It’s the ‘est’ of it all. The coolest, the whitest, the blackest … Scientists and artists are both pursuing the ‘est’. (More about the pursuit later in this posting.)

In this case, scientists have developed the coolest, whitest paint yet. From an April 16, 2021 news item on Nanowerk,

In an effort to curb global warming, Purdue University engineers have created the whitest paint yet. Coating buildings with this paint may one day cool them off enough to reduce the need for air conditioning, the researchers say.

In October [2020], the team created an ultra-white paint that pushed limits on how white paint can be. Now they’ve outdone that. The newer paint not only is whiter but also can keep surfaces cooler than the formulation that the researchers had previously demonstrated.

“If you were to use this paint to cover a roof area of about 1,000 square feet, we estimate that you could get a cooling power of 10 kilowatts. That’s more powerful than the central air conditioners used by most houses,” said Xiulin Ruan, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering.

…

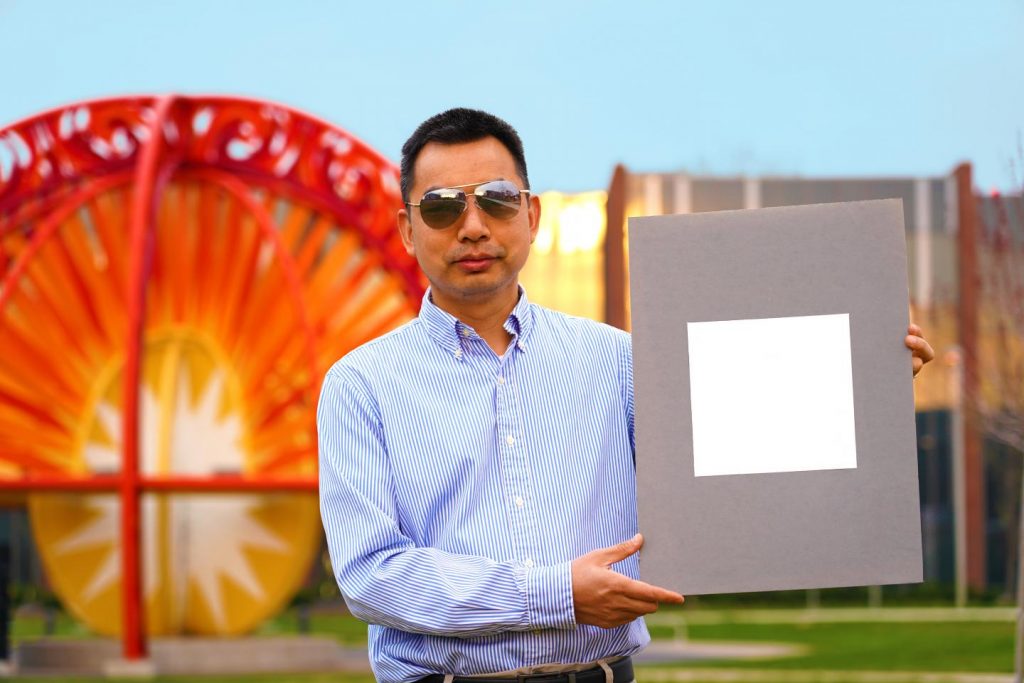

This is nicely done. Researcher Xiulin Ruan is standing close to a structure that could be said to resemble the sun while in shirtsleeves and sunglasses and holding up a sample of his whitest paint in April (not usually a warm month in Indiana).

An April 15, 2021 Purdue University news release (also on EurkeAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail about the work and hints about its commercial applications both civilian and military,

The researchers believe that this white may be the closest equivalent of the blackest black, “Vantablack,” [emphasis mine; see comments later in this post] which absorbs up to 99.9% of visible light. The new whitest paint formulation reflects up to 98.1% of sunlight – compared with the 95.5% of sunlight reflected by the researchers’ previous ultra-white paint – and sends infrared heat away from a surface at the same time.

Typical commercial white paint gets warmer rather than cooler. Paints on the market that are designed to reject heat reflect only 80%-90% of sunlight and can’t make surfaces cooler than their surroundings.

The team’s research paper showing how the paint works publishes Thursday (April 15 [2021]) as the cover of the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

What makes the whitest paint so white

Two features give the paint its extreme whiteness. One is the paint’s very high concentration of a chemical compound called barium sulfate [emphasis mine] which is also used to make photo paper and cosmetics white.

“We looked at various commercial products, basically anything that’s white,” said Xiangyu Li, a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who worked on this project as a Purdue Ph.D. student in Ruan’s lab. “We found that using barium sulfate, you can theoretically make things really, really reflective, which means that they’re really, really white.”

