Given my recent spate of posts about computing and the future of the chip (list to follow at the end of this post), this Rice University [Texas, US] research suggests that some improvements to current memory devices might be coming to the market in the near future. From a July 12, 2014 news item on Azonano,

Rice University’s breakthrough silicon oxide technology for high-density, next-generation computer memory is one step closer to mass production, thanks to a refinement that will allow manufacturers to fabricate devices at room temperature with conventional production methods.

A July 10, 2014 Rice University news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

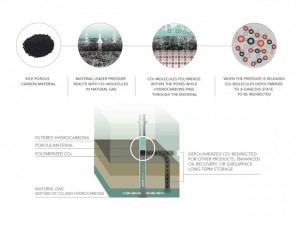

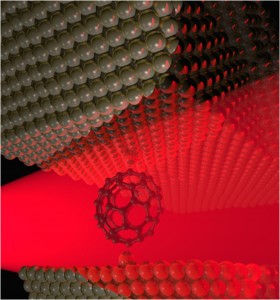

Tour and colleagues began work on their breakthrough RRAM technology more than five years ago. The basic concept behind resistive memory devices is the insertion of a dielectric material — one that won’t normally conduct electricity — between two wires. When a sufficiently high voltage is applied across the wires, a narrow conduction path can be formed through the dielectric material.

The presence or absence of these conduction pathways can be used to represent the binary 1s and 0s of digital data. Research with a number of dielectric materials over the past decade has shown that such conduction pathways can be formed, broken and reformed thousands of times, which means RRAM can be used as the basis of rewritable random-access memory.

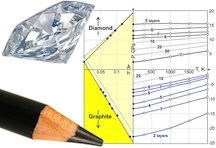

RRAM is under development worldwide and expected to supplant flash memory technology in the marketplace within a few years because it is faster than flash and can pack far more information into less space. For example, manufacturers have announced plans for RRAM prototype chips that will be capable of storing about one terabyte of data on a device the size of a postage stamp — more than 50 times the data density of current flash memory technology.

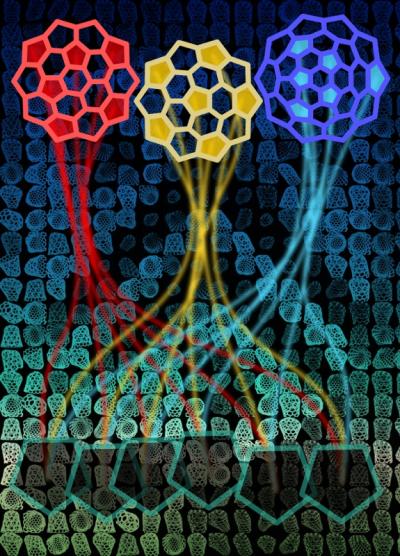

The key ingredient of Rice’s RRAM is its dielectric component, silicon oxide. Silicon is the most abundant element on Earth and the basic ingredient in conventional microchips. Microelectronics fabrication technologies based on silicon are widespread and easily understood, but until the 2010 discovery of conductive filament pathways in silicon oxide in Tour’s lab, the material wasn’t considered an option for RRAM.

Since then, Tour’s team has raced to further develop its RRAM and even used it for exotic new devices like transparent flexible memory chips. At the same time, the researchers also conducted countless tests to compare the performance of silicon oxide memories with competing dielectric RRAM technologies.

“Our technology is the only one that satisfies every market requirement, both from a production and a performance standpoint, for nonvolatile memory,” Tour said. “It can be manufactured at room temperature, has an extremely low forming voltage, high on-off ratio, low power consumption, nine-bit capacity per cell, exceptional switching speeds and excellent cycling endurance.”

In the latest study, a team headed by lead author and Rice postdoctoral researcher Gunuk Wang showed that using a porous version of silicon oxide could dramatically improve Rice’s RRAM in several ways. First, the porous material reduced the forming voltage — the power needed to form conduction pathways — to less than two volts, a 13-fold improvement over the team’s previous best and a number that stacks up against competing RRAM technologies. In addition, the porous silicon oxide also allowed Tour’s team to eliminate the need for a “device edge structure.”

“That means we can take a sheet of porous silicon oxide and just drop down electrodes without having to fabricate edges,” Tour said. “When we made our initial announcement about silicon oxide in 2010, one of the first questions I got from industry was whether we could do this without fabricating edges. At the time we could not, but the change to porous silicon oxide finally allows us to do that.”

Wang said, “We also demonstrated that the porous silicon oxide material increased the endurance cycles more than 100 times as compared with previous nonporous silicon oxide memories. Finally, the porous silicon oxide material has a capacity of up to nine bits per cell that is highest number among oxide-based memories, and the multiple capacity is unaffected by high temperatures.”

Tour said the latest developments with porous silicon oxide — reduced forming voltage, elimination of need for edge fabrication, excellent endurance cycling and multi-bit capacity — are extremely appealing to memory companies.

“This is a major accomplishment, and we’ve already been approached by companies interested in licensing this new technology,” he said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanoporous Silicon Oxide Memory by Gunuk Wang, Yang Yang, Jae-Hwang Lee, Vera Abramova, Huilong Fei, Gedeng Ruan, Edwin L. Thomas, and James M. Tour. Nano Lett., Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/nl501803s Publication Date (Web): July 3, 2014

Copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

As for my recent spate of posts on computers and chips, there’s a July 11, 2014 posting about IBM, a 7nm chip, and much more; a July 9, 2014 posting about Intel and its 14nm low-power chip processing and plans for a 10nm chip; and, finally, a June 26, 2014 posting about HP Labs and its plans for memristive-based computing and their project dubbed ‘The Machine’.