The Nanocar Race (which at one point was the NanoCar Race) took place on April 28 -29, 2017 in Toulouse, France. Presumably the fall 2016 race did not take place (as I had reported in my May 26, 2016 posting). A March 23, 2017 news item on ScienceDaily gave the latest news about the race,

Nanocars will compete for the first time ever during an international molecule-car race on April 28-29, 2017 in Toulouse (south-western France). The vehicles, which consist of a few hundred atoms, will be powered by minute electrical pulses during the 36 hours of the race, in which they must navigate a racecourse made of gold atoms, and measuring a maximum of a 100 nanometers in length. They will square off beneath the four tips of a unique microscope located at the CNRS’s Centre d’élaboration de matériaux et d’études structurales (CEMES) in Toulouse. The race, which was organized by the CNRS, is first and foremost a scientific and technological challenge, and will be broadcast live on the YouTube Nanocar Race channel. Beyond the competition, the overarching objective is to advance research in the observation and control of molecule-machines.

More than just a competition, the Nanocar Race is an international scientific experiment that will be conducted in real time, with the aim of testing the performance of molecule-machines and the scientific instruments used to control them. The years ahead will probably see the use of such molecular machinery — activated individually or in synchronized fashion — in the manufacture of common machines: atom-by-atom construction of electronic circuits, atom-by-atom deconstruction of industrial waste, capture of energy…The Nanocar Race is therefore a unique opportunity for researchers to implement cutting-edge techniques for the simultaneous observation and independent maneuvering of such nano-machines.

The experiment began in 2013 as part of an overview of nano-machine research for a scientific journal, when the idea for a car race took shape in the minds of CNRS senior researcher Christian Joachim (now the director of the race) and Gwénaël Rapenne, a Professor of chemistry at Université Toulouse III — Paul Sabatier. …

An April 19, 2017 article by Davide Castelvecchi for Nature (magazine) provided more detail about the race (Note: Links have been removed),

The term nanocar is actually a misnomer, because the molecules involved in this race have no motors. (Future races may incorporate them, Joachim says.) And it is not clear whether the molecules will even roll along like wagons: a few designs might, but many lack axles and wheels. Drivers will use electrons from the tip of a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) to help jolt their molecules along, typically by just 0.3 nano-metres each time — making 100 nanometres “a pretty long distance”, notes physicist Leonhard Grill of the University of Graz, Austria, who co-leads a US–Austrian team in the race.

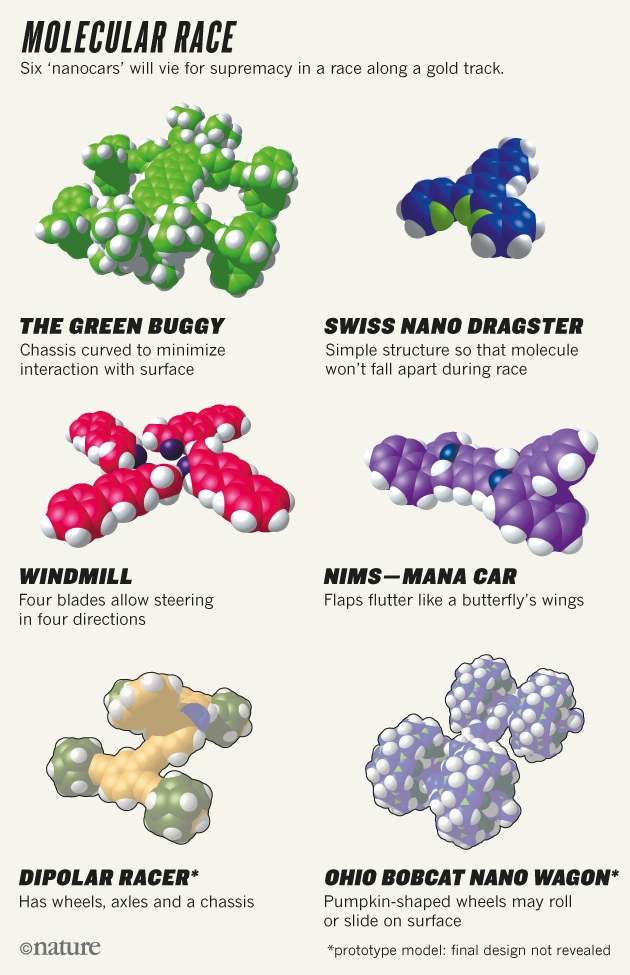

Contestants are not allowed to directly push on their molecules with the STM tip. Some teams have designed their molecules so that the incoming electrons raise their energy states, causing vibrations or changes to molecular structures that jolt the racers along. Others expect electrostatic repulsion from the electrons to be the main driving force. Waka Nakanishi, an organic chemist at the National Institute for Materials Science in Tsukuba, Japan, has designed a nanocar with two sets of ‘flaps’ that are intended to flutter like butterfly wings when the molecule is energized by the STM tip (see ‘Molecular race’). Part of the reason for entering the race, she says, was to gain access to the Toulouse lab’s state-of-the-art STM to better understand the molecule’s behaviour.

Eric Masson, a chemist at Ohio University in Athens, hopes to find out whether the ‘wheels’ (pumpkin-shaped groups of atoms) of his team’s car will roll on the surface or simply slide. “We want to better understand the nature of the interaction between the molecule and the surface,” says Masson..

Adapted from www.nanocar-race.cnrs.fr

Simply watching the race progress is half the battle. After each attempted jolt, teams will take three minutes to scan their race track with the STM, and after each hour they will produce a short animation that will immediately be posted online. That way, says Joachim, everyone will be able to see the race streamed almost live.

Nanoscale races

…

The Toulouse laboratory has an unusual STM with four scanning tips — most have only one — that will allow four teams to race at the same time, each on a different section of the gold surface. Six teams will compete this week to qualify for one of the four spots; the final race will begin on 28 April at 11 a.m. local time. The competitors will face many obstacles during the contest. Individual molecules in the race will often be lost or get stuck, and the trickiest part may be to negotiate the two turns in the track, Joachim says. He thinks the racers may require multiple restarts to cover the distance.

For anyone who wants more information, go to the Nanocar Race website. There is also a highlights video,

The best moments of the first-ever international race of molecule- cars.