This is a little outside my comfort zone but here goes anyway. From a December 23, 2020 news item on phys.org (Note: Links have been removed),

Osaka City University scientists have developed mathematical formulas to describe the current and fluctuations of strongly correlated electrons in quantum dots. Their theoretical predictions could soon be tested experimentally.

Theoretical physicists Yoshimichi Teratani and Akira Oguri of Osaka City University, and Rui Sakano of the University of Tokyo have developed mathematical formulas that describe a physical phenomenon happening within quantum dots and other nanosized materials. The formulas, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, could be applied to further theoretical research about the physics of quantum dots, ultra-cold atomic gasses, and quarks.

At issue is the Kondo effect. This effect was first described in 1964 by Japanese theoretical physicist Jun Kondo in some magnetic materials, but now appears to happen in many other systems, including quantum dots and other nanoscale materials.

…

A December 23, 2020 Osaka City University press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

Normally, electrical resistance drops in metals as the temperature drops. But in metals containing magnetic impurities, this only happens down to a critical temperature, beyond which resistance rises with dropping temperatures.

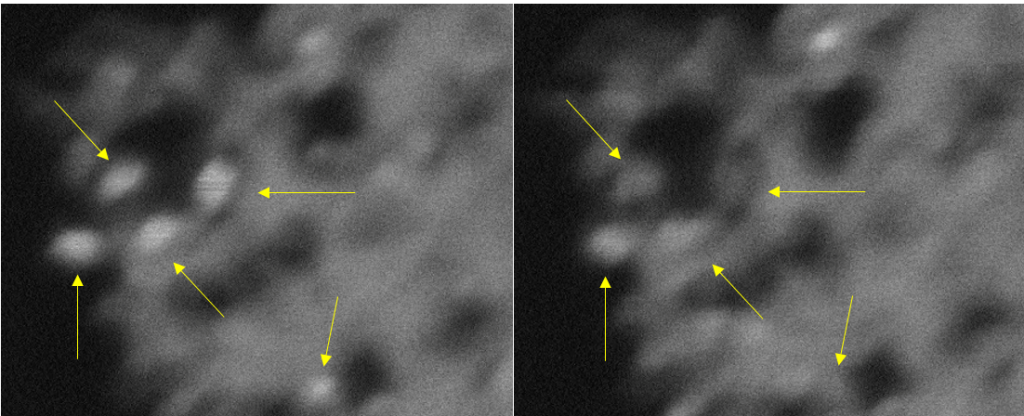

Scientists were eventually able to show that, at very low temperatures near absolute zero, electron spins become entangled with the magnetic impurities, forming a cloud that screens their magnetism. The cloud’s shape changes with further temperature drops, leading to a rise in resistance. This same effect happens when other external ‘perturbations’, such as a voltage or magnetic field, are applied to the metal.

Teratani, Sakano and Oguri wanted to develop mathematical formulas to describe the evolution of this cloud in quantum dots and other nanoscale materials, which is not an easy task.

To describe such a complex quantum system, they started with a system at absolute zero where a well-established theoretical model, namely Fermi liquid theory, for interacting electrons is applicable. They then added a ‘correction’ that describes another aspect of the system against external perturbations. Using this technique, they wrote formulas describing electrical current and its fluctuation through quantum dots.

Their formulas indicate electrons interact within these systems in two different ways that contribute to the Kondo effect. First, two electrons collide with each other, forming well-defined quasiparticles that propagate within the Kondo cloud. More significantly, an interaction called a three-body contribution occurs. This is when two electrons combine in the presence of a third electron, causing an energy shift of quasiparticles.

“The formulas’ predictions could soon be investigated experimentally”, Oguri says. “Studies along the lines of this research have only just begun,” he adds.

The formulas could also be extended to understand other quantum phenomena, such as quantum particle movement through quantum dots connected to superconductors. Quantum dots could be a key for realizing quantum information technologies, such as quantum computers and quantum communication.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Fermi Liquid Theory for Nonlinear Transport through a Multilevel Anderson Impurity by Yoshimichi Teratani, Rui Sakano, and Akira Oguri. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 216801 (Issue Vol. 125, Iss. 21 — 20 November 2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.216801 Published Online: 17 November 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.