One of the winners in Canada’s 2017 federal budget announcement of the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy was Edmonton, Alberta. It’s a fact which sometimes goes unnoticed while Canadians marvel at the wonderfulness found in Toronto and Montréal where it seems new initiatives and monies are being announced on a weekly basis (I exaggerate) for their AI (artificial intelligence) efforts.

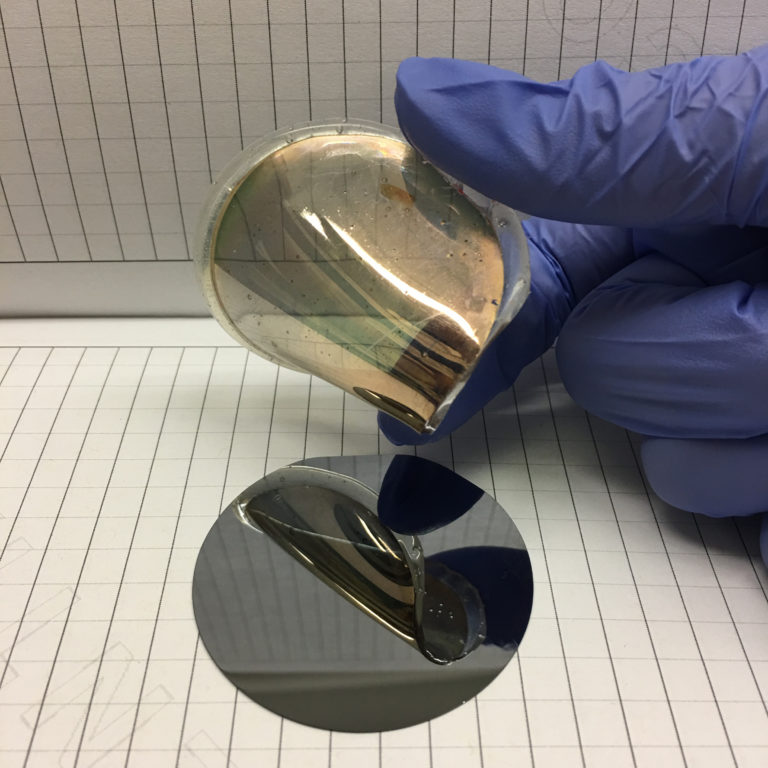

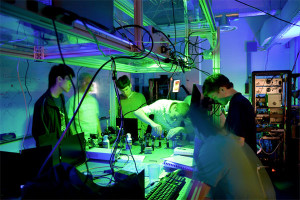

Alberta’s quantum nanotechnology hub (graduate programme)

Intriguingly, it seems that Edmonton has higher aims than (an almost unnoticed) leadership in AI. Physicists at the University of Alberta have announced hopes to be just as successful as their AI brethren in a Nov. 27, 2017 article by Juris Graney for the Edmonton Journal,

Physicists at the University of Alberta [U of A] are hoping to emulate the success of their artificial intelligence studying counterparts in establishing the city and the province as the nucleus of quantum nanotechnology research in Canada and North America.

Google’s artificial intelligence research division DeepMind announced in July [2017] it had chosen Edmonton as its first international AI research lab, based on a long-running partnership with the U of A’s 10-person AI lab.

Retaining the brightest minds in the AI and machine-learning fields while enticing a global tech leader to Alberta was heralded as a coup for the province and the university.

It is something U of A physics professor John Davis believes the university’s new graduate program, Quanta, can help achieve in the world of quantum nanotechnology.

…

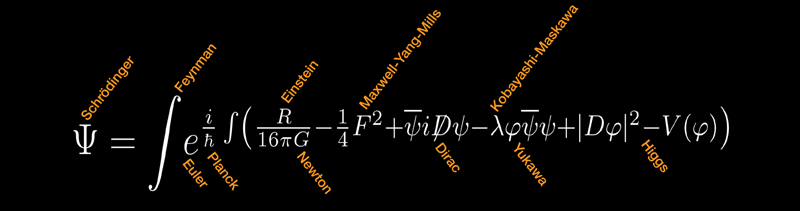

The field of quantum mechanics had long been a realm of theoretical science based on the theory that atomic and subatomic material like photons or electrons behave both as particles and waves.

“When you get right down to it, everything has both behaviours (particle and wave) and we can pick and choose certain scenarios which one of those properties we want to use,” he said.

But, Davis said, physicists and scientists are “now at the point where we understand quantum physics and are developing quantum technology to take to the marketplace.”

