A March 27, 2020 news item on Nanowerk suggests that double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWCNTs) may offer some advantages over single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), NOTE: A link has been removed,

One nanotube could be great for electronics applications, but there’s new evidence that two could be tops.

Rice University engineers already knew that size matters when using single-walled carbon nanotubes for their electrical properties. But until now, nobody had studied how electrons act when confronted with the Russian doll-like structure of multiwalled tubes.

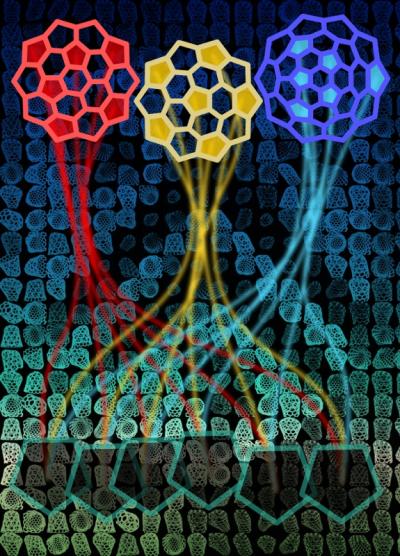

There’s a diagram representing the work,

A March 27, 2020 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further (NOTE: Links have been removed),

The Rice lab of materials theorist Boris Yakobson has now calculated the impact of curvature of semiconducting double-wall carbon nanotubes on their flexoelectric voltage, a measure of electrical imbalance between the nanotube’s inner and outer walls.

This affects how suitable nested nanotube pairs may be for nanoelectronics applications, especially photovoltaics.

The theoretical research by Yakobson’s Brown School of Engineering group appears in the American Chemical Society journal Nano Letters.

In an 2002 study, Yakobson and his Rice colleagues had revealed how charge transfer, the difference between positive and negative poles that allows voltage to exist between one and the other, scales linearly to the curvature of the nanotube wall. The width of the tube dictates curvature, and the lab found that the thinner the nanotube (and thus larger the curvature), the greater the potential voltage.

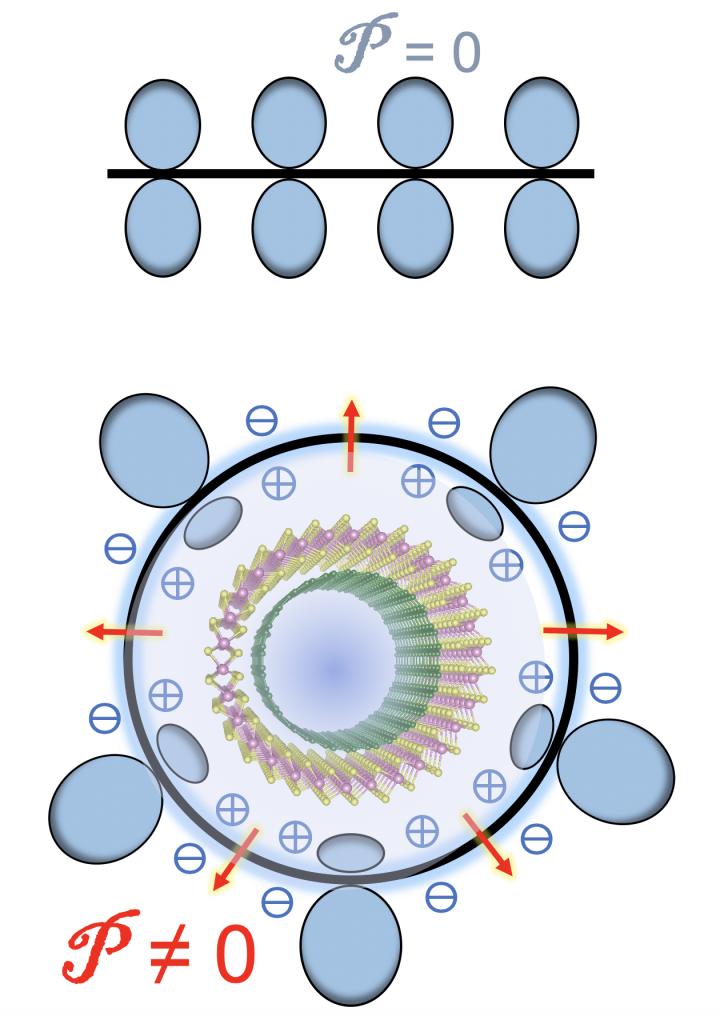

When carbon atoms form flat graphene, the charge density of the atoms on either side of the plane are identical, Yakobson said. Curving the graphene sheet into a tube breaks that symmetry, changing the balance.

That creates a flexoelectric local dipole in the direction of, and proportional to, the curvature, according to the researchers, who noted that the flexoelectricity of 2D carbon “is a remarkable but also fairly subtle effect.”

But more than one wall greatly complicates the balance, altering the distribution of electrons. In double-walled nanotubes, the curvature of the inner and outer tubes differ, giving each a distinct band gap. Additionally, the models showed the flexoelectric voltage of the outer wall shifts the band gap of the inner wall, creating a staggered band alignment in the nested system.

“The novelty is that the inserted tube, the ‘baby’ (inside) matryoshka has all of its quantum energy levels shifted because of the voltage created by exterior nanotube,” Yakobson said. The interplay of different curvatures, he said, causes a straddling-to-staggered band gap transition that takes place at an estimated critical diameter of about 2.4 nanometers.

“This is a huge advantage for solar cells, essentially a prerequisite for separating positive and negative charges to create a current,” Yakobson said. “When light is absorbed, an electron always jumps from the top of an occupied valence band (leaving a ‘plus’ hole behind) to the lowest state of empty conductance band.

“But in a staggered configuration they happen to be in different tubes, or layers,” he said. “The ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ get separated between the tubes and can flow away by generating current in a circuit.”

The team’s calculations also showed that modifying the nanotubes’ surfaces with either positive or negative atoms could create “substantial voltages of either sign” up to three volts. “Although functionalization could strongly perturb the electronic properties of nanotubes, it may be a very powerful way of inducing voltage for certain applications,” the researchers wrote.

The team suggested its findings may apply to other types of nanotubes, including boron nitride and molybdenum disulfide, on their own or as hybrids with carbon nanotubes.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Flexoelectricity and charge separation in carbon nanotubes by Vasilii I. Artyukhov, Sunny Gupta, Alex Kutana, Boris I. Yakobson. Nano Lett. 2020, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b05345 [Online] Publication Date:March 10, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

![[downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nl5017317]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CarbyneMorphs-300x166.gif)