I’m going to start with the ‘more’.

Deadline extended

From an October 12, 2023 Canadian Science Policy Centre (CSPC) announcement received via email,

Science Meets Parliament 2024

Application Deadline is Nov 9th!You still have some time, the deadline to submit your applications for Science Meets Parliament 2024, is Thursday, Nov 9th [2023]! To apply, click here..

Science Meets Parliament (SMP) is a program that works to strengthen the connections between the science and policy communities. This program is open to Tier II Canada Research Chairs, Indigenous Principal Investigators, and Banting Postdoctoral Fellows.

Two events: October 13, 2023 and October 24, 2023

From an October 12, 2023 Canadian Science Policy Centre (CSPC) announcement,

Upcoming Virtual Panel [Canada-Brazil Cooperation and Collaboration in STI [Science, Technology, and Innovation]]

This virtual panel aims to discuss the ongoing Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) cooperation between Brazil and Canada, along with the potential for furthering this relationship. The focus will encompass strategic areas of contact, ongoing projects, and scholarship opportunities. It is pertinent to reflect on the science diplomacy efforts of each country and their reciprocal influence. Additionally, the panel aims to explore how Canada engages with developing countries in terms of STI.

Please note the panel date has been changed to October 13th at 12pm EST. Click the button below to register for the upcoming virtual panel!

Register Here

An event to mark a CSPC research report,

Report Launch on The Hill!

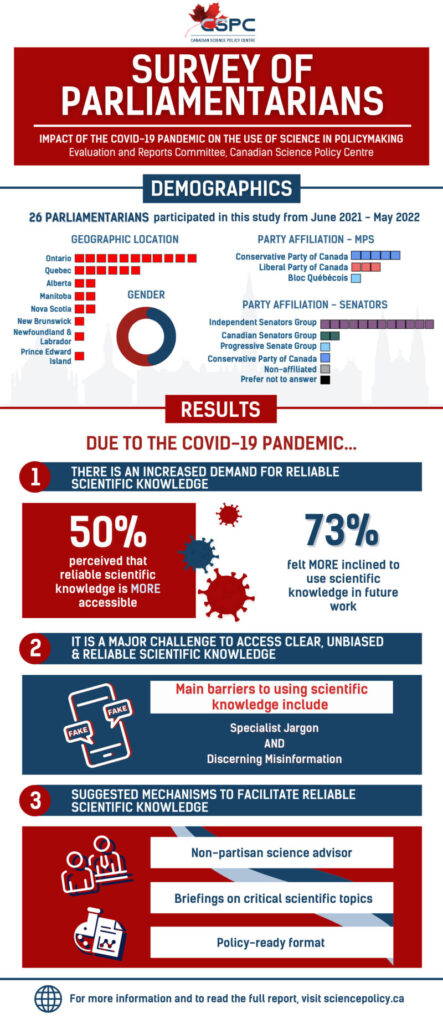

CSPC Survey of Parlimentarians!CSPC has organized a panel discussion on Oct 24th [2023] at 8 AM [EST] on Parliament Hill to launch the results of the project: “Survey of Parliamentarians on the Impact of the Pandemic on the Use of Science in Policy Making”.

This project was conducted by the CSPC’s Evaluation and Reports Committee, which began the dissemination of the survey to parliamentarians in 2021. The objective was to gather information on the impact of the pandemic on the use of science in policy-making. Survey responses were analyzed and a full report is going to be presented and publicized.

More information about the survey and the Final Report on the Survey of Parliamentarians can be found HERE.

To attend this in-person event, please click the button below.

Register Here

Funky or not? Final Report on the Survey of Parliamentarians

Wouldn’t it have been surprising if the survey results had shown that parliamentarians weren’t interested in getting science information when developing science policies? Especially surprising given that the survey was developed, conducted, and written up by the Canadian Science Policy Centre.

While there is a lot of interesting material, I really wish the authors had addressed the self-serving nature of this survey in their report. To their credit they do acknowledge some of the shortcomings, from the report (PDF), here’s the conclusion, Note: All emphases are mine,