“Quantum computing used to be realm of science fiction, but now we’ve figured it out, it’s now a matter of engineering,” he said.

…

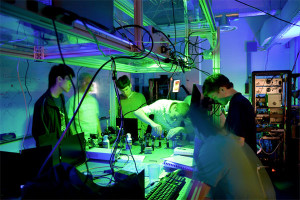

Quantum computing labs are being bought by large tech companies such as Google, IBM and Microsoft because they realize they are only a few years away from having this power, he said.

Those making the groundbreaking developments may want to commercialize their finds and take the technology to market and that is where Quanta comes in.

…

East vs. West—Again?

Ivan Semeniuk in his article, Quantum Supremacy, ignores any quantum research effort not located in either Waterloo, Ontario or metro Vancouver, British Columbia to describe a struggle between the East and the West (a standard Canadian trope). From Semeniuk’s Oct. 17, 2017 quantum article [link follows the excerpts] for the Globe and Mail’s October 2017 issue of the Report on Business (ROB),

Lazaridis [Mike], of course, has experienced lost advantage first-hand. As co-founder and former co-CEO of Research in Motion (RIM, now called Blackberry), he made the smartphone an indispensable feature of the modern world, only to watch rivals such as Apple and Samsung wrest away Blackberry’s dominance. Now, at 56, he is engaged in a high-stakes race that will determine who will lead the next technology revolution. In the rolling heartland of southwestern Ontario, he is laying the foundation for what he envisions as a new Silicon Valley—a commercial hub based on the promise of quantum technology.

Semeniuk skips over the story of how Blackberry lost its advantage. I came onto that story late in the game when Blackberry was already in serious trouble due to a failure to recognize that the field they helped to create was moving in a new direction. If memory serves, they were trying to keep their technology wholly proprietary which meant that developers couldn’t easily create apps to extend the phone’s features. Blackberry also fought a legal battle in the US with a patent troll draining company resources and energy in proved to be a futile effort.

Since then Lazaridis has invested heavily in quantum research. He gave the University of Waterloo a serious chunk of money as they named their Quantum Nano Centre (QNC) after him and his wife, Ophelia (you can read all about it in my Sept. 25, 2012 posting about the then new centre). The best details for Lazaridis’ investments in Canada’s quantum technology are to be found on the Quantum Valley Investments, About QVI, History webpage,

History has repeatedly demonstrated the power of research in physics to transform society. As a student of history and a believer in the power of physics, Mike Lazaridis set out in 2000 to make real his bold vision to establish the Region of Waterloo as a world leading centre for physics research. That is, a place where the best researchers in the world would come to do cutting-edge research and to collaborate with each other and in so doing, achieve transformative discoveries that would lead to the commercialization of breakthrough technologies.

History has repeatedly demonstrated the power of research in physics to transform society. As a student of history and a believer in the power of physics, Mike Lazaridis set out in 2000 to make real his bold vision to establish the Region of Waterloo as a world leading centre for physics research. That is, a place where the best researchers in the world would come to do cutting-edge research and to collaborate with each other and in so doing, achieve transformative discoveries that would lead to the commercialization of breakthrough technologies.

Establishing a World Class Centre in Quantum Research:

The first step in this regard was the establishment of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Perimeter was established in 2000 as an independent theoretical physics research institute. Mike started Perimeter with an initial pledge of $100 million (which at the time was approximately one third of his net worth). Since that time, Mike and his family have donated a total of more than $170 million to the Perimeter Institute. In addition to this unprecedented monetary support, Mike also devotes his time and influence to help lead and support the organization in everything from the raising of funds with government and private donors to helping to attract the top researchers from around the globe to it. Mike’s efforts helped Perimeter achieve and grow its position as one of a handful of leading centres globally for theoretical research in fundamental physics.

Perimeter is located in a Governor-General award winning designed building in Waterloo. Success in recruiting and resulting space requirements led to an expansion of the Perimeter facility. A uniquely designed addition, which has been described as space-ship-like, was opened in 2011 as the Stephen Hawking Centre in recognition of one of the most famous physicists alive today who holds the position of Distinguished Visiting Research Chair at Perimeter and is a strong friend and supporter of the organization.

Perimeter is located in a Governor-General award winning designed building in Waterloo. Success in recruiting and resulting space requirements led to an expansion of the Perimeter facility. A uniquely designed addition, which has been described as space-ship-like, was opened in 2011 as the Stephen Hawking Centre in recognition of one of the most famous physicists alive today who holds the position of Distinguished Visiting Research Chair at Perimeter and is a strong friend and supporter of the organization.

