Plastic waste is of rising concern as researchers report finding it in the Arctic (April 5 2022 ScienceDaily news item), as well as, in human blood (March 25, 2022 article by Margaret Osborne for the Smithsonian Magazine).

This post is highlighting research into how a particular form of plastic degrades in the environment, from an April 27, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily,

Polyethylene, a plastic that is both cheap and easy to process, accounts for nearly one-third of the world’s plastic waste. An interdisciplinary team from the University of Bayreuth has investigated the progressive degradation of polyethylene in the environment for the first time. Although the degradation process leads to fragmentation into ever smaller particles, isolated nanoplastic particles are rarely found in the environment. The reason is that such decay products do not like to remain on their own, but rather attach rapidly to larger colloidal systems that occur naturally in the environment. The researchers have now presented their findings in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

…

An April 25, 2022 Universität Bayreuth press release (also on EurekAlert but published on April 27, 2022), which originated the news item, gives more detail about the research,

Polyethylene is a plastic that occurs in various molecular structures. Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is widely used for packaging everyday consumer goods, such as food, and is one of the most common polymers worldwide as a result of increasing demand. Until now, there have only been estimates as to how this widely used plastic degrades after it enters the environment as waste. A research team from the Collaborative Research Centre “Microplastics” at the University of Bayreuth has now systematically investigated this question for the first time. The scientists developed a novel, technically sophisticated experimental set-up for this purpose. This makes it possible to simulate two well-known and environmentally linked processes of plastic degradation independently in the laboratory: 1.) photo-oxidation, in which the long polyethylene chains gradually break down into smaller, more water-soluble molecules when exposed to light, and 2.) increasing fragmentation due to mechanical stress. On this basis, it was possible to gain detailed insights into the complex physical and chemical processes of LDPE degradation.

The final stage of LDPE degradation is of particular interest for studies addressing the potential impact of polyethylene on the environment. What the researchers discovered was that this degradation does not end with the decomposition of the packaging material released into the environment into many micro- and nanoplastic particles, which have a high degree of crystallinity. The reason is that these tiny particles have a strong tendency to aggregate: they attach rapidly to larger colloidal systems consisting of organic or inorganic molecules and are part of the material cycle in the environment. Examples of such colloidal systems include clay minerals, humic acids, polysaccharides, and biological particles from bacteria and fungi. “This process of aggregation prevents individual nanoparticles created by polyethylene degradation from being freely available in the environment and interacting with animals and plants. However, this is not an ‘all clear’ signal. Larger aggregates that participate in the material cycle in the environment and contain nanoplastics do often get ingested by living organisms. That is how nanoplastics can eventually enter the food chain,” says Teresa Menzel, one of the three lead authors of the new study and a doctoral researcher in the field of polymer materials.

To identify the degradation products formed when polyethylene decomposes, the researchers employed a method that has not been widely used in microplastics research: multi-cross-polarization in solid-state NMR spectroscopy. “This method even allows us to quantify the degradation products yielded by photooxidation,” says co-author Anika Mauel, a doctoral researcher in inorganic chemistry.

Bayreuth’s researchers have also discovered that the degradation and decomposition of polyethylene also leads to the formation of peroxides. “Peroxides have long been suspected of being cytotoxic, meaning they have a toxic effect on living cells. That is another way in which LDPE degradation poses a potential threat to natural ecosystems. These interrelationships need to be studied in more detail in the future,” adds co-author Nora Meides, a doctoral researcher in macromolecular chemistry.

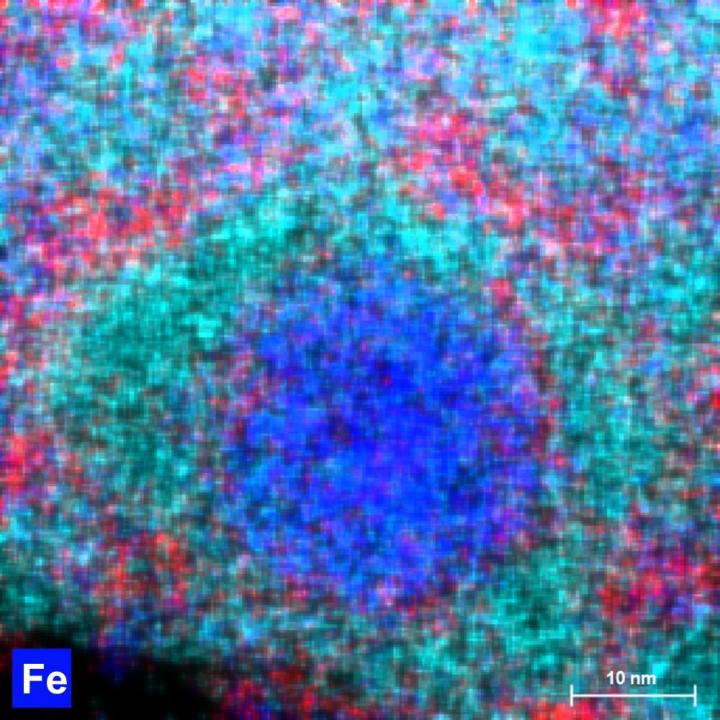

The detailed analysis of the chemical and physical processes involved in the degradation of polyethylene would not have been possible without the interdisciplinary networking and coordinated use of state-of-the-art research technologies on the University of Bayreuth’s campus. In particular, these include scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), NMR spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC).

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Degradation of low-density polyethylene to nanoplastic particles by accelerated weathering by Teresa Menzel Nora Meides, Anika Mauel, Ulrich Mansfeld, Winfried Kretschmer, Meike Kuhn, Eva M.Herzig, Volker Altstädt, Peter Strohrieg, Jürgen Senker, Holger Ruckdäsche. Science of The Total Environment Volume 826, 20 June 2022, 154035 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154035

This paper is behind a paywall.