An Oct. 12, 2016 news item on phys.org announces that Los Alamos National Laboratory (US) may have taken a step towards scaling up quantum dot, solar-powered windows for industrial production (Note: A link has been removed),

In a paper this week for the journal Nature Energy, a Los Alamos National Laboratory research team demonstrates an important step in taking quantum dot, solar-powered windows from the laboratory to the construction site by proving that the technology can be scaled up from palm-sized demonstration models to windows large enough to put in and power a building.

“We are developing solar concentrators that will harvest sunlight from building windows and turn it into electricity, using quantum-dot based luminescent solar concentrators,” said lead scientist Victor Klimov. Klimov leads the Los Alamos Center for Advanced Solar Photophysics (CASP).

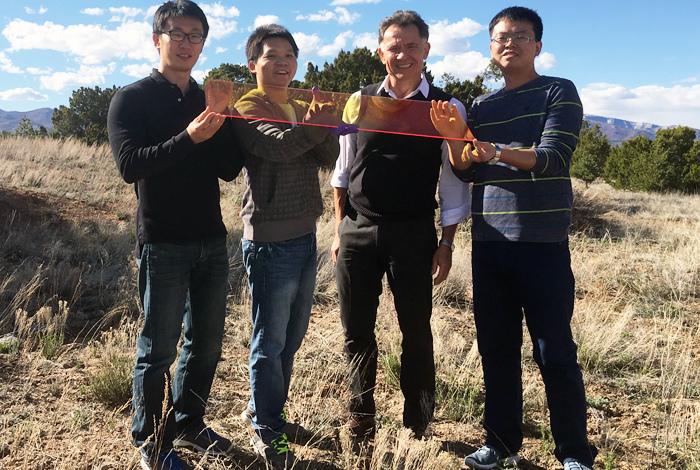

Los Alamos Center for Advanced Solar Photophysics researchers hold a large prototype solar window. From left to right: Jaehoon Lim, Kaifeng Wu, Victor Klimov, Hongbo Li.

An Oct. 11, 2016 Los Alamos National Laboratory news release, which originated the news item, describes the work in more detail,

Luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) are light-management devices that can serve as large-area sunlight collectors for photovoltaic cells. An LSC consists of a slab of transparent glass or plastic impregnated or coated with highly emissive fluorophores. After absorbing solar light shining onto a larger-area face of the slab, LSC fluorophores re-emit photons at a lower energy and these photons are guided by total internal reflection to the device edges where they are collected by photovoltaic cells.

At Los Alamos, researchers expand the options for energy production while minimizing the impact on the environment, supporting the Laboratory mission to strengthen energy security for the nation.

In the Nature Energy paper, the team reports on large LSC windows created using the “doctor-blade” technique for depositing thin layers of a dot/polymer composite on top of commercial large-area glass slabs. The “doctor-blade” technique comes from the world of printing and uses a blade to wipe excess liquid material such as ink from a surface, leaving a thin, highly uniform film behind. “The quantum dots used in LSC devices have been specially designed for the optimal performance as LSC fluorophores and to exhibit good compatibility with the polymer material that holds them on the surface of the window,” Klimov noted.

LSCs use colloidal quantum dots to collect light because they have properties such as widely tunable absorption and emission spectra, nearly 100 percent emission efficiencies, and high photostability (they don’t break down in sunlight).

If the cost of an LSC is much lower than that of a photovoltaic cell of comparable surface area and the LSC efficiency is sufficiently high, then it is possible to considerably reduce the cost of producing solar electricity, Klimov said. “Semitransparent LSCs can also enable new types of devices such as solar or photovoltaic windows that could turn presently passive building facades into power generation units.”

The quantum dots used in this study are semiconductor spheres with a core of one material and a shell of another. Their absorption and emission spectra can be tuned almost independently by varying the size and/or composition of the core and the shell. This allows the emission spectrum to be tuned by the parameters of the dot’s core to below the onset of strong optical absorption, which is itself tuned by the parameters of the dot’s shell. As a result, loss of light due to self-absorption is greatly reduced. “This tunability is the key property of these specially designed quantum dots that allows for record-size, high-performance LSC devices,” Klimov said.

…

The “LSC quantum dots” were synthesized by Jaehoon Lim (a postdoctoral research associate). Hongbo Li (postdoctoral research associate), and Kaifeng Wu (postdoctoral Director’s Fellow) developed the procedures for encapsulating quantum dots into polymer matrices and their deposition onto glass slabs by doctor-blading. Hyung-Jun Song (postdoctoral research associate) fabricated prototypes of complete LSC-solar-cell devices and characterized them.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Doctor-blade deposition of quantum dots onto standard window glass for low-loss large-area luminescent solar concentrators by Hongbo Li, Kaifeng Wu, Jaehoon Lim, Hyung-Jun Song, & Victor I. Klimov. Nature Energy 1, Article number: 16157 (2016) doi:10.1038/nenergy.2016.157 Published online: 10 October 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.