Despite all the excitement and claims for nanoparticles as vehicles for drug delivery to ‘sick’ cells there is at least one substantive problem, the drug-laden nanoparticles don’t actually enter the interior of the cell. They are held in a kind of cellular ‘waiting room’.

Leonid Schneider in a Nov. 20, 2015 posting on his For Better Science blog describes the process in more detail,

A large body of scientific nanotechnology literature is dedicated to the biomedical aspect of nanoparticle delivery into cells and tissues. The functionalization of the nanoparticle surface is designed to insure their specificity at targeting only a certain type of cells, such as cancers cells. Other technological approaches aim at the cargo design, in order to ensure the targeted release of various biologically active agents: small pharmacological substances, peptides or entire enzymes, or nucleotides such as regulatory small RNAs or even genes. There is however a main limitation to this approach: though cells do readily take up nanoparticles through specific membrane-bound receptor interaction (endocytosis) or randomly (pinocytosis), these nanoparticles hardly ever truly reach the inside of the cell, namely its nucleocytoplasmic space. Solid nanoparticles are namely continuously surrounded by the very same membrane barrier they first interacted with when entering the cell. These outer-cell membrane compartments mature into endosomal and then lysosomal vesicles, where their cargo is subjected to low pH and enzymatic digestion. The nanoparticles, though seemingly inside the cell, remain actually outside. …

What follows is a stellar piece featuring counterclaims about and including Schneider’s own journalistic research into scientific claims that the problem of gaining entry to a cell’s true interior has been addressed by technologies developed in two different labs.

Having featured one of the technologies here in a July 24, 2015 posting titled: Sticky-flares nanotechnology to track and observe RNA (ribonucleic acid) regulation and having been contacted a couple of times by one of the scientists, Raphaël Lévy from the University of Liverpool (UK), challenging the claims made (Lévy’s responses can be found in the comments section of the July 2015 posting), I thought a followup of sorts was in order.

Scientific debates (then and now)

Scientific debates and controversies are part and parcel of the scientific process and what most outsiders, such as myself, don’t realize is how fraught it is. For a good example from the past, there’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (from its Wikipedia entry), Note: Links have been removed),

Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (published 1985) is a book by Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer. It examines the debate between Robert Boyle and Thomas Hobbes over Boyle’s air-pump experiments in the 1660s.

The style seems more genteel than what a contemporary Canadian or US audience is accustomed to but Hobbes and Boyle (and proponents of both sides) engaged in bruising communication.

There was a lot at stake then and now. It’s not just the power, prestige, and money, as powerfully motivating as they are, it’s the research itself. Scientists work for years to achieve breakthroughs or to add more to our common store of knowledge. It’s painstaking and if you work at something for a long time, you tend to be invested in it. Saying you’ve wasted ten years of your life looking at the problem the wrong way or have misunderstood your data is not easy.

As for the current debate, Schneider’s description gives no indication that there is rancour between any of the parties but it does provide a fascinating view of two scientists challenging one of the US’s nanomedicine rockstars, Chad Mirkin. The following excerpt follows the latest technical breakthroughs to the interior portion of the cell through three phases of the naming conventions (Nano-Flares, also known by its trade name, SmartFlares, which is a precursor technology to Sticky-Flares), Note: Links have been removed,

The next family of allegedly nucleocytoplasmic nanoparticles which Lévy turned his attention to, was that of the so called “spherical nucleic acids”, developed in the lab of Chad Mirkin, multiple professor and director of the International Institute for Nanotechnology at the Northwestern University, USA. These so called “Nano-Flares” are gold nanoparticles, functionalized with fluorophore-coupled oligonucleotides matching the messenger RNA (mRNA) of interest (Prigodich et al., ACS Nano 3:2147-2152, 2009; Seferos et al., J Am. Chem.Soc. 129:15477-15479, 2007). The mRNA detection method is such that the fluorescence is initially quenched by the gold nanoparticle proximity. Yet when the oligonucleotide is displaced by the specific binding of the mRNA molecules present inside the cell, the fluorescence becomes detectable and serves thus as quantitative read-out for the intracellular mRNA abundance. Exactly this is where concerns arise. To find and bind mRNA, spherical nucleic acids must leave the endosomal compartments. Is there any evidence that Nano-Flares ever achieve this and reach intact the nucleocytoplasmatic space, where their target mRNA is?

Lévy’s lab has focused its research on the commercially available analogue of the Nano-Flares, based on the patent to Mirkin and Northwestern University and sold by Merck Millipore under the trade name of SmartFlares. These were described by Mirkin as “a powerful and prolific tool in biology and medical diagnostics, with ∼ 1,600 unique forms commercially available today”. The work, led by Lévy’s postdoctoral scientist David Mason, now available in post-publication process at ScienceOpen and on Figshare, found no experimental evidence for SmartFlares to be ever found outside the endosomal membrane vesicles. On the contrary, the analysis by several complementary approaches, i.e., electron, fluorescence and photothermal microscopy, revealed that the probes are retained exclusively within the endosomal compartments.

