The Council Canadian of Academies (CCA) released a report on subnational science policy that started life as a workshop on the province of Alberta’s science policy (see my Nov. 10, 2016 posting). Somehow by the time of the April 19, 2017 CCA news release (also received via email and found on EurekAlert) announcing the workshop report, the focus had widened,

A new report, Science Policy: Considerations for Subnational Governments, released today [April 19, 2017] by the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA), affirms the importance of explicit science policies at the subnational level.

“In Canada, science is as much a provincial endeavour as it is a national one,” said Dr. Joy Johnson, FCAHS, Chair of the CCA Workshop Steering Committee, and Vice President of Research at Simon Fraser University. “Currently, the institutions that perform science, together with the infrastructure and funding that enable it, are a part of a multi-level system that is uncoordinated and complex. Realizing the benefits of science as a country requires explicit and effective science policies across all levels of government.”

While all governments have implicit science policies, the report emphasizes that explicit science policies help to articulate the value and objectives of support for science, enhance government coordination and alignment, and increase transparency. Making science policy explicit at the subnational level can also aid in leveraging federal support for science.

The report is the outcome of a two-day expert workshop that sought to identify key considerations for science policies relevant to subnational jurisdictions, specifically for Canadian provinces and territories. Among its findings, the report notes that a comprehensive framework for science policy can be built around five core elements: people, infrastructure, research, science culture, and knowledge mobilization. The report also underscores that science and innovation policies are distinct, but inextricably linked, and that cross-sectoral and cross-governmental coordination and cooperation are essential. With science changing rapidly and research activities becoming increasingly globalized, a commitment to science and to flexible, yet consistent, science policy, is important for long-term success.

“This study suggests that a long-term commitment to subnational science policy is important for maintaining and developing the entire science ecosystem,” said Dr. Eric M. Meslin, FCAHS, President and CEO of the CCA. “Indeed, with the recent release of Canada’s Fundamental Science Review there is now an excellent opportunity for provinces to consider how their own investments in science can be coordinated or aligned with federal priorities for maximum impact.”

Requested by the Government of Alberta, the report also pulls out some specific considerations for the province and highlights successful research initiatives such as the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority (AOSTRA) and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). Overall, the report is intended to be used by Canadian provinces and territories as a roadmap to guide conversations and inform decision-making about science policies at the subnational level.

Is anyone surprised that these experts would advise subnational science policies? Perhaps there’s a naïve ten-year-old out there?

Having gotten that off my chest, I have to admit I wouldn’t have come in with anything too different but I could guarantee a little more humour (assuming I’d have had anything to do with the final report).

On to the report, it’s a solid and workmanlike piece of writing and proposed policy as produced by the participants of the workshop (I see a few more people were added after my Nov. 10, 2016 posting), from the report,

Joy Johnson, FCAHS (Chair of the Steering Committee and Workshop),

Vice President Research, Simon Fraser

University (Burnaby, BC)

Paul Dufour (Steering Committee Member),

Adjunct Professor, Institute for Science, Society and Policy, University

of Ottawa (Gatineau, QC)

Janet Halliwell (Steering Committee Member),

President, J.E. Halliwell Associates Inc. (Salt Spring Island, BC)

Kaye Husbands Fealing (Steering Committee Member),

Chair and Professor, School of Public Policy, Georgia

Institute of Technology (Atlanta, GA)

Marc LePage (Steering Committee Member),

President and CEO, Genome Canada (Ottawa, ON)

Allison Barr, [new]

Director, Office of the Chief Scientist, Ontario

Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science (Toronto, ON)

Eric Cook, [new]

Executive Director and CEO, Research Productivity Council (Fredericton, NB)

Irwin Feller, [new]

Professor Emeritus, Pennsylvania State

University (State College, PA)

Peter Fenwick, [new]

Member, A100 (Calgary, AB)

Richard Hawkins, [new]

Professor, University of Calgary (Calgary, AB)

Jeff Kinder, [new]

Director, Federal Science and Technology Secretariat (Ottawa, ON)

Robert Lamb, [new]

Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Light Source Inc. (Saskatoon, SK)

John Morin, [new]

Director of Policy, Planning and External Relations, Western Economic Diversification Canada

(Edmonton, AB)

Nils Petersen, [new]

