called remix amongst other things) seem to have predated any other mashups, from the Mashup (music) Wikipedia entry,

A mashup (also mesh, mash up, mash-up, blend, bootleg[1] and bastard pop/rock) is a song or composition created by blending two or more pre-recorded songs, usually by overlaying the vocal track of one song seamlessly over the instrumental track of another.[2] …

…

The practice of assembling new songs from purloined elements of other tracks stretches back to the beginnings of recorded music [emphasis mine]. If one extends the definition beyond the realm of pop, precursors can be found in musique concrète, as well as the classical practice of (re-)arranging traditional folk material and the jazz tradition of reinterpreting standards. In addition, many elements of mashup culture have antecedents in hip hop and the DIY ethic of punk as well as overlap with the free culture movement.

Recorded music seems to have started sometime in the 1870’s, from the History of Sound Recording Wikipedia entry,

The history of sound recording – which has progressed in waves, driven by the invention and commercial introduction of new technologies – can be roughly divided into four main periods:

- the “Acoustic” era, 1877 to 1925

- the “Electrical” era, 1925 to 1945 (including sound on film)

- the “Magnetic” era, 1945 to 1975

- the “Digital” Era, 1975 to the present day.

It seems the musicians got there first. That settled, it’s time for the visual art exhibition that’s a mashup in principle if not in name. (Although Robin Laurence in part 2 makes a compelling case for the 18th century visual artist, Mary Delany and her ‘paper-mosaiks’ (scroll down about 75% of the way; it’s in the subsection titled ‘Reviews and commentaries from elsewhere’).

Rennie Collection

While he’s made his money as a Vancouver real estate marketer, Bob Rennie is better known internationally as someone who is passionately committed to the visual arts. Crowned as one of the top 200 art collectors in the world by ArtNews, Rennie rated both a profile in ArtNews and a mention in the ArtNet News April 30, 2015 article, Top 200 Art Collectors Worldwide for 2015, Part Two. According to his entry on Wikipedia, there’s also this (Note: Links have been removed),

Rennie chairs the North America Acquisitions Committee (NAAC) at Tate Museum in London,[5]is a member of the Tate International Council and sits on the Dean’s Advisory Board to the Faculty of Arts at the University of British Columbia (since 2006). In recognition of his dedication to the arts and the arts community, he received an honorary doctorate of letters from Emily Carr University of Art and Design in 2008, and was appointed to the university’s Board of Governors in 2009.

Rennie joined the Board of Trustees at The Art Institute of Chicago in 2015.[6]

The current exhibition at the Rennie Collection (where pieces from his extensive art collection are displayed) is untitled and unique. The show was curated by Rennie himself (from the Rennie Collection Jan. ??, 2016 news release),

Rennie Collection is proud to present a major group exhibition featuring 41 prominent and emerging artists. Bringing together a variety of practices and media, this survey aims to reveal the chaos of the world by addressing enduringly pertinent issues, from migratory displacement to an in-depth examination of identity and history. The exhibition runs from January 23 to April 23, 2016 [ETA April 4, 2016: The show has been extended to Friday, May 20, 2016.].

…

“This is our twelfth exhibition at the Rennie Museum, with works from the collection. Although we never burden our shows with a formal title, the working title for this install− which mines 41 artists from the collection − is ‘chaos’. Given the chaos of the world, I wanted to bring tough topics into conversations.

From the first work that ever entered the collection, Norman Rockwells On Top of The World (1933) – a utopian world that I thought actually existed outside my childhood home in Vancouver’s eastside – through to Bob Beck’s Thirteen Shooters (2001) showcasing the Columbine killers – the world stopped sixteen years ago hearing the news of a school massacre – my concern today, and a focus of the exhibition, is on elevating the topics in the show. We just don’t stop anymore upon hearing the news.

…

For anyone familiar with the Rennie Collection, it is in a heritage building in one of the oldest parts of Vancouver. The building houses both the ‘gallery’ and Rennie’s real estate marketing business. Visits (tours) to see an exhibition must be booked; there is no ‘dropping in’.

