It seems that the second international Nanocar Race (nano Grand Prix) has been bumped from 2021 to 2022. I always find this car race a little challenging to cover. The first race was scheduled for 2016 and then bumped 2017 and, for some reason, I have two posts about the winners of that 2017 race. (sigh) Let’s hope I can manage a little more tidiness this time.

The latest information is from an Oct. 26, 2020 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert),

Nanomechanics at Rice University and the University of Houston are getting ready to rev their engines for the second international Nanocar Race.

While they’ll have to pump the brakes for a bit longer than expected, as the race has been bumped a year to 2022, the Rice-based team is pushing forward with new designs introduced in the American Chemical Society’s Journal of Organic Chemistry.

The work led by chemists James Tour of Rice and Anton Dubrovskiy of the University of Houston-Clear Lake upgrades the cars with wheels of tert-butyl that should help them navigate the course laid out on a surface of gold, with pylons consisting of a few well-placed atoms.

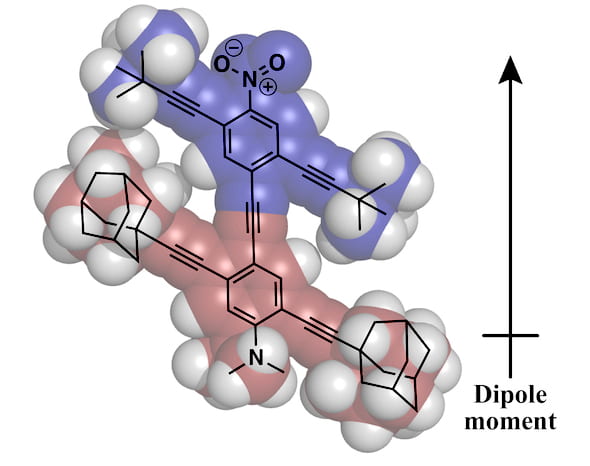

Like their winning entry in 2017’s first international Nanocar Race, these nanocars have permanent dipole moments to increase their speed and drivability on the surface.

“The permanent dipoles make the cars more susceptible to being influenced by electric field gradients, which are used to propel and maneuver them,” Tour said. “It is a feature we introduced for the first competition, and I’m sure many of the entries will now have this advanced design element built into their nanocars.”

This year’s models are also lighter, a little more than the minimum 100 atoms required by new regulations. “The car we used in the first race had only 50 atoms,” Tour said. “So this is a substantial increase in the molecular weight, as required by the updated standards. “It’s likely the race organizers wanted to slow us down since the last time, when we finished the 30-hour race in only 1.5 hours,” he said.

To bring the cars past 100 atoms while streamlining their syntheses, the researchers used a modular process to make five new cars with either all tert-butyl, all adamantyl wheels (as in previous nanocars) or combinations of the two.

At 90 atoms, cars with only butyl wheels, which minimize interactions with the track, and shorter chassis were too small. By using wheel combinations, the Rice lab made nanocars with 114 atoms. “This keeps the weight at a minimum while meeting the race requirements,” Tour said.

The nanocars will again be driven by a team from University of Graz in Austria led by Professor Leonhard Grill. The team brought the Rice vehicle across the finish line in 2017 and has enormous expertise in scanning tunneling microscope-directed manipulations, Tour said. The Grill and Tour groups will meet again in France for the race.

The overarching goal of the competition is to advance the development of nanomachines capable of real work, like carrying molecular-scale cargo and facilitating nano-fabrication.

“This race pushes the limits of molecular nanocar design and methods to control them,” Tour said. “So through this competitive process, worldwide expertise is elevated and the entire field of nanomanipulation is encouraged to progress all the faster.”

The race, originally scheduled for next summer, has been delayed by the pandemic. The racers will still need to gather in France to be overseen by the judges, but all of the teams will control their cars via the internet on tracks under scanning tunneling microscopes in their home labs.

“So the drivers will be together, and the cars and tracks will be dispersed around the world,” Tour said. “But the distance of each track will be identical, to within a few nanometers.”

The Rice-Graz entry won the 2017 race with an asterisk, as its car moved so quickly on the gold surface that it was impossible to capture images for judging. The team was then allowed to race on a silver surface that offered sufficient resistance and finished the 150-nanometer course in 90 minutes.

“The course was supposed to have been only 100 nanometers, but the team was penalized to add an extra 50 nanometers,” Tour said. “Eventually, it was no barrier anyway.” First prize on the gold track went to a Swiss team that finished a 100-nanometer course in six-and-a-half hours.

Tour’s lab built the world’s first single-molecule car in 2005 and it has gone through many iterations since, with the related development of molecular motors that drill through cells to deliver drugs.

Rice graduate student Alexis van Venrooy is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice alumnus Victor García-López and undergraduate John Tianci Li. Dubrovskiy is an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Houston-Clear Lake and an academic visitor at Rice. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of computer science and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanocars with Permanent Dipoles: Preparing for the Second International Nanocar Race by Alexis van Venrooy, Víctor García-López, John Tianci Li, James M. Tour, and Anton V. Dubrovskiy. J. Org. Chem. 2020, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.0c01811 Publication Date:October 21, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

Here’s an image illustrating the ‘car’,

For the curious, there’s my July 9, 2020 posting which announced the second race then scheduled for 2021 and there’s my May 9, 2017 posting, which announced the US-Austrian team winners of the first race..