A Sept. 28,2017 news item on Nanowerk announces a portable, inexpensive sensor for drugs (Note: A link has been renewed),

Speed, uppers, chalk, glass, crystal, or whatever you prefer to call them, can be instantly detected from biological fluids with a new portable kit that costs as little as $50. Scientists at the Center for Self-Assembly and Complexity, within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS, South Korea), in collaboration with Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), have devised the first methamphetamine and amphetamine sensor that can detect minute concentrations of these drugs from a single drop of urine in real-time.

Published in the journal Chem (“Point-of-Use Detection of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants with Host-Molecule-Functionalized Organic Transistors”), this simple and flexible sensor, which can be attached to a wristband and connected to an Android app via Bluetooth, could move drug screening from the labs to the streets.

A Sept. 28 (?), 2017 IBS press release by Letizia Diamante (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

Easy to synthesize and cheaper than heroin or cocaine, amphetamine-based drugs are the most abused drugs in the world, after cannabis. Conventional drug detection methods require a long time, as the sample must be taken into a lab for the analysis. It also needs experts to run the expensive equipment. The technology reported in this study is instead small, portable, cheap, fast and easy to use.

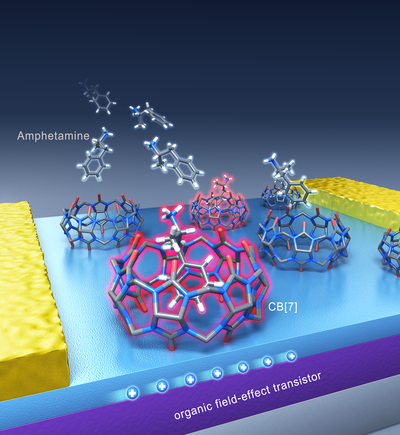

The idea for this technology came from the IBS chemist HWANG Ilha: “I was watching a TV news report on the usage of illegal drugs, and I thought to check what the chemical structure of methamphetamine looks like.” Soon after, the scientist anticipated that the drug would form a tight complex with a family of hollow pumpkin-shaped molecules, called cucurbituril (CB) members. The team then discovered that cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7])’s empty cavity binds well with amphetamine-based drugs and can be used as the drug recognition unit of a sensor. Cucurbiturils’ hollow chamber has already been studied for various technological uses, but this is the first device application in amphetamine-based drug detection.

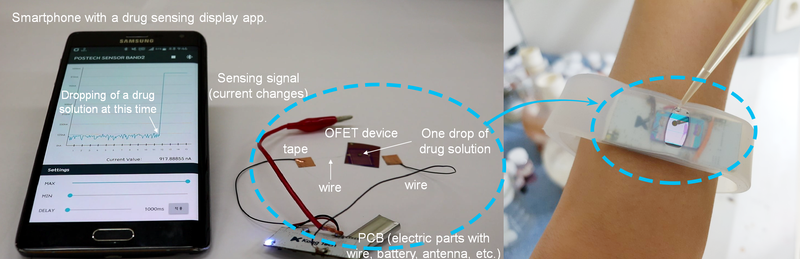

▲ Figure 1: Wireless sensor for amphetamine-based drug detection.The kit is made of an organic field-effect transistor (OFET) device, an electric circuit board with a rechargeable battery and an antenna. The OFET device surface is coated with CB[7], whose function is to bind amphetamine and methamphetamine drugs in solution. The binding event is instantly converted to current, whose magnitude is proportional to the concentration of the drug. The app on the smartphone shows a peak as soon as a drop of urine with the drug is applied to the device. Moreover the entire kit can fit in a handy wristband.

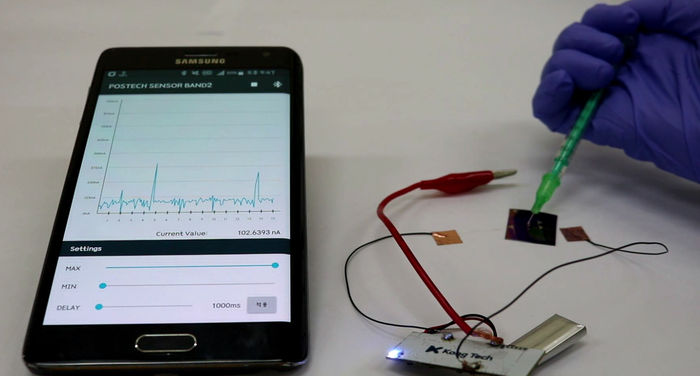

▲ Video 1: The detector in action. [Click text not image]

As soon as a drop of water with 0.0001 ng/mL (1 pM) of amphetamine is applied to the kit, the app shows a peak in current proportional to the concentration of drug. When the liquid is removed, the current level goes back to baseline, and the sensor can be reused. (Modified from Jang et al, Chem 2017)Combining a transistor coated with CB[7], flexible materials, rechargeable batteries and a Bluetooth antenna, the research team developed a detector wristband connected to an app. In the presence of the drug, the molecular recognition between CB[7] and the drug molecule triggers an electrical signal which appears as a peak on the smartphone screen.

Current drug detection based on immunoassay or liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry techniques has a detection limit of about 10 ng/mL. On the contrary, the sensitivity of this new sensor is about 0.0001 ng/mL in water and 0.1 ng/mL in urine. Therefore, it is expected that this method will allow the detection of drug molecules in biological fluids, like urine and sweat, for a longer time after drug consumption.

▲ Figure 2: Graphic representation of the drug detection platform.Binding of drug molecules to the hollow cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7])’s cavity changes the current signal flowing in the transistor and therefore can be used as a detection system. The molecular structure of amphetamine and methamphetamine bound to cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]) was confirmed with X-ray crystallography. Each color indicates a different atom (blue: nitrogen, red: oxygen, gray: carbon, and white: hydrogen). CB[7]’s hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

▲ Figure 3: Humorous view of the pumpkin-shaped molecule, cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]), able to bind and detect amphetamine and methamphetamine molecules.(Credits: Modified from Titusurya – Freepik.com)“Real time detection of amphetamine drugs on location would bring a big change to society,” explains another corresponding author KIM Kimoon. “In the same way as police can use a breathalyzer to detect alcohol on the spot, we aim to achieve the same with this device.”

False positives cannot be excluded yet, as urine contains a rich mixture of proteins and other metabolites that could affect the reading. Therefore, before commercializing it, clinical trials with drug users’ biological fluids are necessary. The researchers have patented the technology and they will continue to do further research in the near future.s

“Combining basic science with the latest technology, we can expect that this research will also lead to other new sensors, useful for our daily life,” concludes the third corresponding author OH Joon Hak. Indeed, the team is also keen on developing sensors for other kinds of drugs, as well as kits for the detection of dangerous substances, environmental monitoring, healthcare and safety.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Point-of-Use Detection of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants with Host-Molecule-Functionalized Organic Transistors by Yoonjung Jang, Moonjeong Jang, Hyoeun Kim, Sang Jin Lee, Eunyeong Jin, Jin Young Koo, In-Chul Hwang, Yonghwi Kim, Young Ho Ko, Ilha Hwang., Joon Hak Oh, Kimoon Kim. Chem (2017). DOI: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.08.015 Publication stage: In Press Corrected Proof

This paper appears to be behind a paywall.