A July 25, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily describes research utilizing dead spiders,

Spiders are amazing. They’re useful even when they’re dead.

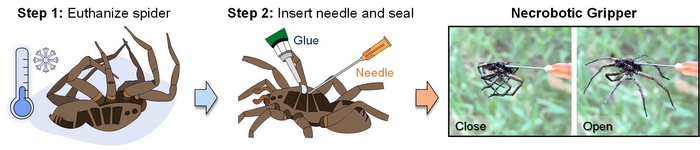

Rice University mechanical engineers are showing how to repurpose deceased spiders as mechanical grippers that can blend into natural environments while picking up objects, like other insects, that outweigh them.

…

A July 25, 2022 Rice University news release (also on on EurekAlert but published August 4, 2022), which originated the news item, explains the reasoning, Note: Links have been removed,

“It happens to be the case that the spider, after it’s deceased, is the perfect architecture for small scale, naturally derived grippers,” said Daniel Preston of Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering.

An open-access study in Advanced Science outlines the process by which Preston and lead author Faye Yap harnessed a spider’s physiology in a first step toward a novel area of research they call “necrobotics.”

Preston’s lab specializes in soft robotic systems that often use nontraditional materials, as opposed to hard plastics, metals and electronics. “We use all kinds of interesting new materials like hydrogels and elastomers that can be actuated by things like chemical reactions, pneumatics and light,” he said. “We even have some recent work on textiles and wearables.

“This area of soft robotics is a lot of fun because we get to use previously untapped types of actuation and materials,” Preston said. “The spider falls into this line of inquiry. It’s something that hasn’t been used before but has a lot of potential.”

Unlike people and other mammals that move their limbs by synchronizing opposing muscles, spiders use hydraulics. A chamber near their heads contracts to send blood to limbs, forcing them to extend. When the pressure is relieved, the legs contract.

The cadavers Preston’s lab pressed into service were wolf spiders, and testing showed they were reliably able to lift more than 130% of their own body weight, and sometimes much more. They had the grippers manipulate a circuit board, move objects and even lift another spider.

The researchers noted smaller spiders can carry heavier loads in comparison to their size. Conversely, the larger the spider, the smaller the load it can carry in comparison to its own body weight. Future research will likely involve testing this concept with spiders smaller than the wolf spider, Preston said

Yap said the project began shortly after Preston established his lab in Rice’s Department of Mechanical Engineering in 2019.

“We were moving stuff around in the lab and we noticed a curled up spider at the edge of the hallway,” she said. “We were really curious as to why spiders curl up after they die.”

A quick search found the answer: “Spiders do not have antagonistic muscle pairs, like biceps and triceps in humans,” Yap said. “They only have flexor muscles, which allow their legs to curl in, and they extend them outward by hydraulic pressure. When they die, they lose the ability to actively pressurize their bodies. That’s why they curl up.

“At the time, we were thinking, ‘Oh, this is super interesting.’ We wanted to find a way to leverage this mechanism,” she said.

Internal valves in the spiders’ hydraulic chamber, or prosoma, allow them to control each leg individually, and that will also be the subject of future research, Preston said. “The dead spider isn’t controlling these valves,” he said. “They’re all open. That worked out in our favor in this study, because it allowed us to control all the legs at the same time.”

Setting up a spider gripper was fairly simple. Yap tapped into the prosoma chamber with a needle, attaching it with a dab of superglue. The other end of the needle was connected to one of the lab’s test rigs or a handheld syringe, which delivered a minute amount of air to activate the legs almost instantly.

The lab ran one ex-spider through 1,000 open-close cycles to see how well its limbs held up, and found it to be fairly robust. “It starts to experience some wear and tear as we get close to 1,000 cycles,” Preston said. “We think that’s related to issues with dehydration of the joints. We think we can overcome that by applying polymeric coatings.”

What turns the lab’s work from a cool stunt into a useful technology?

Preston said a few necrobotic applications have occurred to him. “There are a lot of pick-and-place tasks we could look into, repetitive tasks like sorting or moving objects around at these small scales, and maybe even things like assembly of microelectronics,” he said.

“Another application could be deploying it to capture smaller insects in nature, because it’s inherently camouflaged,” Yap added.

“Also, the spiders themselves are biodegradable,” Preston said. “So we’re not introducing a big waste stream, which can be a problem with more traditional components.”

Preston and Yap are aware the experiments may sound to some people like the stuff of nightmares, but they said what they’re doing doesn’t qualify as reanimation.

“Despite looking like it might have come back to life, we’re certain that it’s inanimate, and we’re using it in this case strictly as a material derived from a once-living spider,” Preston said. “It’s providing us with something really useful.”

Co-authors of the paper are graduate students Zhen Liu and Trevor Shimokusu and postdoctoral fellow Anoop Rajappan. Preston is an assistant professor of mechanical engineering.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Necrobotics: Biotic Materials as Ready-to-Use Actuators by Te Faye Yap, Zhen Liu, Anoop Rajappan, Trevor J. Shimokusu, Daniel J. Preston. Advanced Science

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202201174 First published: 25 July 2022

As noted in the news release, this paper is open access.