Recognizing the need for collaboration between theorists and experimentalists, in 2002, Mike applied his passion and his financial resources toward the establishment of The Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo. IQC was established as an experimental research institute focusing on quantum information. Mike established IQC with an initial donation of $33.3 million. Since that time, Mike and his family have donated a total of more than $120 million to the University of Waterloo for IQC and other related science initiatives. As in the case of the Perimeter Institute, Mike devotes considerable time and influence to help lead and support IQC in fundraising and recruiting efforts. Mike’s efforts have helped IQC become one of the top experimental physics research institutes in the world.

Mike and Doug Fregin have been close friends since grade 5. They are also co-founders of BlackBerry (formerly Research In Motion Limited). Doug shares Mike’s passion for physics and supported Mike’s efforts at the Perimeter Institute with an initial gift of $10 million. Since that time Doug has donated a total of $30 million to Perimeter Institute. Separately, Doug helped establish the Waterloo Institute for Nanotechnology at the University of Waterloo with total gifts for $29 million. As suggested by its name, WIN is devoted to research in the area of nanotechnology. It has established as an area of primary focus the intersection of nanotechnology and quantum physics.

Mike and Doug Fregin have been close friends since grade 5. They are also co-founders of BlackBerry (formerly Research In Motion Limited). Doug shares Mike’s passion for physics and supported Mike’s efforts at the Perimeter Institute with an initial gift of $10 million. Since that time Doug has donated a total of $30 million to Perimeter Institute. Separately, Doug helped establish the Waterloo Institute for Nanotechnology at the University of Waterloo with total gifts for $29 million. As suggested by its name, WIN is devoted to research in the area of nanotechnology. It has established as an area of primary focus the intersection of nanotechnology and quantum physics.

With a donation of $50 million from Mike which was matched by both the Government of Canada and the province of Ontario as well as a donation of $10 million from Doug, the University of Waterloo built the Mike & Ophelia Lazaridis Quantum-Nano Centre, a state of the art laboratory located on the main campus of the University of Waterloo that rivals the best facilities in the world. QNC was opened in September 2012 and houses researchers from both IQC and WIN.

Leading the Establishment of Commercialization Culture for Quantum Technologies in Canada:

For many years, theorists have been able to demonstrate the transformative powers of quantum mechanics on paper. That said, converting these theories to experimentally demonstrable discoveries has, putting it mildly, been a challenge. Many naysayers have suggested that achieving these discoveries was not possible and even the believers suggested that it could likely take decades to achieve these discoveries. Recently, a buzz has been developing globally as experimentalists have been able to achieve demonstrable success with respect to Quantum Information based discoveries. Local experimentalists are very much playing a leading role in this regard. It is believed by many that breakthrough discoveries that will lead to commercialization opportunities may be achieved in the next few years and certainly within the next decade.

For many years, theorists have been able to demonstrate the transformative powers of quantum mechanics on paper. That said, converting these theories to experimentally demonstrable discoveries has, putting it mildly, been a challenge. Many naysayers have suggested that achieving these discoveries was not possible and even the believers suggested that it could likely take decades to achieve these discoveries. Recently, a buzz has been developing globally as experimentalists have been able to achieve demonstrable success with respect to Quantum Information based discoveries. Local experimentalists are very much playing a leading role in this regard. It is believed by many that breakthrough discoveries that will lead to commercialization opportunities may be achieved in the next few years and certainly within the next decade.

Recognizing the unique challenges for the commercialization of quantum technologies (including risk associated with uncertainty of success, complexity of the underlying science and high capital / equipment costs) Mike and Doug have chosen to once again lead by example. The Quantum Valley Investment Fund will provide commercialization funding, expertise and support for researchers that develop breakthroughs in Quantum Information Science that can reasonably lead to new commercializable technologies and applications. Their goal in establishing this Fund is to lead in the development of a commercialization infrastructure and culture for Quantum discoveries in Canada and thereby enable such discoveries to remain here.

