I went down a rabbit hole while trying to figure out the difference between ‘organic’ memristors and standard memristors. I have put the results of my investigation at the end of this post. First, there’s the news.

An April 21, 2020 news item on ScienceDaily explains why researchers are so focused on memristors and brainlike computing,

The advent of artificial intelligence, machine learning and the internet of things is expected to change modern electronics and bring forth the fourth Industrial Revolution. The pressing question for many researchers is how to handle this technological revolution.

“It is important for us to understand that the computing platforms of today will not be able to sustain at-scale implementations of AI algorithms on massive datasets,” said Thirumalai Venkatesan, one of the authors of a paper published in Applied Physics Reviews, from AIP Publishing.

“Today’s computing is way too energy-intensive to handle big data. We need to rethink our approaches to computation on all levels: materials, devices and architecture that can enable ultralow energy computing.”

…

An April 21, 2020 American Institute of Physics (AIP) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the authors’ approach to the problems with organic memristors,

Brain-inspired electronics with organic memristors could offer a functionally promising and cost- effective platform, according to Venkatesan. Memristive devices are electronic devices with an inherent memory that are capable of both storing data and performing computation. Since memristors are functionally analogous to the operation of neurons, the computing units in the brain, they are optimal candidates for brain-inspired computing platforms.

Until now, oxides have been the leading candidate as the optimum material for memristors. Different material systems have been proposed but none have been successful so far.

“Over the last 20 years, there have been several attempts to come up with organic memristors, but none of those have shown any promise,” said Sreetosh Goswami, lead author on the paper. “The primary reason behind this failure is their lack of stability, reproducibility and ambiguity in mechanistic understanding. At a device level, we are now able to solve most of these problems,”

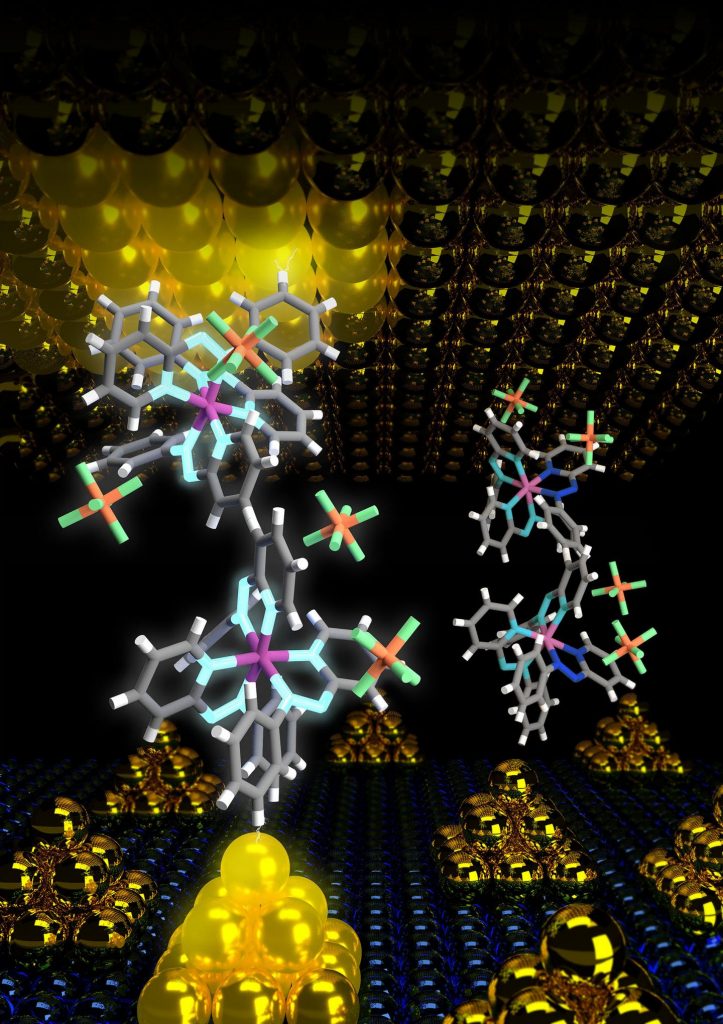

This new generation of organic memristors is developed based on metal azo complex devices, which are the brainchild of Sreebata Goswami, a professor at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in Kolkata and another author on the paper.

“In thin films, the molecules are so robust and stable that these devices can eventually be the right choice for many wearable and implantable technologies or a body net, because these could be bendable and stretchable,” said Sreebata Goswami. A body net is a series of wireless sensors that stick to the skin and track health.

The next challenge will be to produce these organic memristors at scale, said Venkatesan.

“Now we are making individual devices in the laboratory. We need to make circuits for large-scale functional implementation of these devices.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

An organic approach to low energy memory and brain inspired electronics by Sreetosh Goswami, Sreebrata Goswami, and T. Venkatesan. Applied Physics Reviews 7, 021303 (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5124155

This paper is open access.

Basics about memristors and organic memristors

This undated article on Nanowerk provides a relatively complete and technical description of memristors in general (Note: A link has been removed),

A memristor (named as a portmanteau of memory and resistor) is a non-volatile electronic memory device that was first theorized by Leon Ong Chua in 1971 as the fourth fundamental two-terminal circuit element following the resistor, the capacitor, and the inductor (IEEE Transactions on Circuit Theory, “Memristor-The missing circuit element”).

Its special property is that its resistance can be programmed (resistor function) and subsequently remains stored (memory function). Unlike other memories that exist today in modern electronics, memristors are stable and remember their state even if the device loses power.

However, it was only almost 40 years later that the first practical device was fabricated. This was in 2008, when a group led by Stanley Williams at HP Research Labs realized that switching of the resistance between a conducting and less conducting state in metal-oxide thin-film devices was showing Leon Chua’s memristor behavior. …

The article on Nanowerk includes an embedded video presentation on memristors given by Stanley Williams (also known as R. Stanley Williams).

Mention of an ‘organic’memristor can be found in an October 31, 2017 article by Ryan Whitwam,

…

The memristor is composed of the transition metal ruthenium complexed with “azo-aromatic ligands.” [emphasis mine] The theoretical work enabling this material was performed at Yale, and the organic molecules were synthesized at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Sciences. …

I highlighted ‘ligands’ because that appears to be the difference. However, there is more than one type of ligand on Wikipedia.

First, there’s the Ligand (biochemistry) entry (Note: Links have been removed),

In biochemistry and pharmacology, a ligand is a substance that forms a complex with a biomolecule to serve a biological purpose. …

Then, there’s the Ligand entry,

In coordination chemistry, a ligand[help 1] is an ion or molecule (functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex …

Finally, there’s the Ligand (disambiguation) entry (Note: Links have been removed),

- Ligand, an atom, ion, or functional group that donates one or more of its electrons through a coordinate covalent bond to one or more central atoms or ions

- Ligand (biochemistry), a substance that binds to a protein

- a ‘guest’ in host–guest chemistry

I did take a look at the paper and did not see any references to proteins or other biomolecules that I could recognize as such. I’m not sure why the researchers are describing their device as an ‘organic’ memristor but this may reflect a shortcoming in the definitions I have found or shortcomings in my reading of the paper rather than an error on their parts.

Hopefully, more research will be forthcoming and it will be possible to better understand the terminology.