Specifically, the researchers are describing these as cellulose nanofibrils. On the left of the image, the seed look mores like an egg waiting to be fried for breakfast but the image on the right is definitely fibrous-looking,

A December 18, 2018 news item on Nanowerk describes the research into seeds and cellulose,

The seeds of some plants such as basil, watercress or plantain form a mucous envelope as soon as they come into contact with water. This cover consists of cellulose in particular, which is an important structural component of the primary cell wall of green plants, and swelling pectins, plant polysaccharides.

In order to be able to investigate its physical properties, a research team from the Zoological Institute at Kiel University (CAU) used a special drying method, which gently removes the water from the cellulosic mucous sheath. The team discovered that this method can produce extremely strong nanofibres from natural cellulose. In future, they could be especially interesting for applications in biomedicine.

A December 18, 2018 Kiel University press release, which originated the news item, offers further details about the work,

Thanks to their slippery mucous sheath, seeds can slide through the digestive tract of birds undigested. They are excreted unharmed, and can be dispersed in this way. It is presumed that the mucous layer provides protection. “In order to find out more about the function of the mucilage, we first wanted to study the structure and the physical properties of this seed envelope material,” said Zoology Professor Stanislav N. Gorb, head of the “Functional Morphology and Biomechanics” working group at the CAU. In doing so they discovered that its properties depend on the alignment of the fibres that anchor them to the seed surface