Professor Emeritus, University of Alberta

(Edmonton, AB)

Grace Skogstad, [new]

Professor, University of Toronto (Toronto,

ON)

Dan Wicklum, [new]

Chief Executive, Canada’s Oil Sands

Innovation Alliance (COSIA) (Calgary, AB)

And, there were four reviewers,

David Castle,

Vice-President Research, University of Victoria (Victoria, BC)

Timothy I. Meyer,

Chief Operating Officer, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Batavia, Il)

Rémi Quirion, O.C., C.Q., FRSC,

Chief Scientist of Quebec (Montréal, QC)

P. Kim Sturgess, C.C., FCAE,

CEO, WaterSMART Ltd.

(Calgary, AB)

I expect there was an attempt to have women represented in the group of participants and amongst the reviewers. This time it worked out to five women out of 16 workshop participants or approximately 30% and one female reviewer out of four reviewers or 25%. I’m glad to see an effort has been made although I would like to these percentages increase.

As for regional representation, there was none from the North.

The international contingent were all from the US. As I’ve noted with regard to previous CCA reports, the international flavour is garnered from the US, the UK, another commonwealth country such as Australia or New Zealand, and, occasionally, from the European Union. Perhaps one of these times, experts from Asia, South America, or Africa might be included?

The key findings were (from the CCA Science Policy: Considerations for Subnational Governments webpage),

Key Findings

- The rationale for creating an explicit science policy at the subnational level is compelling.

- Science and innovation policies are distinct, but inextricably linked, for all levels of government.

- Subnational governments play many of the same roles as national governments in supporting science.

- A comprehensive framework for a science policy can be built around five core elements: people, infrastructure, research, science culture, and knowledge mobilization.

- Cross-sectoral and cross-governmental coordination and cooperation are central to an effective subnational science policy.

- A subnational science policy can bring clarity to provincial research priorities.

- Committing long term to a subnational science policy is important for maintaining and developing the science system.

I’m picking a few bits out of the report that I found to be of particular interest. The cover features two light bulbs, appropriately since a couple of Canadians invented them (Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans). Then, Thomas Edison bought the patent, refined the invention, and commercialized it. Oddly, I haven’t been able to find any description of or credit for the front page illustration; which would have been helpful as most Canadians are not familiar with that piece of history.

Moving on, there’s no specific definition for the term, subnational.The closest they get is ‘regional’. In Canada, that presumably means provincial although they could be including cities and other regional jurisdictions such as Metro Vancouver, which includes the city of Vancouver along with several other municipalities. However, the impression is that they are discussing provincial governments only.

The emphasis on the provinces is interesting in light of the ‘Naylor’ report (also known as INVESTING IN CANADA’S FUTURE; Strengthening the Foundations of Canadian Research or Canada’s Fundamental Science Review 2017) which found that interprovincial research collaboration was quite poor (see my June 8, 2017 part 2 posting; scroll down about 60% of the way). I did not find any recommendations about improving that situation in the Naylor report and the issue of poor interprovincial collaboration is not mentioned at all in this Science Policy: Considerations for Subnational Governments report.

Moving on to what was in the report that was of interest to me, there was this on computation and digital infrastructure,

Rapid growth in the data requirements of many areas of scientific work is creating both physical and virtual infrastructure needs. Access to high-power computing capacity, data storage, and high-speed networking is increasingly vital to many domains of research activity, from oceanography to neuroscience. In Canada national organizations such as CANARIE and Compute Canada respond to these needs and focus investments in continued development of Canada’s digital research infrastructure (CANARIE, n.d.; CC, n.d.). These may be supported further by provincial investments, such as the Ontario government’s investment in Compute Ontario and the B.C. government’s support for the WestGrid high performance computing network (Gov. of BC, 2011; CC, 2016). Data harmonization, interoperability, and standardization can accelerate research and lead to new advances, particularly in health research. At a pan-Canadian level, the Leadership Council for Digital Infrastructure is seeking to coordinate the diverse players in the digital infrastructure ecosystem (LCDI, n.d.). Subnationally, provinces must also consider the adequacy of regional digital infrastructure, taking into account the requirements associated with provincial research priorities and how best to coordinate provincial, regional, [emphasis mine] and federal support. (p. 11 print; p. 23 PDF)

This was the most specific section of the report naming specific agencies and responsibilities. Intriguingly, they mention provincial and regional support separately but I believe that regional in this instance means ‘Atlantic’, ‘Western’, ‘Prairie’, Maritime’, etc., in other words, provincial and territorial (?) groupings. As the Naylor report also went into some detail about digital infrastructure, which I didn’t choose to mention in my three part commentary, I’m beginning to suspect some anxiety is being felt about data. Given the increasing concerns over cyber security both in Canada and around the globe, the anxiety is to be expected.

