Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences researchers discovered some unexpected properties when testing a new coating according to an Oct. 22, 2013 news item on Azonano,

Active camouflage has taken a step forward at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), with a new coating that intrinsically conceals its own temperature to thermal cameras.

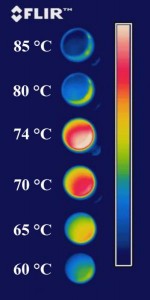

In a laboratory test, a team of applied physicists placed the device on a hot plate and watched it through an infrared camera as the temperature rose. Initially, it behaved as expected, giving off more infrared light as the sample was heated: at 60 degrees Celsius it appeared blue-green to the camera; by 70 degrees it was red and yellow. At 74 degrees it turned a deep red—and then something strange happened. The thermal radiation plummeted. At 80 degrees it looked blue, as if it could be 60 degrees, and at 85 it looked even colder. Moreover, the effect was reversible and repeatable, many times over.

The Oct. 21, 2013 Harvard University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, discusses the potential for this discovery and describes the process of discovery in more detail (Note: A link has been removed),

Principal investigator Federico Capasso, Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at Harvard SEAS, predicts that with only small adjustments the coating could be used as a new type of thermal camouflage or as a kind of encrypted beacon to allow soldiers to covertly communicate their locations in the field.

The secret to the technology lies within a very thin film of vanadium oxide, an unusual material that undergoes dramatic electronic changes when it reaches a particular temperature. At room temperature, for example, pure vanadium oxide is electrically insulating, but at slightly higher temperatures it transitions to a metallic, electrically conductive state. During that transition, the optical properties change, too, which means special temperature-dependent effects—like infrared camouflage—can also be achieved.

The insulator-metal transition has been recognized in vanadium oxide since 1959. However, it is a difficult material to work with: in bulk crystals, the stress of the transition often causes cracks to develop and can shatter the sample. Recent advances in materials synthesis and characterization—especially those by coauthor Shriram Ramanathan, Associate Professor of Materials Science at Harvard SEAS—have allowed the creation of extremely pure samples of thin-film vanadium oxide, enabling a burst of new science and engineering to take off in just the last few years.

“Thanks to these very stable samples that we’re getting from Prof. Ramanathan’s lab, we now know that if we introduce small changes to the material, we can dramatically change the optical phenomena we observe,” explains lead author Mikhail Kats, a graduate student in Capasso’s group at Harvard SEAS. “By introducing impurities or defects in a controlled way via processes known as doping, modifying, or straining the material, it is possible to create a wide range of interesting, important, and predictable behaviors.”

By doping vanadium oxide with tungsten, for example, the transition temperature can be brought down to room temperature, and the range of temperatures over which the strange thermal radiation effect occurs can be widened. Tailoring the material properties like this, with specific outcomes in mind, may enable engineering to advance in new directions.

The researchers say a vehicle coated in vanadium oxide tiles could potentially mimic its environment like a chameleon, appearing invisible to an infrared camera with only very slight adjustments to the tiles’ actual temperature—a far more efficient system than the approaches in use today.

Tuned differently, the material could become a component of a secret beacon, displaying a particular thermal signature on cue to an infrared surveillance camera. Capasso’s team suggests that the material could be engineered to operate at specific wavelengths, enabling simultaneous use by many individually identifiable soldiers.

And, because thermal radiation carries heat, the researchers believe a similar effect could be employed to deliberately speed up or slow down the cooling of structures ranging from houses to satellites.

The Harvard team’s most significant contribution is the discovery that nanoscale structures that appear naturally in the transition region of vanadium oxide can be used to provide a special level of tunability, which can be used to suppress thermal radiation as the temperature rises. The researchers refer to such a spontaneously structured material as a “natural, disordered metamaterial.”

“To artificially create such a useful three-dimensional structure within a material is extremely difficult,” says Capasso. “Here, nature is giving us what we want for free. By taking these natural metamaterials and manipulating them to have all the properties we want, we are opening up a new area of research, a completely new direction of work. We can engineer new devices from the bottom up.”

Here’s an image, from the scientists, illustrating the material’s thermal camouflage (or chameleon) properties,

A new coating intrinsically conceals its own temperature to thermal cameras. (Image courtesy of Mikhail Kats.)

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Vanadium Dioxide as a Natural Disordered Metamaterial: Perfect Thermal Emission and Large Broadband Negative Differential Thermal Emittance by Mikhail A. Kats, Romain Blanchard, Shuyan Zhang, Patrice Genevet, Changhyun Ko, Shriram Ramanathan, and Federico Capasso. Phys. Rev. X » Volume 3 » Issue 4 or Phys. Rev. X 3, 041004 (2013) DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.3.041004

This paper is published in an open access journal according to the Harvard news release,

About Physical Review X

Launched in August 2011, PRX (http://prx.aps.org) is an open-access, peer-reviewed publication of the American Physical Society (www.aps.org), a non-profit membership organization working to advance and diffuse the knowledge of physics through its outstanding research journals, scientific meetings, and education, outreach, advocacy and international activities. APS represents 50,000 members, including physicists in academia, national laboratories and industry in the United States and throughout the world.