According to an April 27, 2016 news item on Nanowerk researchers at the University of Toronto (Canada) along with their collaborators in the US (Harvard Medical School) and Japan (University of Tokyo) have determined that less than 1% of nanoparticle-based drugs reach their intended destination (Note: A link has been removed),

Targeting cancer cells for destruction while leaving healthy cells alone — that has been the promise of the emerging field of cancer nanomedicine. But a new meta-analysis from U of T’s [University of Toronto] Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering (IBBME) indicates that progress so far has been limited and new strategies are needed if the promise is to become reality.

“The amount of research into using engineered nanoparticles to deliver cancer drugs directly to tumours has been growing steadily over the last decade, but there are very few formulations used in patients. The question is why?” says Professor Warren Chan (IBBME, ChemE, MSE), senior author on the review paper published in Nature Reviews Materials (“Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours”). “We felt it was time to look at the field more closely.”

An April 25, 2016 U of T news release, which originated the news item, details the research,

Chan and his co-authors analysed 117 published papers that recorded the delivery efficiency of various nanoparticles to tumours — that is, the percentage of injected nanoparticles that actually reach their intended target. To their surprise, they found that the median value was about 0.7 per cent of injected nanoparticles reaching their targets, and that this number has not changed for the last ten years. “If the nanoparticles do not get delivered to the tumour, they cannot work as designed for many nanomedicines,” says Chan.

Even more surprising was that altering nanoparticles themselves made little difference in the net delivery efficiency. “Researchers have tried different materials and nanoparticle sizes, different surface coatings, different shapes, but all these variations lead to no difference, or only small differences,” says Stefan Wilhelm, a post-doctoral researcher in Chan’s lab and lead author of the paper. “These results suggest that we have to think more about the biology and the mechanisms that are involved in the delivery process rather than just changing characteristics of nanoparticles themselves.”

Wilhelm points out that nanoparticles do have some advantages. Unlike chemotherapy drugs which go everywhere in the body, drugs delivered by nanoparticles accumulate more in some organs and less in others. This can be beneficial: for example, one current treatment uses nanoparticles called liposomes to encapsulate the cancer drug doxorubicin.

This encapsulation reduces the accumulation of doxorubicin in the heart, thereby reducing cardiotoxicity compared with administering the drug on its own.

Unfortunately, the majority of injected nanoparticles, including liposomes, end up in the liver, spleen and kidneys, which is logical since the job of these organs is to clear foreign substances and poisons from the blood. This suggests that in order to prevent nanoparticles from being filtered out of the blood before they reach the target tumour, researchers may have to control the interactions of those organs with nanoparticles.

It may be that there is an optimal particle surface chemistry, size, or shape required to access each type of organ or tissue. One strategy the authors are pursuing involves engineering nanoparticles that can dynamically respond to conditions in the body by altering their surfaces or other properties, much like proteins do in nature. This may help them to avoid being filtered out by organs such as the liver, but at the same time to have the optimal properties needed to enter tumors.

