A May 3, 2017 news item on Nanowerk announces research from Japan on using tumor suppressor proteins to control nanostructures,

A new method combining tumor suppressor protein p53 and biomineralization peptide BMPep successfully created hexagonal silver nanoplates, suggesting an efficient strategy for controlling the nanostructure of inorganic materials.

Precise control of nanostructures is a key factor to form functional nanomaterials. Biomimetic approaches are considered effective for fabricating nanomaterials because biomolecules are able to bind with specific targets, self-assemble, and build complex structures. Oligomerization, or the assembly of biomolecules, is a crucial aspect of natural materials that form higher-ordered structures.

A May 3,2017 Hokkaido University research press release, which originated the news item, delves into the details,

Some peptides are known to bind with a specific inorganic substance, such as silver, and enhance its crystal formation. This phenomenon, called peptide-mediated biomineralization, could be used as a biomimetic approach to create functional inorganic structures. Controlling the spatial orientation of the peptides could yield complex inorganic structures, but this has long been a great challenge.

A team of researchers led by Hokkaido University Professor Kazuyasu Sakaguchi has succeeded in controlling the oligomerization of the silver biomineralization peptide (BMPep) which led to the creation of hexagonal silver nanoplates.

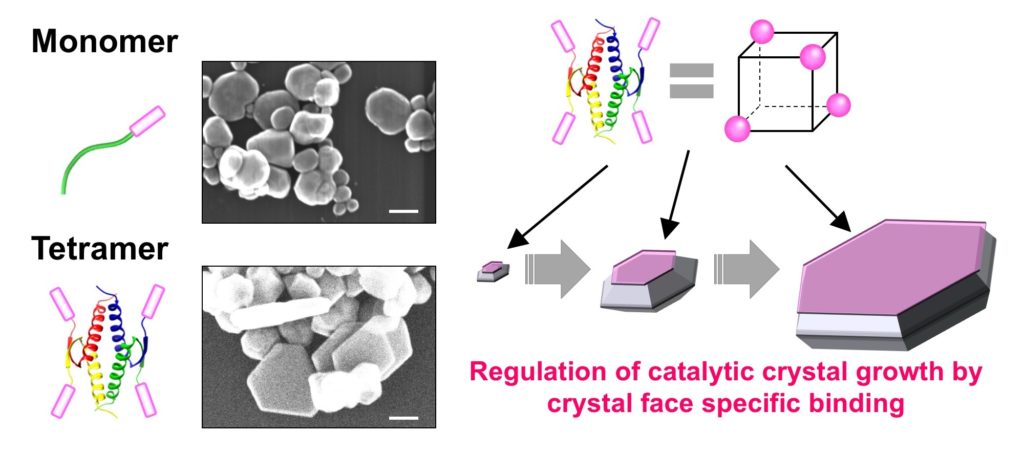

The team utilized the well-known tumor suppressor protein p53 which has been known to form tetramers through its tetramerization domain (p53Tet). “The unique symmetry of the p53 tetramer is an attractive scaffold to be used in controlling the overall oligomerization state of the silver BMPep such as its spatial orientation, geometry, and valency,” says Sakaguchi.

In the experiments, the team successfully created silver BMPep fused with p53Tet. This resulted in the formation of BMPep tetramers which yielded hexagonal silver nanoplates. They also found that the BMPep tetramers have enhanced specificity to the structured silver surface, apparently regulating the direction of crystal growth to form hexagonal nanoplates. Furthermore, the tetrameric peptide acted as a catalyst, controlling the silver’s crystal growth without consuming the peptide.

“Our novel method can be applied to other biomineralization peptides and oligomerization proteins, thus providing an efficient and versatile strategy for controlling nanostructures of various inorganic materials. The production of tailor-made nanomaterials is now more feasible,” Sakaguchi commented.

(Left panels) Schematic illustrations of monomeric and tetrameric biomineralization peptides fused with p53Tet and electron microscopy images of silver nanostructures formed by the biomineralization peptides. Scale bar = 100 nm. (Right) The proposed model in which tetrameric biomineralization peptides regulate the direction of crystal growth and therefore its nanostructure.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Oligomerization enhances the binding affinity of a silver biomineralization peptide and catalyzes nanostructure formation by Tatsuya Sakaguchi, Jose Isagani B. Janairo, Mathieu Lussier-Price, Junya Wada, James G. Omichinski, & Kazuyasu Sakaguchi. Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 1400 (2017) doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01442-8 Published online: 03 May 2017

This paper is open access.