A September 1, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily announces a new type of memristor from Texas A&M University (Texas A&M or TAMU) and the National University of Singapore (NUS)

In a discovery published in the journal Nature, an international team of researchers has described a novel molecular device with exceptional computing prowess.

Reminiscent of the plasticity of connections in the human brain, the device can be reconfigured on the fly for different computational tasks by simply changing applied voltages. Furthermore, like nerve cells can store memories, the same device can also retain information for future retrieval and processing.

…

Two of the universities involved in the research have issued news/press releases. I’m going to start with the September 1, 2021 Texas A&M University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item on ScienceDaily,

“The brain has the remarkable ability to change its wiring around by making and breaking connections between nerve cells. Achieving something comparable in a physical system has been extremely challenging,” said Dr. R. Stanley Williams [emphasis mine], professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Texas A&M University. “We have now created a molecular device with dramatic reconfigurability, which is achieved not by changing physical connections like in the brain, but by reprogramming its logic.”

Dr. T. Venkatesan, director of the Center for Quantum Research and Technology (CQRT) at the University of Oklahoma, Scientific Affiliate at National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, and adjunct professor of electrical and computer engineering at the National University of Singapore, added that their molecular device might in the future help design next-generation processing chips with enhanced computational power and speed, but consuming significantly reduced energy.

Whether it is the familiar laptop or a sophisticated supercomputer, digital technologies face a common nemesis, the von Neumann bottleneck. This delay in computational processing is a consequence of current computer architectures, wherein the memory, containing data and programs, is physically separated from the processor. As a result, computers spend a significant amount of time shuttling information between the two systems, causing the bottleneck. Also, despite extremely fast processor speeds, these units can be idling for extended amounts of time during periods of information exchange.

As an alternative to conventional electronic parts used for designing memory units and processors, devices called memristors offer a way to circumvent the von Neumann bottleneck. Memristors, such as those made of niobium dioxide and vanadium dioxide, transition from being an insulator to a conductor at a set temperature. This property gives these types of memristors the ability to perform computations and store data.

However, despite their many advantages, these metal oxide memristors are made of rare-earth elements and can operate only in restrictive temperature regimes. Hence, there has been an ongoing search for promising organic molecules that can perform a comparable memristive function, said Williams.

Dr. Sreebrata Goswami, a professor at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, designed the material used in this work. The compound has a central metal atom (iron) bound to three phenyl azo pyridine organic molecules called ligands.

“This behaves like an electron sponge that can absorb as many as six electrons reversibly, resulting in seven different redox states,” said Sreebrata. “The interconnectivity between these states is the key behind the reconfigurability shown in this work.”