When I attended, over 15 of us were booked for a visit, we were introduced to the exhibit by Whitney (a student from the University of British Columbia art history programme). Usually you get an introduction to every single piece in the exhibit but with over 41 artists represented and, I believe, 53 pieces being shown that proved to be impossible. That said, there is one piece which is likely to be everyone’s starting part and that is the camel or more precisely, John Baldessari’s 2013 Camel (Albino) Contemplating Needle (Large) on the ground floor by picture window where passersby can look in from the street.

The piece looks like a giant lump of camel-shaped plastic, smooth and white. The artist has coloured in the eyes which from most angles seem to be gazing not at the needle before it but heavenward. It is as you’ve likely guessed a reference to the saying about rich men having as much chance of getting into heaven as a camel has of passing through the eye of a needle. Whitney informed us that the saying can, more or less, be associated with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. (If you look on Wikipedia (Eye of a needle) entry, you’ll find it can also be associated with the Bahá’í faith.) By the way, the saying is written on the gallery wall in Arabic.

It seems telling that the first piece is about rich men and their difficulty getting to heaven in a show curated by a rich man (Rennie’s stated intention seen later in this post does not resemble my response to the piece). Then, further into the gallery’s first floor, there are pieces by Jota Castro titled ‘Motherfuckers never die’. One of the pieces features a list of art collectors, both individual and corporate (not including Rennie), with the title prominently featured as the headline. It suggests a highly self-critical view both personally and socially, which is borne out through the rest of the exhibition.

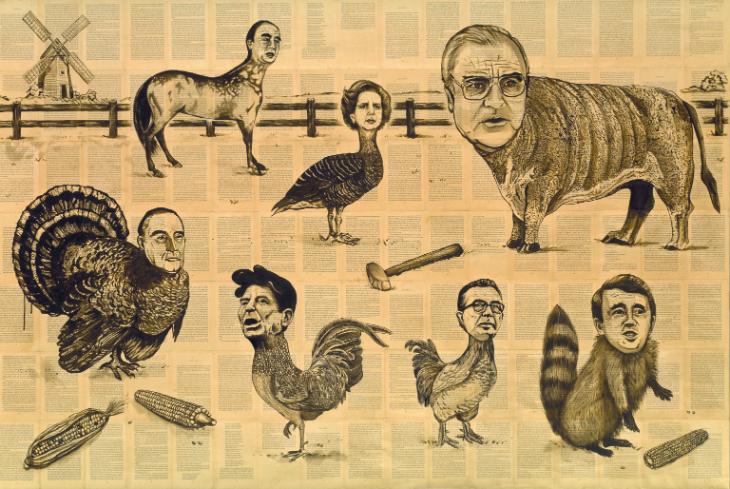

Upstairs, the second floor is an overwhelming experience given that its three galleries are loaded with the bulk of the items. One of the more engaging pieces for me was ‘Animal Farm ’92 (after George Orwell)’, 1992 by Tim Rollins and K.O.S.

Orwell’s book ‘Animal Farm’ has been ripped apart so the pages could be glued to a huge canvas or some other surface. Over top of the book’s pages, artists have rendered political figures of the period as animals. The usual suspects are present: the US president, China’s president, France’s president, Japan’s prime minister and, more excitingly, leaders who are largely unknown outside their own countries. It was fascinatingly comprehensive.

The Tate (UK art gallery) has an image which shows you what I’m trying to describe but in no way conveys the scale,

Animal Farm – G7 1989-92 Tim Rollins born 1955 Lent from a private collection 2000 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/L02312

You could spend hours contemplating the geopolitical and social implications both then and now. As well, the piece has an interesting story of its own as can be seen on the Tim Rollins and K.O.S webpage on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Press website,

In August 1981, artist and activist Tim Rollins was recruited by the principal of Intermediate School 52 in the South Bronx to develop a curriculum that combined art-making with lessons in reading and writing for students classified as “at risk.” On the first day of school, Rollins told his students, “Today we are going to make art, but we are also going to make history.” This book unfolds that history, offering the first comprehensive catalog of work created collaboratively by Rollins and several generations of students, now known as the “Kids of Survival.”