Semeniuk goes on to set the stage for Waterloo/Lazaridis vs. Vancouver (from Semeniuk’s 2017 ROB article),

… as happened with Blackberry, the world is once again catching up. While Canada’s funding of quantum technology ranks among the top five in the world, the European Union, China, and the US are all accelerating their investments in the field. Tech giants such as Google [also known as Alphabet], Microsoft and IBM are ramping up programs to develop companies and other technologies based on quantum principles. Meanwhile, even as Lazaridis works to establish Waterloo as the country’s quantum hub, a Vancouver-area company has emerged to challenge that claim. The two camps—one methodically focused on the long game, the other keen to stake an early commercial lead—have sparked an East-West rivalry that many observers of the Canadian quantum scene are at a loss to explain.

Is it possible that some of the rivalry might be due to an influential individual who has invested heavily in a ‘quantum valley’ and has a history of trying to ‘own’ a technology?

Getting back to D-Wave Systems, the Vancouver company, I have written about them a number of times (particularly in 2015; for the full list: input D-Wave into the blog search engine). This June 26, 2015 posting includes a reference to an article in The Economist magazine about D-Wave’s commercial opportunities while the bulk of the posting is focused on a technical breakthrough.

Semeniuk offers an overview of the D-Wave Systems story,

D-Wave was born in 1999, the same year Lazaridis began to fund quantum science in Waterloo. From the start, D-Wave had a more immediate goal: to develop a new computer technology to bring to market. “We didn’t have money or facilities,” says Geordie Rose, a physics PhD who co0founded the company and served in various executive roles. …

The group soon concluded that the kind of machine most scientists were pursing based on so-called gate-model architecture was decades away from being realized—if ever. …

Instead, D-Wave pursued another idea, based on a principle dubbed “quantum annealing.” This approach seemed more likely to produce a working system, even if the application that would run on it were more limited. “The only thing we cared about was building the machine,” says Rose. “Nobody else was trying to solve the same problem.”

D-Wave debuted its first prototype at an event in California in February 2007 running it through a few basic problems such as solving a Sudoku puzzle and finding the optimal seating plan for a wedding reception. … “They just assumed we were hucksters,” says Hilton [Jeremy Hilton, D.Wave senior vice-president of systems]. Federico Spedalieri, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California’s [USC} Information Sciences Institute who has worked with D-Wave’s system, says the limited information the company provided about the machine’s operation provoked outright hostility. “I think that played against them a lot in the following years,” he says.

It seems Lazaridis is not the only one who likes to hold company information tightly.

Back to Semeniuk and D-Wave,

Today [October 2017], the Los Alamos National Laboratory owns a D-Wave machine, which costs about $15million. Others pay to access D-Wave systems remotely. This year , for example, Volkswagen fed data from thousands of Beijing taxis into a machine located in Burnaby [one of the municipalities that make up metro Vancouver] to study ways to optimize traffic flow.

But the application for which D-Wave has the hights hope is artificial intelligence. Any AI program hings on the on the “training” through which a computer acquires automated competence, and the 2000Q [a D-Wave computer] appears well suited to this task. …

Yet, for all the buzz D-Wave has generated, with several research teams outside Canada investigating its quantum annealing approach, the company has elicited little interest from the Waterloo hub. As a result, what might seem like a natural development—the Institute for Quantum Computing acquiring access to a D-Wave machine to explore and potentially improve its value—has not occurred. …

I am particularly interested in this comment as it concerns public funding (from Semeniuk’s article),

Vern Brownell, a former Goldman Sachs executive who became CEO of D-Wave in 2009, calls the lack of collaboration with Waterloo’s research community “ridiculous,” adding that his company’s efforts to establish closer ties have proven futile, “I’ll be blunt: I don’t think our relationship is good enough,” he says. Brownell also point out that, while hundreds of millions in public funds have flowed into Waterloo’s ecosystem, little funding is available for Canadian scientists wishing to make the most of D-Wave’s hardware—despite the fact that it remains unclear which core quantum technology will prove the most profitable.

There’s a lot more to Semeniuk’s article but this is the last excerpt,

The world isn’t waiting for Canada’s quantum rivals to forge a united front. Google, Microsoft, IBM, and Intel are racing to develop a gate-model quantum computer—the sector’s ultimate goal. (Google’s researchers have said they will unveil a significant development early next year.) With the U.K., Australia and Japan pouring money into quantum, Canada, an early leader, is under pressure to keep up. The federal government is currently developing a strategy for supporting the country’s evolving quantum sector and, ultimately, getting a return on its approximately $1-billion investment over the past decade [emphasis mine].

