This is an approach to brain-like computing that’s new (to me, anyway). From a January 9, 2018 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

From various magnetic tapes, floppy disks and computer hard disk drives, magnetic materials have been storing our electronic information along with our valuable knowledge and memories for well over half of a century.

In more recent years, the new types [sic] phenomena known as magnetoresistance, which is the tendency of a material to change its electrical resistance when an externally-applied magnetic field or its own magnetization is changed, has found its success in hard disk drive read heads, magnetic field sensors and the rising star in the memory technologies, the magnetoresistive random access memory.

A new discovery, led by researchers at the University of Minnesota, demonstrates the existence of a new kind of magnetoresistance involving topological insulators that could result in improvements in future computing and computer storage. The details of their research are published in the most recent issue of the scientific journal Nature Communications (“Unidirectional spin-Hall and Rashba-Edelstein magnetoresistance in topological insulator-ferromagnet layer heterostructures”).

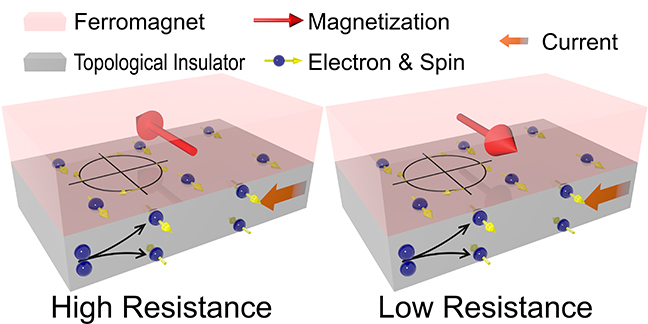

This image illustrates the work,

The schematic figure illustrates the concept and behavior of magnetoresistance. The spins are generated in topological insulators. Those at the interface between ferromagnet and topological insulators interact with the ferromagnet and result in either high or low resistance of the device, depending on the relative directions of magnetization and spins. Credit: University of Minnesota

A January 9, 2018 University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering news release, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

“Our discovery is one missing piece of the puzzle to improve the future of low-power computing and memory for the semiconductor industry, including brain-like computing and chips for robots and 3D magnetic memory,” said University of Minnesota Robert F. Hartmann Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Jian-Ping Wang, director of the Center for Spintronic Materials, Interfaces, and Novel Structures (C-SPIN) based at the University of Minnesota and co-author of the study.

Emerging technology using topological insulators

While magnetic recording still dominates data storage applications, the magnetoresistive random access memory is gradually finding its place in the field of computing memory. From the outside, they are unlike the hard disk drives which have mechanically spinning disks and swinging heads—they are more like any other type of memory. They are chips (solid state) which you’d find being soldered on circuit boards in a computer or mobile device.

Recently, a group of materials called topological insulators has been found to further improve the writing energy efficiency of magnetoresistive random access memory cells in electronics. However, the new device geometry demands a new magnetoresistance phenomenon to accomplish the read function of the memory cell in 3D system and network.

Following the recent discovery of the unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance in a conventional metal bilayer material systems, researchers at the University of Minnesota collaborated with colleagues at Pennsylvania State University and demonstrated for the first time the existence of such magnetoresistance in the topological insulator-ferromagnet bilayers.

The study confirms the existence of such unidirectional magnetoresistance and reveals that the adoption of topological insulators, compared to heavy metals, doubles the magnetoresistance performance at 150 Kelvin (-123.15 Celsius). From an application perspective, this work provides the missing piece of the puzzle to create a proposed 3D and cross-bar type computing and memory device involving topological insulators by adding the previously missing or very inconvenient read functionality.

In addition to Wang, researchers involved in this study include Yang Lv, Delin Zhang and Mahdi Jamali from the University of Minnesota Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and James Kally, Joon Sue Lee and Nitin Samarth from Pennsylvania State University Department of Physics.

This research was funded by the Center for Spintronic Materials, Interfaces and Novel Architectures (C-SPIN) at the University of Minnesota, a Semiconductor Research Corporation program sponsored by the Microelectronics Advanced Research Corp. (MARCO) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Unidirectional spin-Hall and Rashba−Edelstein magnetoresistance in topological insulator-ferromagnet layer heterostructures by Yang Lv, James Kally, Delin Zhang, Joon Sue Lee, Mahdi Jamali, Nitin Samarth, & Jian-Ping Wang. Nature Communications 9, Article number: 111 (2018) doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02491-3 Published online: 09 January 2018

This is an open access paper.