Next up, Science Culture (sigh),

Workshop participants suggested that subnational governments have a role to play in supporting a strong science culture through education, public science outreach,

engagement, and communication. This begins with science education at the primary and secondary levels, which provinces can direct through provincial science curricula in the K-12 system. Overall, Canada performs well in student science achievement relative to other countries as measured through the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD, 2016). The development of K-12 science curricula in many provinces benefitted from the 1997 Common Framework of Science Learning Outcomes created by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC, 1997), and from the 1984 Science Council of Canada report, Science for Every Student (SCC, 1984). That report reviewed science education at the primary and secondary levels, and established a vision for public science literacy in Canada. Research has since confirmed the fundamental role of science education as a key determinant of civic science literacy (Miller, 1998).

Support for Informal Science Learning and Engagement

Beyond formal science education, there are many avenues through which subnational governments can support public engagement in the sciences. Science centres and museums provide opportunities for the public to experience science in interactive, hands-on forums, which increasingly harness new digital and communication technologies. Expert science communicators and science ambassadors can make scientific work more accessible to the public, illuminating its relevance and potential. Non-profit organizations can build interest and knowledge among youth in the STEM fields (LTS, n.d.). Science fairs and festivals can also foster excitement about science. Contemporary science festivals often involve collaborations of musicians, artists, [emphasis mine] technologies, engineers, researchers, and communicators of many types.3 Governments can promote scientific and technological awareness through designated science and technology days or weeks. Chief scientists can officially support public science engagement, as is the case in Australia (see Gov. of AU, n.d.). Granting programs can create incentives to encourage researchers to participate in science communication and outreach activities. However, such incentives require careful structuring because not all researchers have the inclination or skills needed to communicate their work to a broader audience.

Subnational governments often support science centres, museums, and other forms of public science outreach. In Quebec, science culture is explicitly identified as a sub-priority in the provincial science policy (Gov. of QC, 2013), but such support is not always connected to or formally recognized in subnational science policies. Leaving such support unconnected to the larger policy framework that outlines the government’s approach to supporting science may contribute to a lack of alignment and coordination of government support. (pp. 12-3 print; pp. 24-5 PDF)

While it can’t be denied that reaching out to children and youth is important, science outreach for adults may be the key to getting more science participation from science and youth. I wrote about two 2012 studies one in the UK (ASPIRES) and the other in the US, which strongly suggested that children and teens can get excited about science and still decide that it’s ‘not for me’ because no one they know (parents, family friends, etc.) has a ‘scientific’ job. The impact that your family has on your occupational aspirations is quite substantive. You can read about the two studies in my Jan. 31, 2012 posting.There’s also a plaintive plea for more adult science outreach in my May 12, 2017 posting. One final note about science culture, given the mention of artists and musicians, I’m surprised they didn’t mention STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts, and mathematics).

The last bit I’m going to mention is Alberta’s position vis-à-vis science policy,

Alberta has a long history of supporting scientific research in the province. As noted earlier, the Alberta Research Council was established in 1921 as Canada’s first provincial research organization (ACT, 2016). Almost 100 years later, its legacy is carried on through research and technology development activities under the auspices of Alberta Innovates. Workshop participants pointed to two sectoral initiatives that are regarded as particular research success stories in the provincial research landscape: the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority (AOSTRA) established in 1974, and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) established through an endowment in 1980 (AIHS, 2016; ACT, n.d.) (see Box 4.1 for a brief discussion of each). Both initiatives are seen as “big bets” that have delivered significant benefits for the province; workshop participants cautioned that small

investments over short periods are less likely to deliver noticeable impacts.

