I last wrote about structural color in a Feb.7, 2013 posting featuring a marvelous article on the topic by Cristina Luiggi in the The Scientist. As for cephalopods, one of my favourite postings on the topic is a Feb. 1, 2013 posting which features the giant squid, a newly discovered animal of mythical proportions that appears golden in its native habitat in the deep, deep ocean. Happily, there’s a July 25, 2013 news item on Nanowerk which combines structural color and squid,

Color in living organisms can be formed two ways: pigmentation or anatomical structure. Structural colors arise from the physical interaction of light with biological nanostructures. A wide range of organisms possess this ability, but the biological mechanisms underlying the process have been poorly understood.

Two years ago, an interdisciplinary team from UC Santa Barbara [University of California Santa Barbara a.k.a. UCSB] discovered the mechanism by which a neurotransmitter dramatically changes color in the common market squid, Doryteuthis opalescens. That neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, sets in motion a cascade of events that culminate in the addition of phosphate groups to a family of unique proteins called reflectins. This process allows the proteins to condense, driving the animal’s color-changing process.

The July 25, 2013 UC Santa Barbara news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides a good overview of the team’s work to date and the new work occasioning the news release,

Now the researchers have delved deeper to uncover the mechanism responsible for the dramatic changes in color used by such creatures as squids and octopuses. The findings –– published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, in a paper by molecular biology graduate student and lead author Daniel DeMartini and co-authors Daniel V. Krogstad and Daniel E. Morse –– are featured in the current issue of The Scientist.

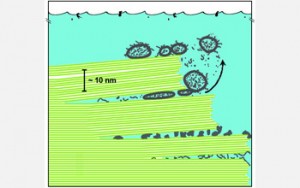

Structural colors rely exclusively on the density and shape of the material rather than its chemical properties. The latest research from the UCSB team shows that specialized cells in the squid skin called iridocytes contain deep pleats or invaginations of the cell membrane extending deep into the body of the cell. This creates layers or lamellae that operate as a tunable Bragg reflector. Bragg reflectors are named after the British father and son team who more than a century ago discovered how periodic structures reflect light in a very regular and predicable manner.

“We know cephalopods use their tunable iridescence for camouflage so that they can control their transparency or in some cases match the background,” said co-author Daniel E. Morse, Wilcox Professor of Biotechnology in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology and director of the Marine Biotechnology Center/Marine Science Institute at UCSB.

“They also use it to create confusing patterns that disrupt visual recognition by a predator and to coordinate interactions, especially mating, where they change from one appearance to another,” he added. “Some of the cuttlefish, for example, can go from bright red, which means stay away, to zebra-striped, which is an invitation for mating.”

The researchers created antibodies to bind specifically to the reflectin proteins, which revealed that the reflectins are located exclusively inside the lamellae formed by the folds in the cell membrane. They showed that the cascade of events culminating in the condensation of the reflectins causes the osmotic pressure inside the lamellae to change drastically due to the expulsion of water, which shrinks and dehydrates the lamellae and reduces their thickness and spacing. The movement of water was demonstrated directly using deuterium-labeled heavy water.

When the acetylcholine neurotransmitter is washed away and the cell can recover, the lamellae imbibe water, rehydrating and allowing them to swell to their original thickness. This reversible dehydration and rehydration, shrinking and swelling, changes the thickness and spacing, which, in turn, changes the wavelength of the light that’s reflected, thus “tuning” the color change over the entire visible spectrum.

“This effect of the condensation on the reflectins simultaneously increases the refractive index inside the lamellae,” explained Morse. “Initially, before the proteins are consolidated, the refractive index –– you can think of it as the density –– inside the lamellae and outside, which is really the outside water environment, is the same. There’s no optical difference so there’s no reflection. But when the proteins consolidate, this increases the refractive index so the contrast between the inside and outside suddenly increases, causing the stack of lamellae to become reflective, while at the same time they dehydrate and shrink, which causes color changes. The animal can control the extent to which this happens –– it can pick the color –– and it’s also reversible. The precision of this tuning by regulating the nanoscale dimensions of the lamellae is amazing.”

Another paper by the same team of researchers, published in Journal of the Royal Society Interface, with optical physicist Amitabh Ghoshal as the lead author, conducted a mathematical analysis of the color change and confirmed that the changes in refractive index perfectly correspond to the measurements made with live cells.

A third paper, in press at Journal of Experimental Biology, reports the team’s discovery that female market squid show a set of stripes that can be brightly activated and may function during mating to allow the female to mimic the appearance of the male, thereby reducing the number of mating encounters and aggressive contacts from males. The most significant finding in this study is the discovery of a pair of stripes that switch from being completely transparent to bright white.

“This is the first time that switchable white cells based on the reflectin proteins have been discovered,” Morse noted. “The facts that these cells are switchable by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, that they contain some of the same reflectin proteins, and that the reflectins are induced to condense to increase the refractive index and trigger the change in reflectance all suggest that they operate by a molecular mechanism fundamentally related to that controlling the tunable color.”

Could these findings one day have practical applications? “In telecommunications we’re moving to more rapid communication carried by light,” said Morse. “We already use optical cables and photonic switches in some of our telecommunications devices. The question is –– and it’s a question at this point –– can we learn from these novel biophotonic mechanisms that have evolved over millions of years of natural selection new approaches to making tunable and switchable photonic materials to more efficiently encode, transmit, and decode information via light?”

In fact, the UCSB researchers are collaborating with Raytheon Vision Systems in Goleta to investigate applications of their discoveries in the development of tunable filters and switchable shutters for infrared cameras. Down the road, there may also be possible applications for synthetic camouflage. [emphasis mine]

There is at least one other research team (the UK’s University of Bristol) considering the camouflage strategies employed cephalopods and, in their case, zebra fish as noted in my May 4, 2012 posting, Camouflage for everyone.

Getting back to cephalopod in hand, here’s an image from the UC Santa Barbara team,

![This shows the diffusion of the neurotransmitter applied to squid skin at upper right, which induces a wave of iridescence traveling to the lower left and progressing from red to blue. Each object in the image is a living cell, 10 microns long; the dark object in the center of each cell is the cell nucleus. [downloaded from http://www.ia.ucsb.edu/pa/display.aspx?pkey=3076]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/CephalopodCamuuflage-300x199.jpeg)

This shows the diffusion of the neurotransmitter applied to squid skin at upper right, which induces a wave of iridescence traveling to the lower left and progressing from red to blue. Each object in the image is a living cell, 10 microns long; the dark object in the center of each cell is the cell nucleus. [downloaded from http://www.ia.ucsb.edu/pa/display.aspx?pkey=3076]

Optical parameters of the tunable Bragg reflectors in squid by Amitabh Ghoshal, Daniel G. DeMartini, Elizabeth Eck, and Daniel E. Morse. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0386 J. R. Soc. Interface 6 August 2013 vol. 10 no. 85 20130386

The Royal Society paper is behind a paywall until August 2014.

Membrane invaginations facilitate reversible water flux driving tunable iridescence in a dynamic biophotonic system by Daniel G. DeMartini, Daniel V. Krogstadb, and Daniel E. Morse. Published online before print January 28, 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217260110

PNAS February 12, 2013 vol. 110 no. 7 2552-2556

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) paper (or the ‘Daniel’ paper as I prefer to think of it) is behind a paywall.