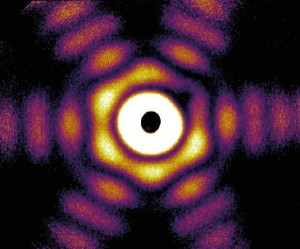

Fig. 1: Nano-fireworks in an argon nanoparticle are ignited by a moderately intense and invisible XUV laser pulse. A subsequent visible laser pulse heats the nanoparticle very efficiently, resulting in its explosion. Electrons and ions move in different directions and send out fluorescence light in various colors. Without the XUV pulse the nanoparticle would remain intact. Courtesy: Max Born Institute in Berlin [Germany]

A team of researchers from the Max Born Institute in Berlin and the University of Rostock demonstrated a new way to turn initially transparent nanoparticles suddenly into strong absorbers for intense laser light and let them explode.

Intense laser pulses can transform transparent material into a plasma that captures energy of the incoming light very efficiently. Scientists from Berlin and Rostock discovered a trick to start and control this process in a way that is so efficient that it could advance methods in nanofabrication and medicine. The light-matter encounter was studied by a team of physicists from the Max Born Institute for Nonlinear Optics and Short Pulse Spectroscopy (MBI) in Berlin and from the Institute of Physics of the University of Rostock [Germany].

A Jan. 19, 2016 MBI press release, which originated the news item, offers more detail,

The researchers studied the interaction of intense near-infrared (NIR) laser pulses with tiny, nanometer-sized particles that contain only a few thousand Argon atoms – so-called atomic nanoclusters. The visible NIR light pulse alone can only generate a plasma if its electromagnetic waves are so strong that they rip individual atoms apart into electrons and ions. The scientists could outsmart this so-called ignition threshold by illuminating the clusters with an additional weak extreme-ultraviolet (XUV) laser pulse that is invisible to the human eye and lasts only a few femtoseconds (a femtosecond is a millionth of a billionth of a second). With this trick the researchers could “switch on” the energy transfer from the near-infrared light to the particle at unexpectedly low NIR intensities and created nano-fireworks, during which electrons, ions and colourful fluorescence light are sent out from the clusters in different directions .. . …

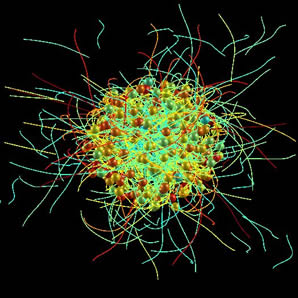

The experiments were carried out at the Max Born Institute at a 12 meter long high-harmonic generation (HHG) beamline. “The observation that argon clusters were strongly ionized even at moderate NIR laser intensities was very surprising”, explains Dr. Bernd Schütte from MBI, who conceived and performed the experiments. “Even though the additional XUV laser pulse is weak, its presence is crucial: without the XUV ignition pulse, the nanoparticles remained unaffected and transparent for the NIR light … .” Theorists around Prof. Thomas Fennel from the University of Rostock modelled the light-matter processes with numerical simulations and uncovered the origin of the observed synergy of the two laser pulses. They found that only a few seed electrons created by the ionizing radiation of the XUV pulse are sufficient to start a process similar to a snow avalanche in the mountains. The seed electrons are heated in the NIR laser light and kick out even more electrons. “In this avalanching process, the number of free electrons in the nanoparticle increases exponentially”, explains Prof. Fennel. “Eventually, the nanoscale plasma in the particles can be heated so strongly that highly charged ions are created.”

The novel concept of starting ionization avalanching with XUV light makes it possible to spatially and temporally control the strong-field ionization of nanoparticles and solids. Using HHG pulses paves the way for monitoring and controlling the ionization of nanoparticles on attosecond time scales, which is incredibly fast. One attosecond compares to a second as one second to the age of the universe. Moreover, the ignition method is expected to be applicable also to dielectric solids. This makes the concept very interesting for applications, in which intense laser pulses are used for the fabrication of nanostructures. By applying XUV pulses, a smaller focus size and therefore a higher precision could be achieved. At the same time, the overall efficiency can be improved, as NIR pulses with a much lower intensity compared to current methods could be used. In this way, novel nanolithography and nanosurgery applications may become possible in the future.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ionization Avalanching in Clusters Ignited by Extreme-Ultraviolet Driven Seed Electrons by Bernd Schütte, Mathias Arbeiter, Alexandre Mermillod-Blondin, Marc J. J. Vrakking, Arnaud Rouzée, and Thomas Fennel.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 033001 – Published 19 January 2016 DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.033001© 2016 American Physical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.