Light-harvesting devices—I like that better than solar cells or the like but I think that the term serves as a category rather than a name/label for a specific device. Enough musing. A December 17, 2018 news item on Nanowerk describes the latest about graphene and light-harvesting devices (Note: A link has been removed,

An international research team, co-led by a physicist at the University of California, Riverside, has discovered a new mechanism for ultra-efficient charge and energy flow in graphene, opening up opportunities for developing new types of light-harvesting devices.

The researchers fabricated pristine graphene — graphene with no impurities — into different geometric shapes, connecting narrow ribbons and crosses to wide open rectangular regions. They found that when light illuminated constricted areas, such as the region where a narrow ribbon connected two wide regions, they detected a large light-induced current, or photocurrent.

The finding that pristine graphene can very efficiently convert light into electricity could lead to the development of efficient and ultrafast photodetectors — and potentially more efficient solar panels.

A December 14, 2018 University of California at Riverside (UCR) news release by Iqbal Pittalwala (also on EurekAlert but published Dec. 17, 2018), which originated the news item,gives a brief description of graphene while adding context for this research,

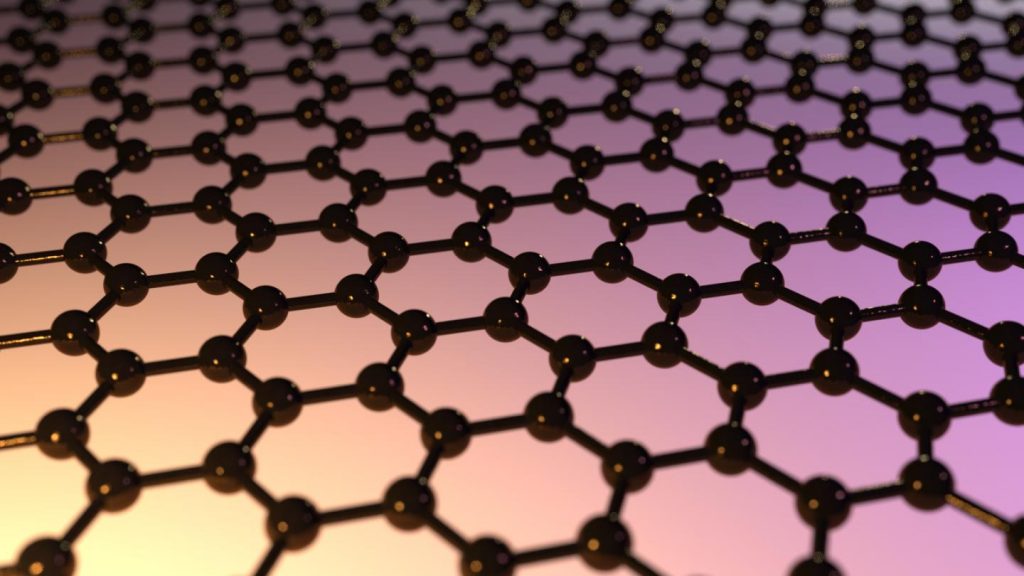

Graphene, a 1-atom thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, has many desirable material properties, such as high current-carrying capacity and thermal conductivity. In principle, graphene can absorb light at any frequency, making it ideal material for infrared and other types of photodetection, with wide applications in bio-sensing, imaging, and night vision.

In most solar energy harvesting devices, a photocurrent arises only in the presence of a junction between two dissimilar materials, such as “p-n” junctions, the boundary between two types of semiconductor materials. The electrical current is generated in the junction region and moves through the distinct regions of the two materials.

“But in graphene, everything changes,” said Nathaniel Gabor, an associate professor of physics at UCR, who co-led the research project. “We found that photocurrents may arise in pristine graphene under a special condition in which the entire sheet of graphene is completely free of excess electronic charge. Generating the photocurrent requires no special junctions and can instead be controlled, surprisingly, by simply cutting and shaping the graphene sheet into unusual configurations, from ladder-like linear arrays of contacts, to narrowly constricted rectangles, to tapered and terraced edges.”

Pristine graphene is completely charge neutral, meaning there is no excess electronic charge in the material. When wired into a device, however, an electronic charge can be introduced by applying a voltage to a nearby metal. This voltage can induce positive charge, negative charge, or perfectly balance negative and positive charges so the graphene sheet is perfectly charge neutral.

“The light-harvesting device we fabricated is only as thick as a single atom,” Gabor said. “We could use it to engineer devices that are semi-transparent. These could be embedded in unusual environments, such as windows, or they could be combined with other more conventional light-harvesting devices to harvest excess energy that is usually not absorbed. Depending on how the edges are cut to shape, the device can give extraordinarily different signals.”

The research team reports this first observation of an entirely new physical mechanism — a photocurrent generated in charge-neutral graphene with no need for p-n junctions — in Nature Nanotechnology today [Dec. 17, 2018].

Previous work by the Gabor lab showed a photocurrent in graphene results from highly excited “hot” charge carriers. When light hits graphene, high-energy electrons relax to form a population of many relatively cooler electrons, Gabor explained, which are subsequently collected as current. Even though graphene is not a semiconductor, this light-induced hot electron population can be used to generate very large currents.

“All of this behavior is due to graphene’s unique electronic structure,” he said. “In this ‘wonder material,’ light energy is efficiently converted into electronic energy, which can subsequently be transported within the material over remarkably long distances.”

He explained that, about a decade ago, pristine graphene was predicted to exhibit very unusual electronic behavior: electrons should behave like a liquid, allowing energy to be transferred through the electronic medium rather than by moving charges around physically.

“But despite this prediction, no photocurrent measurements had been done on pristine graphene devices — until now,” he said.

The new work on pristine graphene shows electronic energy travels great distances in the absence of excess electronic charge.

The research team has found evidence that the new mechanism results in a greatly enhanced photoresponse in the infrared regime with an ultrafast operation speed.

“We plan to further study this effect in a broad range of infrared and other frequencies, and measure its response speed,” said first author Qiong Ma, a postdoctoral associate in physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT.

The researchers have provided an image illustrating their work,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Giant intrinsic photoresponse in pristine graphene by Qiong Ma, Chun Hung Lui, Justin C. W. Song, Yuxuan Lin, Jian Feng Kong, Yuan Cao, Thao H. Dinh, Nityan L. Nair, Wenjing Fang, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Su-Yang Xu, Jing Kong, Tomás Palacios, Nuh Gedik, Nathaniel M. Gabor, & Pablo Jarillo-Herrero. Nature Nanotechnology (2018) Published 17 December 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0323-8

This paper is behind a paywall.