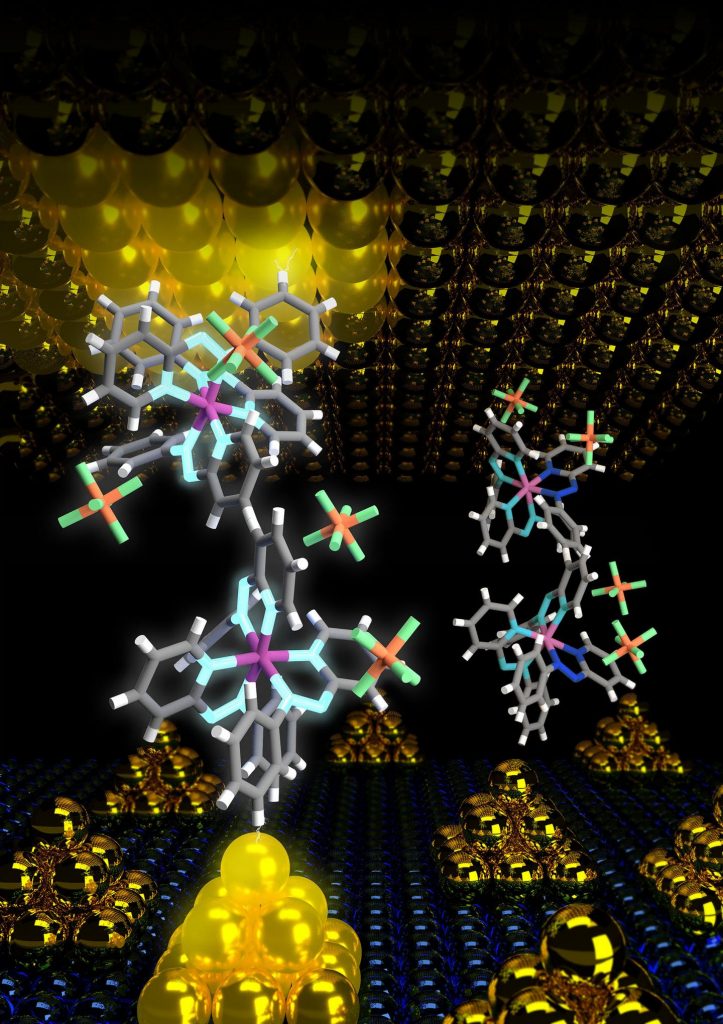

Dr. Sreetosh Goswami, a researcher at the National University of Singapore, devised this project by creating a tiny electrical circuit consisting of a 40-nanometer layer of molecular film sandwiched between a layer of gold on top and gold-infused nanodisc and indium tin oxide at the bottom.

On applying a negative voltage on the device, Sreetosh witnessed a current-voltage profile that was nothing like anyone had seen before. Unlike metal-oxide memristors that can switch from metal to insulator at only one fixed voltage, the organic molecular devices could switch back and forth from insulator to conductor at several discrete sequential voltages.

“So, if you think of the device as an on-off switch, as we were sweeping the voltage more negative, the device first switched from on to off, then off to on, then on to off and then back to on. I’ll say that we were just blown out of our seat,” said Venkatesan. “We had to convince ourselves that what we were seeing was real.”

Sreetosh and Sreebrata investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the curious switching behavior using an imaging technique called Raman spectroscopy. In particular, they looked for spectral signatures in the vibrational motion of the organic molecule that could explain the multiple transitions. Their investigation revealed that sweeping the voltage negative triggered the ligands on the molecule to undergo a series of reduction, or electron-gaining, events that caused the molecule to transition between off state and on states.

Next, to describe the extremely complex current-voltage profile of the molecular device mathematically, Williams deviated from the conventional approach of basic physics-based equations. Instead, he described the behavior of the molecules using a decision tree algorithm with “if-then-else” statements, a commonplace line of code in several computer programs, particularly digital games.

“Video games have a structure where you have a character that does something, and then something occurs as a result. And so, if you write that out in a computer algorithm, they are if-then-else statements,” said Williams. “Here, the molecule is switching from on to off as a consequence of applied voltage, and that’s when I had the eureka moment to use decision trees to describe these devices, and it worked very well.”

But the researchers went a step further to exploit these molecular devices to run programs for different real-world computational tasks. Sreetosh showed experimentally that their devices could perform fairly complex computations in a single time step and then be reprogrammed to perform another task in the next instant.

“It was quite extraordinary; our device was doing something like what the brain does, but in a very different way,” said Sreetosh. “When you’re learning something new or when you’re deciding, the brain can actually reconfigure and change physical wiring around. Similarly, we can logically reprogram or reconfigure our devices by giving them a different voltage pulse then they’ve seen before.”

Venkatesan noted that it would take thousands of transistors to perform the same computational functions as one of their molecular devices with its different decision trees. Hence, he said their technology might first be used in handheld devices, like cell phones and sensors, and other applications where power is limited.

Other contributors to the research include Dr. Abhijeet Patra and Dr. Ariando from the National University of Singapore; Dr. Rajib Pramanick and Dr. Santi Prasad Rath from the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science; Dr. Martin Foltin from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Colorado; and Dr. Damien Thompson from the University of Limerick, Ireland.

Venkatesan said that this research is indicative of the future discoveries from this collaborative team, which will include the center of nanoscience and engineering at the Indian Institute of Science and the Microsystems and Nanotechnology Division at the NIST.

I’ve highlighted R. Stanley Williams because he and his team at HP [Hewlett Packard] Labs helped to kick off current memristor research in 2008 with the publication of two papers as per my April 5, 2010 posting,

In 2008, two memristor papers were published in Nature and Nature Nanotechnology, respectively. In the first (Nature, May 2008 [article still behind a paywall], a team at HP Labs claimed they had proved the existence of memristors (a fourth member of electrical engineering’s ‘Holy Trinity of the capacitor, resistor, and inductor’). In the second paper (Nature Nanotechnology, July 2008 [article still behind a paywall]) the team reported that they had achieved engineering control.

