There have been some remarkable advances in the treatment of many diseases, diabetes being one of them. Of course, we can always make things better.and monitoring a diabetic patient’s glucose without have to draw blood is an improvement that may occur sooner rather than later as an April 9,2018 news item on Nanowerk suggests,

Scientists have created a non-invasive, adhesive patch, which promises the measurement of glucose levels through the skin without a finger-prick blood test, potentially removing the need for millions of diabetics to frequently carry out the painful and unpopular tests.

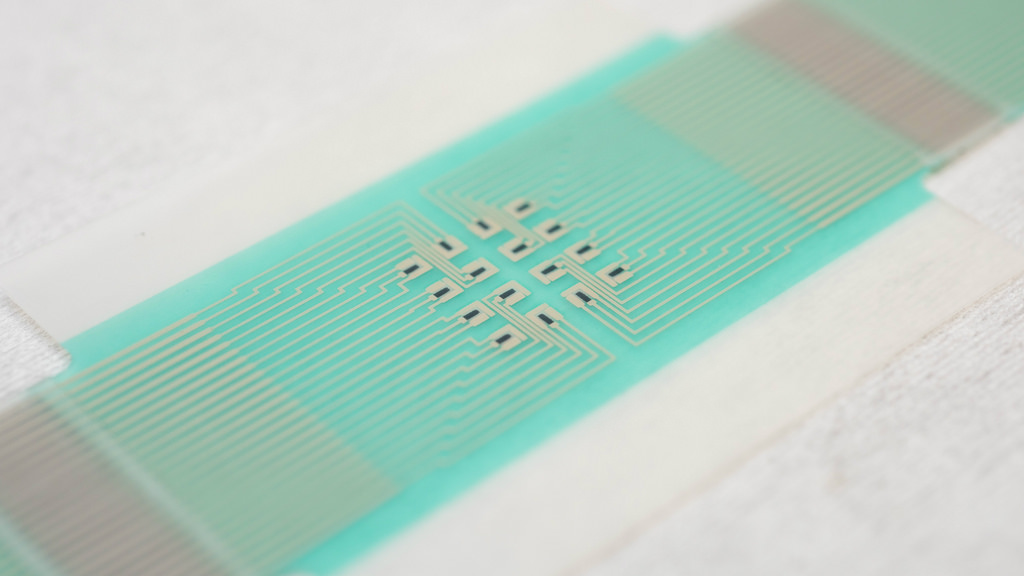

The patch does not pierce the skin, instead it draws glucose out from fluid between cells across hair follicles, which are individually accessed via an array of miniature sensors using a small electric current. The glucose collects in tiny reservoirs and is measured. Readings can be taken every 10 to 15 minutes over several hours.

Crucially, because of the design of the array of sensors and reservoirs, the patch does not require calibration with a blood sample — meaning that finger prick blood tests are unnecessary.

The device can measure glucose levels without piercing the skin Courtesy: University of Bath

An April 9, 2018 University of Bath press release, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

Having established proof of the concept behind the device in a study published in Nature Nanotechnology, the research team from the University of Bath hopes that it can eventually become a low-cost, wearable sensor that sends regular, clinically relevant glucose measurements to the wearer’s phone or smartwatch wirelessly, alerting them when they may need to take action.

An important advantage of this device over others is that each miniature sensor of the array can operate on a small area over an individual hair follicle – this significantly reduces inter- and intra-skin variability in glucose extraction and increases the accuracy of the measurements taken such that calibration via a blood sample is not required.

The project is a multidisciplinary collaboration between scientists from the Departments of Physics, Pharmacy & Pharmacology, and Chemistry at the University of Bath.

Professor Richard Guy, from the Department of Pharmacy & Pharmacology, said: “A non-invasive – that is, needle-less – method to monitor blood sugar has proven a difficult goal to attain. The closest that has been achieved has required either at least a single-point calibration with a classic ‘finger-stick’, or the implantation of a pre-calibrated sensor via a single needle insertion. The monitor developed at Bath promises a truly calibration-free approach, an essential contribution in the fight to combat the ever-increasing global incidence of diabetes.”

Dr Adelina Ilie, from the Department of Physics, said: “The specific architecture of our array permits calibration-free operation, and it has the further benefit of allowing realisation with a variety of materials in combination. We utilised graphene as one of the components as it brings important advantages: specifically, it is strong, conductive, flexible, and potentially low-cost and environmentally friendly. In addition, our design can be implemented using high-throughput fabrication techniques like screen printing, which we hope will ultimately support a disposable, widely affordable device.”

In this study the team tested the patch on both pig skin, where they showed it could accurately track glucose levels across the range seen in diabetic human patients, and on healthy human volunteers, where again the patch was able to track blood sugar variations throughout the day.

The next steps include further refinement of the design of the patch to optimise the number of sensors in the array, to demonstrate full functionality over a 24-hour wear period, and to undertake a number of key clinical trials.

Diabetes is a serious public health problem which is increasing. The World Health Organization predicts the world-wide incidence of diabetes to rise from 171M in 2000 to 366M in 2030. In the UK, just under six per cent of adults have diabetes and the NHS spends around 10% of its budget on diabetes monitoring and treatments. Up to 50% of adults with diabetes are undiagnosed.

An effective, non-invasive way of monitoring blood glucose could both help diabetics, as well as those at risk of developing diabetes, make the right choices to either manage the disease well or reduce their risk of developing the condition. The work was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the Sir Halley Stewart Trust.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Non-invasive, transdermal, path-selective and specific glucose monitoring via a graphene-based platform by Luca Lipani, Bertrand G. R. Dupont, Floriant Doungmene, Frank Marken, Rex M. Tyrrell, Richard H. Guy, & Adelina Ilie. Nature Nanotechnology (2018) doi:10.1038/s41565-018-0112-4 Published online: 09 April 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.