Rollins and his students developed a way of working that combined art-making with reading literature and writing personal narratives: Rollins or a student would read aloud from classic literary texts by such authors as Shakespeare and Orwell while the rest of the class drew or wrote on the pages being read, connecting the stories to their own experiences. Often, Rollins and his students (who later named themselves “Kids of Survival” or K.O.S.) cut out book pages and laid them on a grid on canvas before undertaking their graphic interventions. This process developed into the group’s signature style, which they applied to literary texts, musical scores, and other printed matter. This book and the accompanying major museum retrospective document the history of the groundbreaking practice of Tim Rollins and K.O.S., with full color images of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and prints. These include a caricature of Jesse Helms with an animal body drawn on the pages of Animal Farm; graffiti-like images painted in acrylic on the pages of Frankenstein; a gleaming pattern of fantastical golden horns on Kafka’s Amerika; and a series of red letter A’s on The Scarlet Letter.

As promised, social issues dominate this Rennie Collection show throughout. Ai Wei Wei’s ‘Coloured Vases’ (2009) with industrial paint covering and cheapening seven Han era dynasty vases, Brian Jungen’s mishapened and blackened Ku Klux Hood (‘Untitled’, 2015), and Judy Chartrand’s ‘If this is what you call “Being Civilized” I’d rather go back to “Being Savage …”‘ hotel bowls (2003) which ahs drawings of cockroaches included with the decorative imagery, call viewers to take into account their own biases. Wei Wei’s vases are cheap and garish, it’s on learning that Han era vases are beneath the paint that the viewer is forced to reevaluate the piece and his or her own judgment. Chartrand’s cockroaches blend in with the decor and it takes a minute or two to recognize them for what they are and recoil. The experience is a bit shocking and for locals who recognize the names of the three hotel bowls represented, the link to the Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is searing. Jungen’s second piece (Untitled) in this show is on the floor, the shape not readily seen, and the colour black. Once Whitney told us it was meant to represent a Ku Klux Klan hood, we were presented with a problem. When something as iconic as a white, cloth, KKK hood is represented by a misshapen lump of solid black plastic and is on the floor unrecognizable as a hood, one has to resolve cognitive dissonance.

The show ends on the third floor where the Norman Rockwell print ‘On Top of the World’ (1933) mentioned in the news release is bracketed by two pieces by Anton Kannemeyer ‘W is for White’ (2007) on the left (once also known as the ‘sinister’ side) & ‘B is for Black’ (2007) on the right. Rennie’s first art purchase representing an idealized world he (and many others) have aspired to is bracketed by Kannemeyer’s pieces, which feature definitions for white and black found in the Oxford English Dictionary and are illustrated with crude racist images. The effect is of one more disturbance added to a series experienced in this show. One final discombobulating experience (I’m not sure if it’s intentional *ETA March 8, 2016 1720 hours: Yes, it is according to Wendy Chang of the Rennie Collection*) is due to a permanent installation seen from the rooftop, Martin Creed’s strangely reassuring neon words ‘EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT’. All you have to do is go to the door which opens onto the roof and turn your head to the left and you can either view the Creed piece through the glass door or step out onto the roof.

If there’s any doubt that Rennie intends to disconcert and disturb the viewer, a January ??, 2016 Rennie Collection news release clarifies the matter,

…

Social commentary and artist’s approach to reporting the news has always interested me – Gilbert and George’s Bomb from 2006, or the questioning of commerce in the backroom photos of Amazon by Hugh Scott-Douglas, John Baldessari’s albino camel bringing ancient proverbs into question [my response was not that as noted earlier], and Glenn Ligon’s ‘fallen America’. I felt it was time to stop looking at the world’s chaos in isolation and let you see into the world in accumulation. If you leave sad, tense or somewhat suffocated, then I have… you know, I don’t know really what I have done, other than reminded us that when one of us has a problem, we all have a problem. [emphasis mine]

Thank you so much for questioning the world with me…”

Bob Rennie

Here’s an image of Rennie with the Martin Creed piece visible behind him,

Finally, Rennie’s comment that one of us having a problem means we all do brought to mind this,Part 2 covers the mashup at the Vancouver Art Gallery and more.

![[downloaded from http://www.artnews.com/top200/bob-rennie/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/BobRennie.jpg)