…

There is more technical detail in the September 2, 2022 NUS press release (also on EurekAlert),

Many electronic devices today are dependent on semiconductor logic circuits based on switches hard-wired to perform predefined logic functions. Physicists from the National University of Singapore (NUS), together with an international team of researchers, have developed a novel molecular memristor, or an electronic memory device, that has exceptional memory reconfigurability.

Unlike hard-wired standard circuits, the molecular device can be reconfigured using voltage to embed different computational tasks. The energy-efficient new technology, which is capable of enhanced computational power and speed, can potentially be used in edge computing, as well as handheld devices and applications with limited power resource.

“This work is a significant breakthrough in our quest to design low-energy computing. The idea of using multiple switching in a single element draws inspiration from how the brain works and fundamentally reimagines the design strategy of a logic circuit,” said Associate Professor Ariando from the NUS Department of Physics who led the research.

The research was first published in the journal Nature on 1 September 2021, and carried out in collaboration with the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, the University of Limerick, the University of Oklahoma, and Texas A&M University.

Brain-inspired technology

“This new discovery can contribute to developments in edge computing as a sophisticated in-memory computing approach to overcome the von Neumann bottleneck, a delay in computational processing seen in many digital technologies due to the physical separation of memory storage from a device’s processor,” said Assoc Prof Ariando. The new molecular device also has the potential to contribute to designing next generation processing chips with enhanced computational power and speed.

“Similar to the flexibility and adaptability of connections in the human brain, our memory device can be reconfigured on the fly for different computational tasks by simply changing applied voltages. Furthermore, like how nerve cells can store memories, the same device can also retain information for future retrieval and processing,” said first author Dr Sreetosh Goswami, Research Fellow from the Department of Physics at NUS.

Research team member Dr Sreebrata Goswami, who was a Senior Research Scientist at NUS and previously Professor at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, conceptualised and designed a molecular system belonging to the chemical family of phenyl azo pyridines that have a central metal atom bound to organic molecules called ligands. “These molecules are like electron sponges that can offer as many as six electron transfers resulting in five different molecular states. The interconnectivity between these states is the key behind the device’s reconfigurability,” explained Dr Sreebrata Goswami.

Dr Sreetosh Goswami created a tiny electrical circuit consisting a 40-nanometer layer of molecular film sandwiched between a top layer of gold, and a bottom layer of gold-infused nanodisc and indium tin oxide. He observed an unprecedented current-voltage profile upon applying a negative voltage to the device. Unlike conventional metal-oxide memristors that are switched on and off at only one fixed voltage, these organic molecular devices could switch between on-off states at several discrete sequential voltages.

Using an imaging technique called Raman spectroscopy, spectral signatures in the vibrational motion of the organic molecule were observed to explain the multiple transitions. Dr Sreebrata Goswami explained, “Sweeping the negative voltage triggered the ligands on the molecule to undergo a series of reduction, or electron-gaining which caused the molecule to transition between off and on states.”

The researchers described the behavior of the molecules using a decision tree algorithm with “if-then-else” statements, which is used in the coding of several computer programs, particularly digital games, as compared to the conventional approach of using basic physics-based equations.

New possibilities for energy-efficient devices

Building on their research, the team used the molecular memory devices to run programs for different real-world computational tasks. As a proof of concept, the team demonstrated that their technology could perform complex computations in a single step, and could be reprogrammed to perform another task in the next instant. An individual molecular memory device could perform the same computational functions as thousands of transistors, making the technology a more powerful and energy-efficient memory option.

“The technology might first be used in handheld devices, like cell phones and sensors, and other applications where power is limited,” added Assoc Prof Ariando.

The team in the midst of building new electronic devices incorporating their innovation, and working with collaborators to conduct simulation and benchmarking relating to existing technologies.

Other contributors to the research paper include Abhijeet Patra and Santi Prasad Rath from NUS, Rajib Pramanick from the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Martin Foltin from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Damien Thompson from the University of Limerick, T. Venkatesan from the University of Oklahoma, and R. Stanley Williams from Texas A&M University.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Decision trees within a molecular memristor by Sreetosh Goswami, Rajib Pramanick, Abhijeet Patra, Santi Prasad Rath, Martin Foltin, A. Ariando, Damien Thompson, T. Venkatesan, Sreebrata Goswami & R. Stanley Williams. Nature volume 597, pages 51–56 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03748-0 Published 01 September 2021 Issue Date 02 September 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.