I wonder where the “approximately $1-billion … ” figure came from. I ask because some years ago MP Peter Julian asked the government for information about how much Canadian federal money had been invested in nanotechnology. The government replied with sheets of paper (a pile approximately 2 inches high) that had funding disbursements from various ministries. Each ministry had its own method with different categories for listing disbursements and the titles for the research projects were not necessarily informative for anyone outside a narrow specialty. (Peter Julian’s assistant had kindly sent me a copy of the response they had received.) The bottom line is that it would have been close to impossible to determine the amount of federal funding devoted to nanotechnology using that data. So, where did the $1-billion figure come from?

In any event, it will be interesting to see how the Council of Canadian Academies assesses the ‘quantum’ situation in its more academically inclined, “The State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada,” when it’s released later this year (2018).

Finally, you can find Semeniuk’s October 2017 article here but be aware it’s behind a paywall.

Whither we goest?

Despite any doubts one might have about Lazaridis’ approach to research and technology, his tremendous investment and support cannot be denied. Without him, Canada’s quantum research efforts would be substantially less significant. As for the ‘cowboys’ in Vancouver, it takes a certain temperament to found a start-up company and it seems the D-Wave folks have more in common with Lazaridis than they might like to admit. As for the Quanta graduate programme, it’s early days yet and no one should ever count out Alberta.

Meanwhile, one can continue to hope that a more thoughtful approach to regional collaboration will be adopted so Canada can continue to blaze trails in the field of quantum research.

History has repeatedly demonstrated the power of research in physics to transform society. As a student of history and a believer in the power of physics, Mike Lazaridis set out in 2000 to make real his bold vision to establish the Region of Waterloo as a world leading centre for physics research. That is, a place where the best researchers in the world would come to do cutting-edge research and to collaborate with each other and in so doing, achieve transformative discoveries that would lead to the commercialization of breakthrough technologies.

History has repeatedly demonstrated the power of research in physics to transform society. As a student of history and a believer in the power of physics, Mike Lazaridis set out in 2000 to make real his bold vision to establish the Region of Waterloo as a world leading centre for physics research. That is, a place where the best researchers in the world would come to do cutting-edge research and to collaborate with each other and in so doing, achieve transformative discoveries that would lead to the commercialization of breakthrough technologies. Perimeter is located in a Governor-General award winning designed building in Waterloo. Success in recruiting and resulting space requirements led to an expansion of the Perimeter facility. A uniquely designed addition, which has been described as space-ship-like, was opened in 2011 as the

Perimeter is located in a Governor-General award winning designed building in Waterloo. Success in recruiting and resulting space requirements led to an expansion of the Perimeter facility. A uniquely designed addition, which has been described as space-ship-like, was opened in 2011 as the  Mike and Doug Fregin have been close friends since grade 5. They are also co-founders of BlackBerry (formerly Research In Motion Limited). Doug shares Mike’s passion for physics and supported Mike’s efforts at the Perimeter Institute with an initial gift of $10 million. Since that time Doug has donated a total of $30 million to Perimeter Institute. Separately, Doug helped establish the

Mike and Doug Fregin have been close friends since grade 5. They are also co-founders of BlackBerry (formerly Research In Motion Limited). Doug shares Mike’s passion for physics and supported Mike’s efforts at the Perimeter Institute with an initial gift of $10 million. Since that time Doug has donated a total of $30 million to Perimeter Institute. Separately, Doug helped establish the  For many years, theorists have been able to demonstrate the transformative powers of quantum mechanics on paper. That said, converting these theories to experimentally demonstrable discoveries has, putting it mildly, been a challenge. Many naysayers have suggested that achieving these discoveries was not possible and even the believers suggested that it could likely take decades to achieve these discoveries. Recently, a buzz has been developing globally as experimentalists have been able to achieve demonstrable success with respect to Quantum Information based discoveries. Local experimentalists are very much playing a leading role in this regard. It is believed by many that breakthrough discoveries that will lead to commercialization opportunities may be achieved in the next few years and certainly within the next decade.

For many years, theorists have been able to demonstrate the transformative powers of quantum mechanics on paper. That said, converting these theories to experimentally demonstrable discoveries has, putting it mildly, been a challenge. Many naysayers have suggested that achieving these discoveries was not possible and even the believers suggested that it could likely take decades to achieve these discoveries. Recently, a buzz has been developing globally as experimentalists have been able to achieve demonstrable success with respect to Quantum Information based discoveries. Local experimentalists are very much playing a leading role in this regard. It is believed by many that breakthrough discoveries that will lead to commercialization opportunities may be achieved in the next few years and certainly within the next decade.