In fact, even Merck Millipore was apparently well aware of this problem when the product was developed for the market. As I learned, Merck performed a number of assays to address the specificity issue. Multiple hundred-fold induction of mRNA by biological cell stimulation (confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR) led to no significant changes in the corresponding SmartFlare signal. Similarly, biological gene downregulation or experimental siRNA knock-down had no effect on the corresponding SmartFlare fluorescence. Cell lines confirmed as negative for a certain biomarker proved highly positive in a SmartFlare assay. Live cell imaging showed the SmartFlare signal to be almost entirely mitochondrial, inconsistent with reported patterns of the respective mRNA distributions. Elsewhere however, cyanine dye-labelled oligonucleotides were found to unspecifically localise to mitochondria (Orio et al., J. RNAi Gene Silencing 9:479-485, 2013), which might account to the often observed punctate Smart Flare signal.

…

More recently, Mirkin lab has developed a novel version of spherical nucleic acids, named Sticky-Flares (Briley et al., PNAS 112:9591-9595, 2015), which has also been patented for commercial use. The claim is that “the Sticky-flare is capable of entering live cells without the need for transfection agents and recognizing target RNA transcripts in a sequence-specific manner”. To confirm this, Lévy used the same approach as for the striped nanoparticles [not excerpted here]: he approached Mirkin by email and in person, requesting the original microscopy data from this publication. As Mirkin appeared reluctant, Lévy invoked the rules for data sharing by the journal PNAS, the funder NSF as well as the Northwestern University. After finally receiving Mirkin’s thin-optical microscopy data by air mail, Lévy and Mason re-analyzed it and determined the absence of any evidence for endosomal escape, while all Sticky-Flare particles appeared to be localized exclusively inside vesicular membrane compartments, i.e., endosomes (Mason & Levy, bioRxiv 2015).

I encourage you to read Schneider’s Nov. 20, 2015 posting in its entirety as these excerpts can’t do justice to it.

The PNAS surprise

PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Science) published one of Mirkin’s papers on ‘Sticky-flares’ and is where scientists, Raphaël Lévy and David Mason, submitted a letter outlining their concerns with the ‘Sticky-flares’ research. Here’s the response as reproduced in Lévy’s Nov. 16, 2015 posting on his Rapha-Z-Lab blog

Dear Dr. Levy,

I regret to inform you that the PNAS Editorial Board has declined to publish your Letter to the Editor. After careful consideration, the Board has decided that your letter does not contribute significantly to the discussion of this paper.

Thank you for submitting your comments to PNAS.

Sincerely yours,

Inder Verma

Editor-in-Chief

Judge for yourself, Lévy’s and Mason’s letter can be found here (pdf) and here.

Conclusions

My primary interest in this story is in the view it provides of the scientific process and the importance of and difficulty associated with the debates.

I can’t venture an opinion about the research or the counterarguments other than to say that Lévy’s and Mason’s thoughtful challenge bears more examination than PNAS is inclined to accord. If their conclusions or Chad Mirkin’s are wrong, let that be determined in an open process.

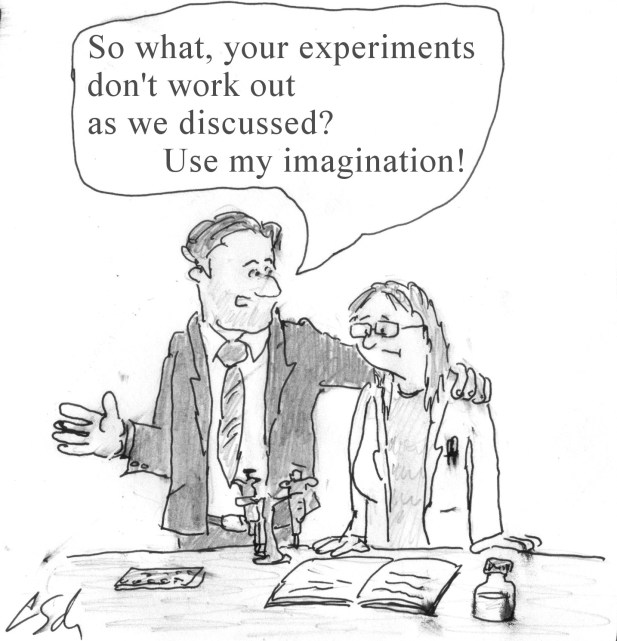

I’ll leave the very last comment to Schneider who is both writer and cartoonist, from his Nov. 20, 2015 posting,