There was near unanimous agreement by parliamentarians that there is a need for scientific knowledge in an accessible and policy-ready format. Building upon that, and taking into account the difficulties that parliamentarians identified in acquiring scientific knowledge to support policy- making, there were two main facilitators suggested by participants that may improve timely and understandable scientific knowledge in parliamentarian work. Firstly, the provision of scientific knowledge in a policy-ready format through a non-partisan science advice mechanism such as a non-partisan science advisor for the House of Commons and Senate. Secondly, research

summaries in an accessible format and/or briefing of hot scientific topics provided by experts. As parliamentarians revealed in this survey, there is a clear desire to use scientific knowledge more frequently as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the scientific community has an opportunity to support parliamentarians in this regard through mechanisms such as those indicated here.Notwithstanding, the findings above come with some limitations within this study. First, the committee acknowledges that due to the small sample size of survey participants – particularly for MPs – the results presented in this report may not be representative of the parliamentarians of the 43rd Canadian Parliament. The committee also acknowledges that this limitation is further compounded by incomplete demographic representation. Although the committee made great efforts to achieve a survey demographic across gender, party affiliation, geographical location, and language that was representative of the 43rd Canadian Parliament, there were certain demographics that were ultimately under-represented. For these reasons, trends highlighted in this report and comparisons between MPs and senators should be interpreted with these limitations in mind. Finally, the committee acknowledged the possibility that the data presented in this report may be biased towards more positive perceptions of scientific knowledge, since this survey was more likely to have been completed by parliamentarians who have an interest in science. Even with these limitations, this study provides a critical step forward in understanding parliamentarians’ needs regarding acquisition of scientific knowledge in their work and proposing possible mechanisms to support these needs.

In conclusion, the current report reveals that parliamentarians’ inclination to use science in policy-making has increased in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, parliamentarians are more aware than ever of the necessity for accurate and accessible scientific knowledge in their work. There are clear challenges facing the use of scientific knowledge in policy-making, namely misinformation and disinformation, but participants highlighted different key proposed mechanisms that can better integrate science and research into the framework of public policy. [p. 34]

Self-selection (“more likely to have been completed by parliamentarians who have an interest in science”) is always a problem. As for geographical representation, no one from BC, Saskatchewan, the Yukon, Nunavut, or the Northwest Territories responded.

Intriguingly, there were 18 Senators and 8 MP (members of Parliament) for a total of 26 respondents (see pp. 15-16 in the report [PDF] for more about the demographics).

As the authors note, it’s a small number of respondents. which seems even smaller when you realize there are supposed to be 338 MPs (House of Commons of Canada Wikipedia entry) and 105 Senators (List of current senators of Canada Wikipedia entry).

I wish they had asked how long someone had served in Parliament. (Yes, a bit tricky when an MP is concerned but perhaps asking for a combined total would solve the problem.)

While I was concerned about the focus on COVID-19 and the generic sounding references to ‘scientific knowledge’, my concerns were somewhat appeased with this, from the report (PDF),

Need for different types of scientific knowledge

The committee found that across all participants, there was an increased need for all listed types of scientific knowledge by the majority of participants. One parliamentarian elaborated on this, highlighting that several Bills have touched on these areas over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and that in their research work, parliamentarians have had to refer to these areas of scientific knowledge regularly.

Unsurprisingly, the type of scientific knowledge reported to have the largest increase in need was health sciences (85%). Notably, 4% or less of participants indicated a lesser need for all types of scientific knowledge, with health science, social science and humanities, and natural sciences and engineering seeing no decline in need by participants. Both MP and senator participants reported a greater need for research and evidence in health sciences (e.g., public health, vaccine research , cancer treatment etc.), social sciences and humanities (e.g., psychology, sociology, law, ethics), and environmental sciences (e.g., climate, environment, earth studies) as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly, one parliamentarian reflected that there is an increased need among policy- makers to be objective and listen to scientists, as well as scientific data and evidence in areas such as public health and climate change. However, the relative increase in need for each subject between groups was different. For instance, senator participants reported the largest increase in need for health sciences (89%), followed by environmental science (78%) and social sciences and humanities (73%); whereas MP participants reported the largest increase in need for social sciences and humanities (88%), followed by health sciences (75%) and environmental science (63%).

…

Economics, Indigenous Knowledge, and natural sciences and engineering (e.g., biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, engineering) had smaller increases in need for both MPs and senators. For both groups, natural sciences and engineering saw 50% of participants indicate an increase in need. In the case of economics and Indigenous Knowledge, senators noted a larger increase in need for these fields compared to MPs. In particular, in the case of Indigenous Knowledge only 37% of MPs

reported an increased need for this type of scientific knowledge compared to 61% of senators.Finally, one parliamentarian noted that climate change and Indigenous issues have gained a greater prominence since the pandemic, but not necessarily as a result of it. Therefore, in addition to putting these responses in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, these responses should also be considered in the context of other global and Canadian issues that arose over the course of this survey (Question 4, Annex A [Cannot find any annexes]). [pp. 21-22]

Interesting to read (although I seem to have stumbled onto the report early as it’s no longer available as of October 13, 2023 at 10:10 am PT) from the “Survey of Parliamentarians: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of science in policymaking” CSPC webpage.

As for funky, I think you need to be really clear that you’re aware your report can readily be seen as self-serving and note what steps you’ve taken to address the issue.