Glasswinged butterfly. Greta oto. Credit: David Tiller/CC BY-SA 3.0

My jaw dropped on seeing this image and I still have trouble believing it’s real. (You can find more image of glasswinged butterflies here in an Cot. 25, 2014 posting on thearkinspace. com and there’s a video further down in the post.)

As for the research, an April 30, 2018 news item on phys.org announces work that could improve eye implants,

Inspired by tiny nanostructures on transparent butterfly wings, engineers at Caltech have developed a synthetic analogue for eye implants that makes them more effective and longer-lasting. A paper about the research was published in Nature Nanotechnology.

An April 30, 2018 California Institute of Technology (CalTech) news release (also on EurekAlert) by Robert Perkins, which originated the news item, goes into more detail,

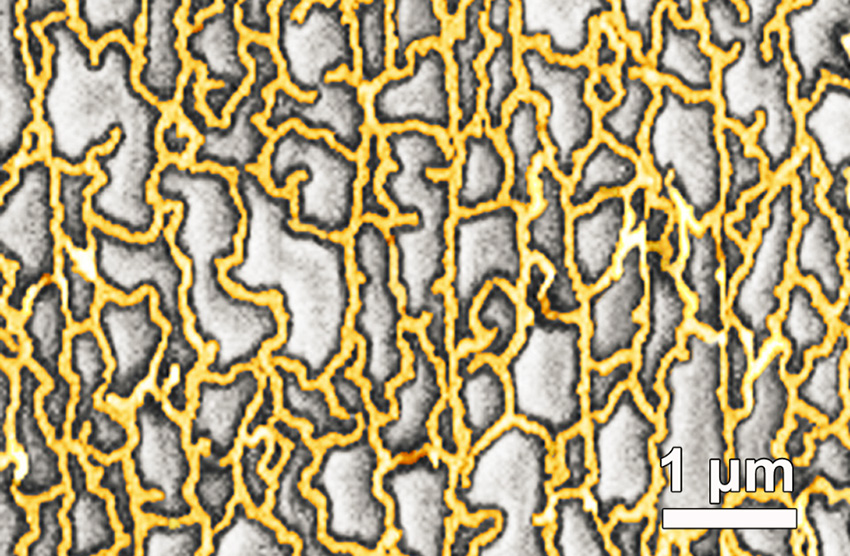

Sections of the wings of a longtail glasswing butterfly are almost perfectly transparent. Three years ago, Caltech postdoctoral researcher Radwanul Hasan Siddique–at the time working on a dissertation involving a glasswing species at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany–discovered the reason why: the see-through sections of the wings are coated in tiny pillars, each about 100 nanometers in diameter and spaced about 150 nanometers apart. The size of these pillars–50 to 100 times smaller than the width of a human hair–gives them unusual optical properties. The pillars redirect the light that strikes the wings so that the rays pass through regardless of the original angle at which they hit the wings. As a result, there is almost no reflection of the light from the wing’s surface.

In effect, the pillars make the wings clearer than if they were made of just plain glass.

That redirection property, known as angle-independent antireflection, attracted the attention of Caltech’s Hyuck Choo. For the last few years Choo has been developing an eye implant that would improve the monitoring of intra-eye pressure in glaucoma patients. Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide. Though the exact mechanism by which the disease damages eyesight is still under study, the leading theory suggests that sudden spikes in the pressure inside the eye damages the optic nerve. Medication can reduce the increased eye pressure and prevent damage, but ideally it must be taken at the first signs of a spike in eye pressure.

“Right now, eye pressure is typically measured just a couple times a year in a doctor’s office. Glaucoma patients need a way to measure their eye pressure easily and regularly,” says Choo, assistant professor of electrical engineering in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science and a Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator.

Choo has developed an eye implant shaped like a tiny drum, the width of a few strands of hair. When inserted into an eye, its surface flexes with increasing eye pressure, narrowing the depth of the cavity inside the drum. That depth can be measured by a handheld reader, giving a direct measurement of how much pressure the implant is under.

One weakness of the implant, however, has been that in order to get an accurate measurement, the optical reader has to be held almost perfectly perpendicular–at an angle of 90 degrees (plus or minus 5 degrees)–with respect to the surface of the implant. At other angles, the reader gives an incorrect measurement.

And that’s where glasswing butterflies come into the picture. Choo reasoned that the angle-independent optical property of the butterflies’ nanopillars could be used to ensure that light would always pass perpendicularly through the implant, making the implant angle-insensitive and providing an accurate reading regardless of how the reader is held.

He enlisted Siddique to work in his lab, and the two, working along with Caltech graduate student Vinayak Narasimhan, figured out a way to stud the eye implant with pillars approximately the same size and shape of those on the butterfly’s wings but made from silicon nitride, an inert compound often used in medical implants. Experimenting with various configurations of the size and placement of the pillars, the researchers were ultimately able to reduce the error in the eye implants’ readings threefold.

“The nanostructures unlock the potential of this implant, making it practical for glaucoma patients to test their own eye pressure every day,” Choo says.

The new surface also lends the implants a long-lasting, nontoxic anti-biofouling property.

In the body, cells tend to latch on to the surface of medical implants and, over time, gum them up. One way to avoid this phenomenon, called biofouling, is to coat medical implants with a chemical that discourages the cells from attaching. The problem is that such coatings eventually wear off.

The nanopillars created by Choo’s team, however, work in a different way. Unlike the butterfly’s nanopillars, the lab-made nanopillars are extremely hydrophilic, meaning that they attract water. Because of this, the implant, once in the eye, is soon encased in a coating of water. Cells slide off instead of gaining a foothold.

“Cells attach to an implant by binding with proteins that are adhered to the implant’s surface. The water, however, prevents those proteins from establishing a strong connection on this surface,” says Narasimhan. Early testing suggests that the nanopillar-equipped implant reduces biofouling tenfold compared to previous designs, thanks to this anti-biofouling property.

Being able to avoid biofouling is useful for any implant regardless of its location in the body. The team plans to explore what other medical implants could benefit from their new nanostructures, which can be inexpensively mass produced.

As if the still image wasn’t enough,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Multifunctional biophotonic nanostructures inspired by the longtail glasswing butterfly for medical devices by Vinayak Narasimhan, Radwanul Hasan Siddique, Jeong Oen Lee, Shailabh Kumar, Blaise Ndjamen, Juan Du, Natalie Hong, David Sretavan, & Hyuck Choo. Nature Nanotechnology (2018) doi:10.1038/s41565-018-0111-5 Published: 30 April 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.

ETA May 25, 2018: I’m obsessed. Here’s one more glasswing image,

Caption: The clear wings make this South-American butterfly hard to see in flight, a succesfull defense mechanism. Credit: Eddy Van 3000 from in Flanders fields – Belgiquistan – United Tribes ov Europe Date: 7 October 2007, 14:35 his file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. [downloaded from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:E3000_-_the_wings-become-windows_butterfly._(by-sa).jpg]