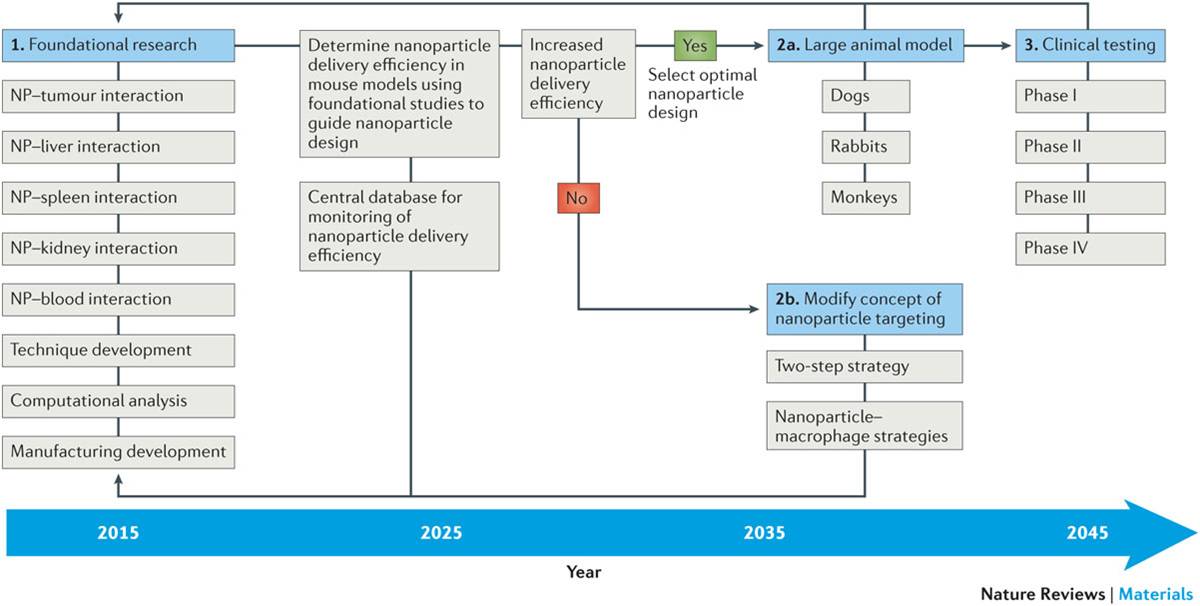

More generally, the authors argue that, in order to increase nanoparticle delivery efficiency, a systematic and coordinated long-term strategy is necessary. To build a strong foundation for the field of cancer nanomedicine, researchers will need to understand a lot more about the interactions between nanoparticles and the body’s various organs than they do today. To this end, Chan’s lab has developed techniques to visualize these interactions across whole organs using 3D optical microscopy, a study published in ACS Nano this week.

In addition to this, the team has set up an open online database, called the Cancer Nanomedicine Repository that will enable the collection and analysis of data on nanoparticle delivery efficiency from any study, no matter where it is published. The team has already uploaded the data gathered for the latest paper, but when the database goes live in June, researchers from all over the world will be able to add their data and conduct real-time analysis for their particular area of interest.

“It is a big challenge to collect and find ways to summarize data from a decade of research but this article will be immensely useful to researchers in the field,” says Professor Julie Audet (IBBME), a collaborator on the study.

Wilhelm says there is a long way to go in order to improve the clinical translation of cancer nanomedicines, but he’s optimistic about the results. “From the first publication on liposomes in 1965 to when they were first approved for use in treating cancer, it took 30 years,” he says. “In 2016, we already have a lot of data, so there’s a chance that the translation of new cancer nanomedicines for clinical use could go much faster this time. Our meta-analysis provides a ‘reality’ check of the current state of cancer nanomedicine and identifies the specific areas of research that need to be investigated to ensure that there will be a rapid clinical translation of nanomedicine developments.”

I made time to read this paper,

Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours by Stefan Wilhelm, Anthony J. Tavares, Qin Dai, Seiichi Ohta, Julie Audet, Harold F. Dvorak, & Warren C. W. Chan. Nature Reviews Materials 1, Article number: 16014 (2016 doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2016.14 Published online: 26 April 2016

It appears to be open access.

The paper is pretty accessible but it does require that you have some tolerance for your own ignorance (assuming you’re not an expert in this area) and time. If you have both, you will find a good description of the various pathways scientists believe nanoparticles take to enter a tumour. In short, they’re not quite sure how nanoparticles gain entry. As well, there are discussions of other problems associated with the field such as producing enough nanoparticles for general usage.

More than an analysis, there’s also a proposed plan for future action (from Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours ),

Current research in using nanoparticles in vivo has focused on innovative design and demonstration of utility of these nanosystems for imaging and treating cancer. The poor clinical translation has encouraged the researchers in the field to investigate the effect of nanoparticle design (for example, size, shape and surface chemistry) on its function and behaviour in the body in the past 10 years. From a cancer-targeting perspective, we do not believe that nanoparticles will be successfully translated to human use if the current ‘research paradigm’ of nanoparticle targeting continues because the delivery efficiency is too low. We propose a long-term strategy to increase the delivery efficiency and enable nanoparticles to be translated to patient care in a cost-effective manner from the research stage. A foundation for the field will be built by obtaining a detailed view of nanoparticle–organ interaction during nanoparticle transport to the tumour, using computational strategies to organize and simulate the results and the development of new tools to assess nanoparticle delivery. In addition, we propose that these results should be collected in a central database to allow progress in the field to be monitored and correlations to be established. A 30-year strategy was proposed and seemed to be a reasonable time frame because the first liposome system was reported in 1965 (Ref. 122) and the first liposome formulation (Doxil) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995 (Refs 91,92). This 30-year time frame may be shortened as a research foundation has already been established but only if the community can parse the immense amount of currently published data. NP, nanoparticle.

Another paper was mentioned in the news release,

Three-Dimensional Optical Mapping of Nanoparticle Distribution in Intact Tissues by Shrey Sindhwani, Abdullah Muhammad Syed, Stefan Wilhelm, Dylan R Glancy, Yih Yang Chen, Michael Dobosz, and Warren C.W. Chan.ACS Nano, Just Accepted Manuscript Publication Date (Web): April 21, 2016 DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b01879

Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

Finally, Melanie Ward in an April 26, 2016 article for Science News Hub has another approach to describing the research. Oddly, she states this,

However, the study warns about the lack of efficiency despite major economic investments (more than one billion dollars in the US in the past decade).

She’s right; the US has spent more than $1B in the last decade. In fact, they’ve allocated over $1B every year to the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI) for almost two decades for a total of more than $20B. You might want to apply some caution when reading. BTW, I think that’s a wise approach for everything you read including the blog postings here.