Today, Alberta is home to a dynamic science system and its scientific contributions are nationally and internationally competitive by many measures. Workshop participants identified the talent pool and a strong university research system as key strengths of Alberta’s science system. While bibliometric indicators (indicators based on research publication and citation patterns) are not valid measures of strength across all areas of academic research, they are valuable in many domains, especially when used to compare like with like. Using data collected by the CCA (2012b, 2016) in its studies of the state of science and technology and industrial R&D in Canada, a snapshot of Alberta’s strengths is revealing. Alberta’s research output and impact are broadly on par with Canada’s other large provinces: it has the second highest rate of publications per faculty researcher, the fourth highest Average Relative Citation (ARC) score6 among the provinces, and the third highest rate of doctoral graduates per population after Quebec and Ontario (CCA, 2012b, 2016). Bibliometric analysis indicates that Alberta’s research output is comparatively high in fields such as Public Health and Health Services; Earth and Environmental Sciences; Philosophy and Theology; and Psychology and Cognitive Sciences (Figure 4.1). Fields in which Alberta has a high research impact (as reflected by citations) include Clinical Medicine; Physics and Astronomy; Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; Historical Studies; Economics and Business; and Information and Communication Technologies (Figure 4.2).

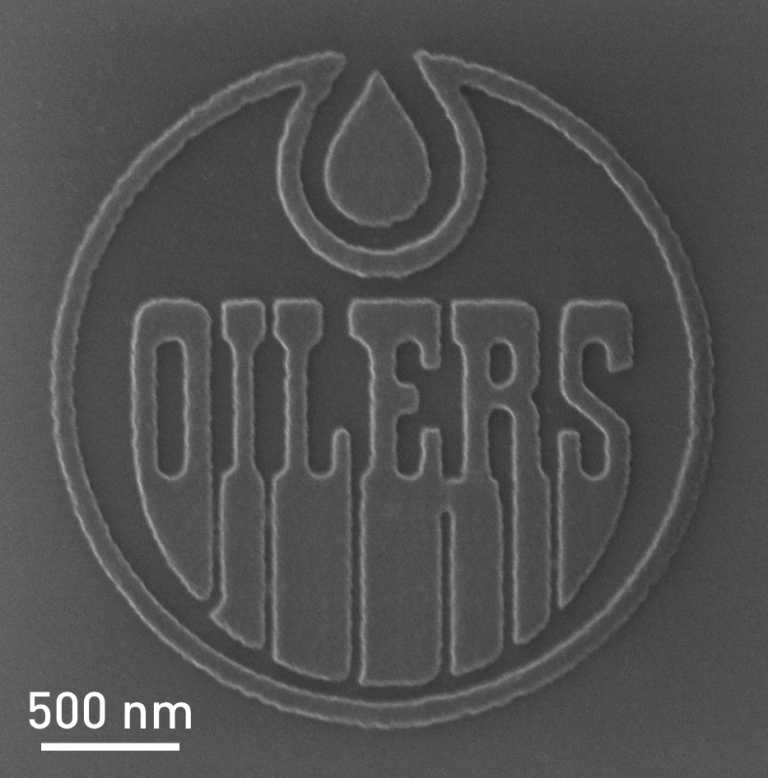

The four themes of Alberta Innovates give a sense of current research priorities, with the government offering significant funding support under bio solutions, energy and environment, health, and technology futures (AI, n.d.). Nanotechnology is another area of focus with the National Institute for Nanotechnology as an important piece of a broader nanotechnology cluster and strategy for Alberta. The province has developed a nanotechnology strategy that seeks to expand the sector, focusing on commercialization, talent, and infrastructure (Gov. of AB, 2007). (p. 20 print; p. 32 PDF)

6 The ARC score “is a measure of the frequency of citation of publications” (CCA, 2012b).

There is no question that Alberta has worked hard to establish its scientific credentials. I’m a little surprised the report doesn’t mention Québec’s efforts in more detail as they have been on a par with Alberta’s. I expect Ontario should also score well this in area but I stumble less frequently on information about Ontario’s science efforts than I do for Alberta and Québec. One last thing, it should be noted that the province of Alberta paid for this workshop/assessment either in large part or in whole.

In sum, they covered the bases competently and thoughtfully if not imaginatively. For anyone who’s has the time, there’s the full report (Science Policy: Considerations for Subnational Governments report) and its recommendations on gender and diversity, researcher mobility, alignment with federal support and programmes, science advice and evidence-based policy, and more.