Take a mathematician (L. Mahadevan), a physicist (Andrzej Herczynski), and an art historian (Claude Cernuschi) and you’re liable to get a different perspective on Jackson Pollock*, a major figure in abstract expressionism, art. (I’m pretty sure there’s a joke in there of the: “There was mathematician and a physicist in a bar when an art historian came in …” ilk. I just can’t come up with it. If you can, please do leave it in the comments.)

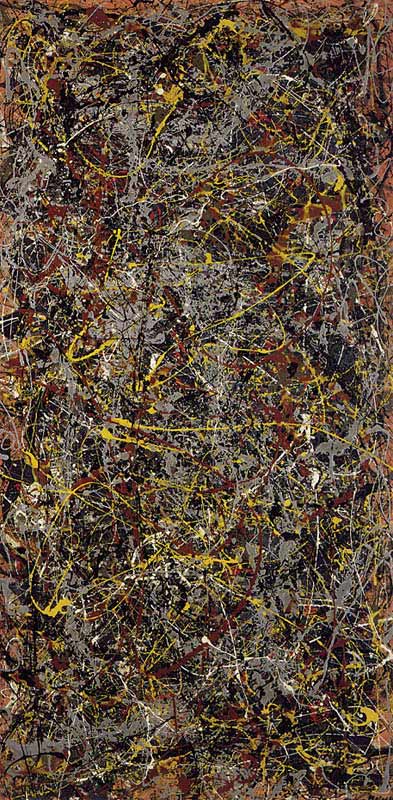

Let’s start with a picture (image downloaded from the Wikipedia essay about Jackson Pollock’s No. 5, 1948),

In a recent paper published in Physics Today (Painting with drops, jets, and sheets, which is behind a paywall), Mahadevan, Herczynski, and Cernuschi speculate about Pollock’s intuitive understanding of physics, in this case, fluid dynamics. From the June 28, 2011 news item on physorg.com,

A quantitative analysis of Pollock’s streams, drips, and coils, by Harvard mathematician L. Mahadevan and collaborators at Boston College, reveals, however, that the artist had to be slow—he had to be deliberate—to exploit fluid dynamics in the way that he did.

The finding, published in Physics Today, represents a rare collision between mathematics, physics, and art history, providing new insight into the artist’s method and techniques—as well as his appreciation for the beauty of natural phenomena.

…

“My own interest,” says Mahadevan, “is in the tension between the medium—the dynamics of the fluid, and the way it is applied (written, brushed, poured…)—and the message. While the latter will eventually transcend the former, the medium can be sometimes limiting and sometimes liberating.”

Pollock’s signature style involved laying a canvas on the floor and pouring paint onto it in continuous, curving streams. Rather than pouring straight from the can, he applied paint from a stick or a trowel, waving his hand back and forth above the canvas and adjusting the height and angle of the trowel to make the stream of paint wider or thinner.

Simultaneously restricted and inspired by the laws of nature, Pollock took on the role of experimentalist, ceding a certain amount of control to physics in order to create new aesthetic effects.

…

The artist, of course, must have discovered the effects he could create through experimentation with various motions and types of paint, and perhaps some intuition and luck. But that, says Mahadevan, is the essence of science: “We are all students of nature, and so was Pollock. Often, artists and artisans are far ahead, as they push boundaries in ways that are quite similar to, and yet different from, how scientists and engineers do the same.”

There’s more about this study on the physorg.com site including a video illustrating fluid dynamics. You can also find a June 29, 2011 news item on Science Daily and a June 29, 2011 article in Harvard Magazine about the study. From the Harvard news article,

MODERN ART WAS NEVER more famously lampooned than when Tom Stoppard [playwright and screenwriter] said, “Skill without imagination is craftsmanship and gives us many useful objects such as wickerwork picnic baskets. Imagination without skill gives us modern art.”

The article by expanding on Mahadevan’s research gives the lie to Stoppard’s quote. (I wonder if Stoppard will write a play about physics and art in the light of this new thinking about Pollock’s work?)

This all brought to mind, Richard Jackson’s work which was featured in 2010 at the Rennie Collection in Vancouver (my most substantive comments about Jackson’s work are in my May 11, 2010 posting). Trained as both an artist and an engineer, he too works with paint and its vicosity. I still remember the piece in the gallery basement that featured three (as I recall) cans of paint apparently caught in the act of being poured. In retrospect, one of the things I liked best about the show is that a lot of Jackson’s work is very much about the physical act of painting and the physicality of the materials.

One final note, the L. in Mahadevan’s name stands for Lakshinarayan.

*’Pollock’s’ corrected to Pollock on April 27, 2017.