The second feature is that the barium sulfate particles are all different sizes in the paint. How much each particle scatters light depends on its size, so a wider range of particle sizes allows the paint to scatter more of the light spectrum from the sun.

“A high concentration of particles that are also different sizes gives the paint the broadest spectral scattering, which contributes to the highest reflectance,” said Joseph Peoples, a Purdue Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering.

There is a little bit of room to make the paint whiter, but not much without compromising the paint.”Although a higher particle concentration is better for making something white, you can’t increase the concentration too much. The higher the concentration, the easier it is for the paint to break or peel off,” Li said.

How the whitest paint is also the coolest

The paint’s whiteness also means that the paint is the coolest on record. Using high-accuracy temperature reading equipment called thermocouples, the researchers demonstrated outdoors that the paint can keep surfaces 19 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than their ambient surroundings at night. It can also cool surfaces 8 degrees Fahrenheit below their surroundings under strong sunlight during noon hours.

The paint’s solar reflectance is so effective, it even worked in the middle of winter. During an outdoor test with an ambient temperature of 43 degrees Fahrenheit, the paint still managed to lower the sample temperature by 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

This white paint is the result of six years of research building on attempts going back to the 1970s to develop radiative cooling paint as a feasible alternative to traditional air conditioners.

Ruan’s lab had considered over 100 different materials, narrowed them down to 10 and tested about 50 different formulations for each material. Their previous whitest paint was a formulation made of calcium carbonate, an earth-abundant compound commonly found in rocks and seashells.

The researchers showed in their study that like commercial paint, their barium sulfate-based paint can potentially handle outdoor conditions. The technique that the researchers used to create the paint also is compatible with the commercial paint fabrication process.

Patent applications for this paint formulation have been filed through the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization. This research was supported by the Cooling Technologies Research Center at Purdue University and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research [emphasis mine] through the Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (Grant No.427 FA9550-17-1-0368). The research was performed at Purdue’s FLEX Lab and Ray W. Herrick Laboratories and the Birck Nanotechnology Center of Purdue’s Discovery Park.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ultrawhite BaSO4 Paints and Films for Remarkable Daytime Subambient Radiative Cooling by Xiangyu Li, Joseph Peoples, Peiyan Yao, and Xiulin Ruan. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c02368 Publication Date:April 15, 2021 © 2021 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

Vantablack and the ongoing ‘est’ of blackest

Vantablack’s 99.9% light absorption no longer qualifies it for the ‘blackest black’. A newer standard for the ‘blackest black’ was set by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology at 99.99% light absorption with its N.I.S.T. ultra-black in 2019, although that too seems to have been bested.

I have three postings covering the Vantablack and blackest black story,

- The world’s blackest coating material (March 14, 2016 posting) Vantablack was developed in the UK.

- An artistic feud over the blackest black (a coating material) (February 21, 2019 posting) Note: The artists are a little rude to each other

- More of the ‘blackest black’ (December 14, 2019)

The third posting (December 2019) provides a brief summary of the story along with what was the latest from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology. There’s also a little bit about the ‘The Redemption of Vanity’ an art piece demonstrating the blackest black material from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which they state has 99.995% (at least) absorption of light.

From a science perspective, the blackest black would be useful for space exploration.

I am surprised there doesn’t seem to have been an artistic rush to work with the whitest white. That impression may be due to the fact that the feuds get more attention than quiet work.

Dark side to the whitest white?

Andrew Parnell, research fellow in physics and astronomy at the University of Sheffield (UK), mentions a downside to obtaining the material needed to produce this cooling white paint in a June 10, 2021 essay on The Conversation (h/t Fast Company), Note: Links have been removed,

… this whiter-than-white paint has a darker side. The energy required to dig up raw barite ore to produce and process the barium sulphite that makes up nearly 60% of the paint means it has a huge carbon footprint. And using the paint widely would mean a dramatic increase in the mining of barium.

Parnell ends his essay with this (Note: Links have been removed),

Barium sulphite-based paint is just one way to improve the reflectivity of buildings. I’ve spent the last few years researching the colour white in the natural world, from white surfaces to white animals. Animal hairs, feathers and butterfly wings provide different examples of how nature regulates temperature within a structure. Mimicking these natural techniques could help to keep our cities cooler with less cost to the environment.

The wings of one intensely white beetle species called Lepidiota stigma appear a strikingly bright white thanks to nanostructures in their scales, which are very good at scattering incoming light. This natural light-scattering property can be used to design even better paints: for example, by using recycled plastic to create white paint containing similar nanostructures with a far lower carbon footprint. When it comes to taking inspiration from nature, the sky’s the limit.