Diverse properties: From slippery to sticky

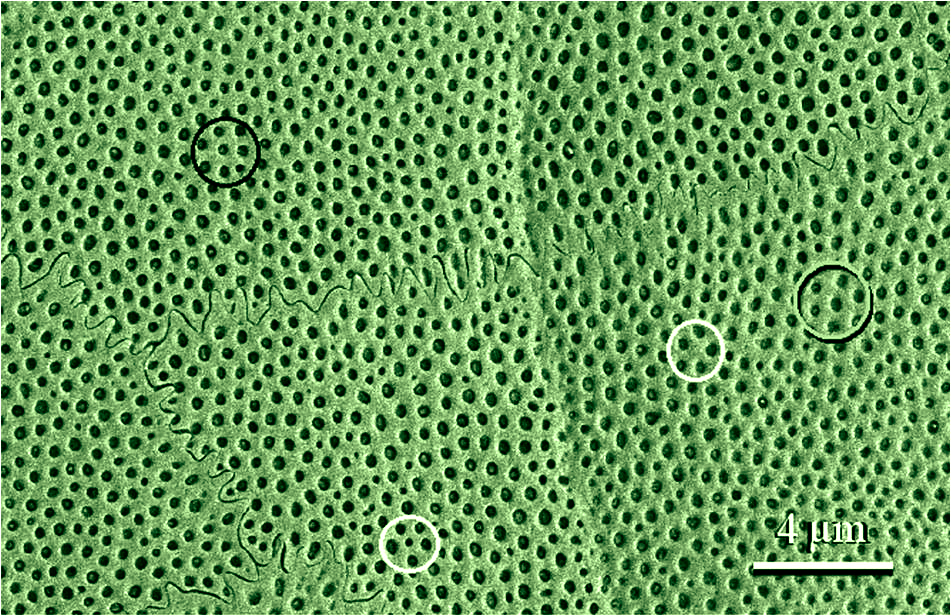

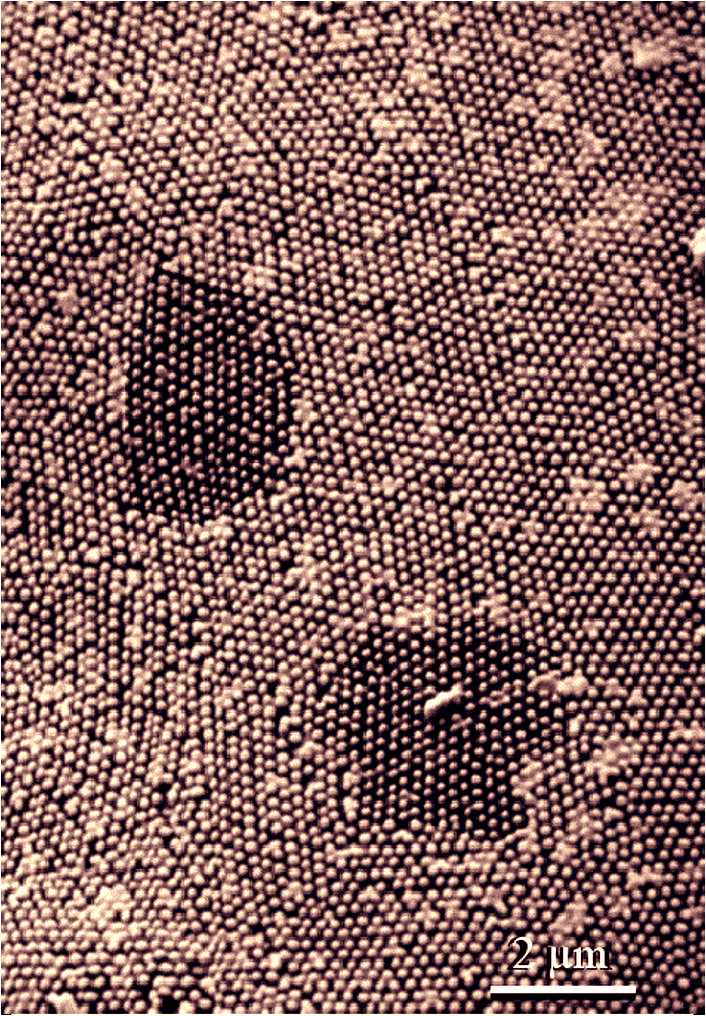

The pectins in the shell of the seeds can absorb a large quantity of water, and thus form a gel-like capsule around the seed in a few minutes. It is anchored firmly to the surface of the seed by fine cellulose fibres with a diameter of just up to 100 nanometres, similar to the microscopic adhesive elements on the surface of highly-adhesive gecko feet. So in a sense, the fibres form the stabilising backbone of the mucous sheath.

The properties of the mucous change, depending on the water concentration. “The mucous actually makes the seeds very slippery. However, if we reduce the water content, it becomes sticky and begins to stick,” said Stanislav Gorb, summarising a result from previous studies together with Dr Agnieszka Kreitschitz. The adhesive strength is also increased by the forces acting between the individual vertically-arranged nanofibres of the seed and the adhesive surface.

Specially dried

In order to be able to investigate the mucous sheath under a scanning electron microscope, the Kiel research team used a particularly gentle method, so-called critical-point drying (CPD). They dehydrated the mucous sheath of various seeds step-by-step with liquid carbon dioxide – instead of the normal method using ethanol. The advantage of this method is that evaporation of liquid carbon dioxide can be controlled under certain pressure and temperature conditions, without surface tension developing within the sheath. As a result, the research team was able to precisely remove water from the mucous, without drying out the surface of the sheath and thereby destroying the original cell structure. Through the highly-precise drying, the structural arrangement of the individual cellulose fibres remained intact.

Almost as strongly-adhesive as carbon nanotubes

The research team tested the dried cellulose fibres regarding their friction and adhesion properties, and compared them with those of synthetically-produced carbon nanotubes. Due to their outstanding properties, such as their tensile strength, electrical conductivity or their friction, these microscopic structures are interesting for numerous industrial applications of the future.

“Our tests showed that the frictional and adhesive forces of the cellulose fibres are almost as strong as with vertically-arranged carbon nanotubes,” said Dr Clemens Schaber, first author of the study. The structural dimensions of the cellulose nanofibers are similar to the vertically aligned carbon nanotubes. Through the special drying method, they can also vary the adhesive strength in a targeted manner. In Gorb’s working group, the zoologist and biomechanic examines the functioning of biological nanofibres, and the potential to imitate them with technical means. “As a natural raw material, cellulose fibres have distinct advantages over carbon nanotubes, whose health effects have not yet been fully investigated,” continued Schaber. Nanocellulose is primarily found in biodegradable polymer composites, which are used in biomedicine, cosmetics or the food industry.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Friction-Active Surfaces Based on Free-Standing Anchored Cellulose Nanofibrils by Clemens F. Schaber, Agnieszka Kreitschitz, and Stanislav N. Gorb. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10 (43), pp 37566–37574 DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b05972 Publication Date (Web): September 19, 2018

Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.